Migration Diplomacy in Ceuta: How a 45-Year-Old Conflict Can Hamper EU Border Management

Posted:

Time to read:

Guest post by Carlota García Barcala. Carlota G. Barcala is a Trainee at the Directorate General Human Rights and Rule of Law (Criminal Law Cooperation Unit) of the Council of Europe. She is currently finishing her MSc in Comparative Criminal Justice at Leiden University. She can be reached by email at 2854805@leidenuniv.nl or through LinkedIn Carlota García Barcala.

‘There are acts that have consequences and they have to be assumed’. With these words, Karima Beinyach, Moroccan Ambassador to Spain, confirmed the suspicions of many academic observers surrounding the humanitarian crisis in Ceuta (Spain), which witnessed the arrival of over 8,000 immigrants in the span of two days (17th/18th May).

Tensions between Madrid and Rabat had previously escalated following Spain’s decision to provide COVID-19 medical treatment to Brahim Ghali, President of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) and secretary-general of the Polisario Front. This guerrilla movement, initially created to counterattack Spanish oppression of African nationalism in the 1970’s, actively opposes Moroccan territorial claims over Western Sahara. Spain’s reception of its ringleader thus led to Morocco’s easing of cross-border security measures, facilitating the irregular entry of thousands of men, women, and minors through land and sea.

This reaction was in line with Moroccan attempts to reinforce its sovereignty over Western Sahara, further bolstered by former President Trump’s recognition of Morocco’s territorial quest in December 2020. The US’s manoeuvre, seeking to increase Israel’s support in the Maghreb, was negatively received in the European Union (EU). Existing tensions, raised by the contested legality of Moroccan exports from occupied Sahrawi lands, were thus heightened.

Over clashing geopolitical interests, migrants have been once more used as an interstate, bargaining chip. The sudden, engineered wave of immigration in Ceuta invites us to revisit the relationship between cross-border mobility management and diplomacy. Can transit countries be considered passive players in border externalisation policies? Is Europe really calling the shots in border management, or have the scales been tipped?

But first, let’s unravel the Western-Sahara conflict.

Western Sahara, located in the north-western African coast, is a former Spanish colony. In 1965, the United Nations urged the colonial government to decolonize the area and hold a referendum on self-determination for the native population (Sahrawis). However, two other countries showed interest in these territories: Morocco and Mauritania. This confrontation ended up before the International Court of Justice, which reaffirmed the Sahrawis’ right to self-determination (1975). Despite this, Spain relinquished control to a joint Moroccan-Mauritanian administration in November 1975, formally abandoning the conflict in 1976.

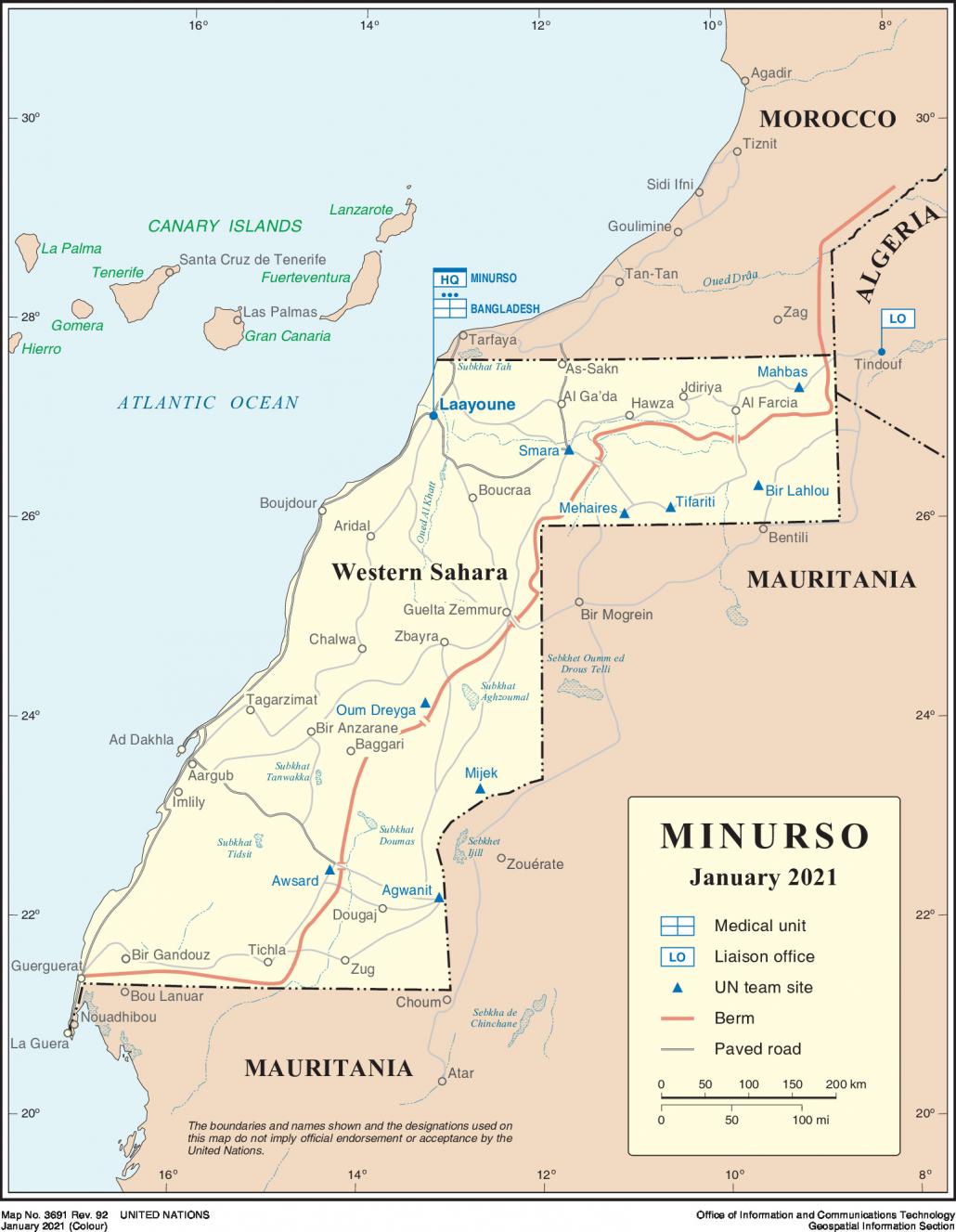

This foreign administration was firmly opposed by the Polisario Front. Military confrontation thus broke between the two sides, with Mauritania ceasing its sovereignty claims in 1978 and Algeria supporting the guerrilla forces (the SADR had eventually been proclaimed from the Polisario’s headquarters in Tindouf). The fight between Moroccan forces and the Polisario Front only deescalated in 1991, with the declaration of a ceasefire and the deployment of a UN mission to organise a referendum (MINURSO).

Forty years later, Western Sahara remains on the UN’s Non-Self-Governing Territories list, with most of its territories illegally occupied by Morocco. Exploitation of its resources (rich in phosphates and fishing banks) has continued with the connivence of the international community, including the EU.

‘There will be more’: the perils of border externalisation

Erdogan’s statement following the opening of the Turkish border in March 2020 (which prompted the arrival of over 10,000 refugees to Greece) illustrates the (political) downsides of EU migration policy. The latter is heavily reliant on ‘border externalisation’ policies. These practices enclose the provision of financial, material (border-management technology) and logistical (police and military patrols) support to bordering countries. These resources are then deployed by ‘transit’ nations to manage migration influxes to Europe (‘host’ countries), thus extending migration control off-shore. The EU-Turkey Declaration in 2016 or the 2017 Italy-Libya Memorandum of Understanding are both good examples of this framework (specifically in response to the Syrian refugee crisis of 2015).

Economic interests aside, Morocco is also a relevant ally to Europe in migration management. Indeed, the events in Ceuta coincided with the granting of a 30 million euros injection by the Spanish government to Rabat for combatting irregular migration, adding up to a 101.7 million budgetary provision to Morocco in the context of the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa (2019). This dependence has become ever more relevant given the increased blockages in the Eastern and Central migration routes (through Turkey and Lybia), which have renewed the importance of the ‘Western Mediterranean’ trail.

Yet, as shown by Erdogan’s words, it would be a mistake to understand these exchanges as a mere imposition of European policy goals. Bordering countries strategically use their geographical position to pursue domestic and diplomatic aims (‘migration diplomacy’). Cooperative (interstate agreements) but also coercive (aggressive, unilateral actions) mechanisms in the field of migration have been de facto deployed by transit nations to press for the lifting of economic sanctions, the emission of official apologies for past colonial rule and the maintenance of anti-democratic governmental reforms. The arrival of thousands of migrants to the Spanish enclave is, as such, only one side of the coin.

Transit countries’ migration diplomacy: the case of Morocco

Beyond its role as a gatekeeper, Morocco, like other traditional transit countries (such as Turkey or Mexico), has gradually become a semipermanent migrant settlement. This new reality can be traced back to increasingly heightened European/Western anti-immigration discourses, which encourage settlement in bordering nations. The Maghrebi state has aligned its migration policy accordingly.

A New Migration Policy was thus introduced in 2013. Based on the principle of socio-economic opportunity, this framework included new legislation on immigration, asylum, and human trafficking, further allowing for the conduction of two regularisation processes. Widely received as an appeasement of migratory pressure by the European block and a response to NGO’s criticisms over human rights violations, researchers highlighted its ulterior, strategic significance towards Sub-Saharan countries. The enhancement of immigrants’ welfare in Moroccan lands was thus linked to the gathering of support for its claim over Western Sahara.

This strategy, together with the analysed events in Ceuta, leads us to the following conclusion: Europe is no longer (if it ever was) omnipotent in controlling its borders. The combination of Ceuta’s engineered migration crisis and the drafting of migrant-friendly legislation passed by King Mohamed VI’s administration reveals Morocco’s agency in dealing with cross-border mobility. What is more, it shows that Europe’s vulnerabilities in the managing of migration (balancing domestic worries and international commitments to migrant’s humans rights) are de facto exploited by transit countries within border externalisation policies, whose leverage in seemingly unrelated diplomatic confrontations is, by these, increased.

Final thoughts

Left unaddressed remain the implications of Ceuta’s show of strength for migrants’ rights. Announced deportations of unaccompanied minors to Morocco last August, heavily criticised by both Spanish NGO’s and international observers, seem to have been, in part, judicially upheld. This situation follows reinforced claims for the redefinition of Spain’s (and Europe’s) migration management choices in the Mediterranean, further agitating the political arena.

With diplomatic relationships between Rabat and Madrid gradually coming back to normal, it remains to be seen what effect this engineered crisis will have in its leitmotiv. Morocco’s demand of Spain’s clear-cut support in the Western Sahara conflict, allegedly in exchange for the latter’s support during the Catalonian crisis, still hangs in the air. In any case, Ceuta’s show of strength will remain as an exemplary repercussion of the country’s agency and of Europe’s vulnerability. This should be a wake-up call for the EU and its Member States to revisit its migration policy choices: if not driven by a solidarity (hardly strengthened by the EU New Pact on Migration and Asylum), at least by political leverage.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style)

García Barcala, C. (2021). Migration Diplomacy in Ceuta: How a 45-Year-Old Conflict Can Hamper EU Border Management. Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2021/10/migration [date]

Share: