‘Stealing the Fire’, 2.0 Style?: Smartphones and Social Media in the Era of Illegalised Mobility

Posted:

Time to read:

Post by Sanja Milivojevic. Sanja is a Senior Lecturer in Criminology at La Trobe, Melbourne, and Associate Director of Border Criminologies. Sanja publishes in English and Serbian on a range of topics, in particular borders and mobility, security technologies, surveillance and crime, gender and victimisation, and international criminal justice and human rights. Her latest book Border Policing and Security Technologies is published by Routledge (2019). This is the fourth installment of Border Criminologies’ themed series on Transforming Borders From Below organised by Marie Segrave and Nancy A. Wonders. The series includes short posts written by international scholars who discuss and develop ideas contained in articles published in a special issue of Theoretical Criminology on Transforming Borders From Below: Theory and Research from across the Globe.

This post is based on my article in the Theoretical Criminology Special Issue: Transforming Borders From Below (and to a lesser extent my monograph Border Policing and Security Technologies: Mobility and Proliferation of Borders in the Western Balkans). Both publications consider the role technology, and in particular smartphones and social media play in enabling safe passage of illegalised border crossers, documenting their journeys, and changing social narratives around mobility. The publications are based on research I conducted in the Western Balkans as one of the main transit routes during what is now known as European migrant ‘crisis.’ The peak of the ‘crisis’ was in 2014-2015, but its impact was felt across Europe and responded to in very different ways.

The article in Theoretical Criminology specifically builds on the work of Stefania Milan, to develop an analysis of the way that men and women on the move transform borders from below. In Ancient Greek mythology, Prometheus stole the fire from the Greek Gods and gave it to the people in order to enable the progress of humankind. Stefania Milan holds that groups and individuals can ‘steal the fire’ from the elites, state agencies and other narrative-setters, by reclaiming technology to convey their own messages. She argues that to do so, groups and individuals need to create autonomous means of communication, innovative platforms that will be immune to gatekeepers’ interventions. I, however, argue that this process largely occurs on existing platforms, such as social media and smartphones.

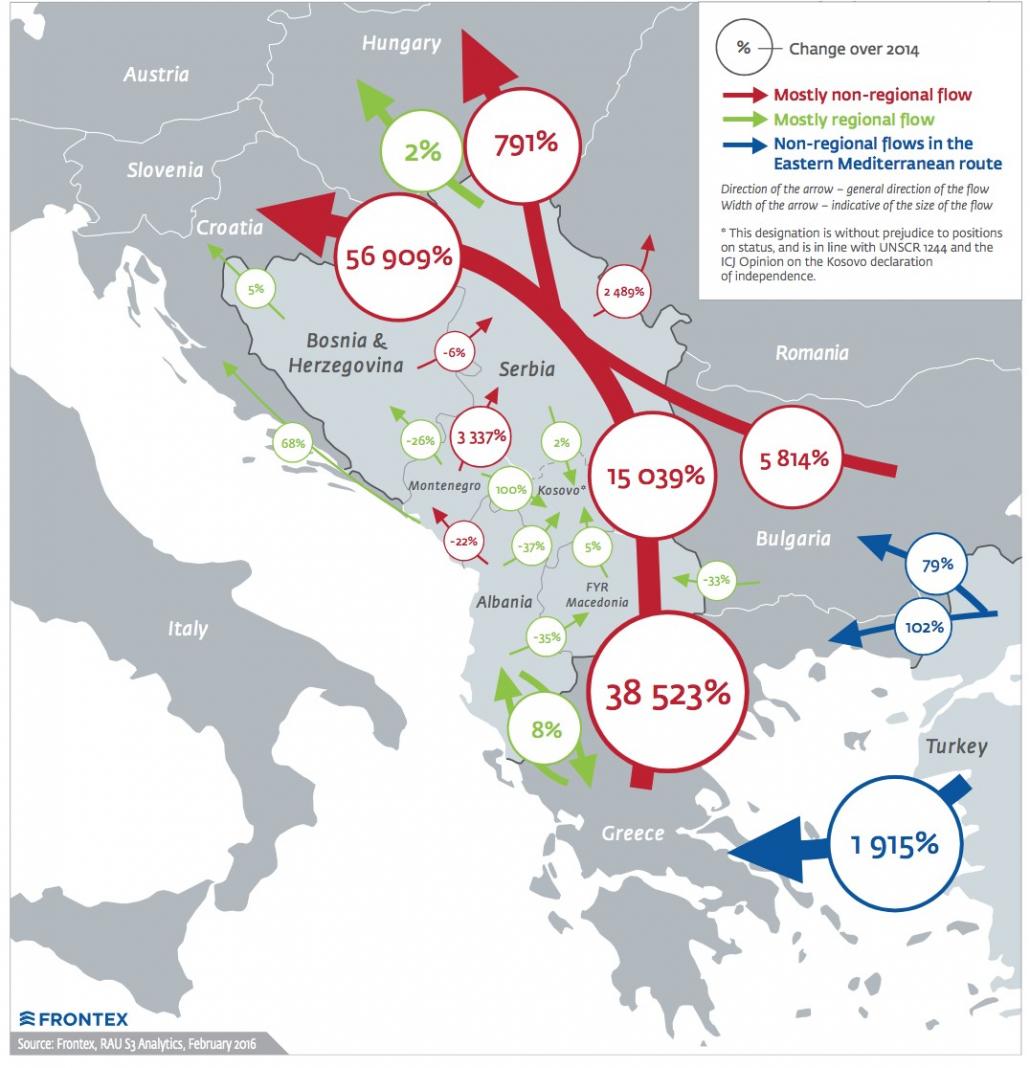

During the ‘crisis', states on the Western Balkans migratory route – especially FYR Macedonia (now called Republic of North Macedonia) and Serbia emerged as buffer zones in which thousands of non-citizens were temporarily housed, immobilised, and then gradually filtered towards Western Europe where they sought asylum and access to labour markets. Faced with some 764,000 people that transited through the region in 2015 (compared to under 45,000 in 2014), nation-states erected fences along territorial borders to counter the mass movement of people. For several months in 2015 the passage was allowed only for citizens of Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq (considered to be ‘genuine’ refugees), only to be followed by the closure of borders in March 2016. Thousands of men, women and children are still stranded in the region. In order to overcome emerging obstacles on their way, they have been relying on mobile technology and social media.

The idea that technology can be used by border regulators to track and govern border crossers has been prominent in public and policy debate for quite some time now. At the same time, technology is increasingly used by border crossers to:

- Enable their migratory projects and limit their reliance on people smugglers;

- Communicate with family and supporters across vast geographical distances;

- Citizen-witness border violence and reach global audience;

- Contribute to border knowledges via digital trail;

- Communicate their stories by recording and transmitting words, images, videos and in doing so “steal the fire” from official truth-tellers (state agencies, media, and supra-national organisations).

Smartphones are, thus, often more important than food or shelter. Staying in touch with family, friends, and smugglers is essential, as a lack of access to information can mean the end of the journey or even death. As my study in the Western Balkans confirms, technology provides more credible migration-related information. Border crossers reclaim technology by crafting unique means of communication in existing digital spaces, and by leaving a digital trail - an active memory of their voyages that serves a variety of purposes.

Digital scrapbooking is an important feature of the journey. ‘Khandan’ from Iran showed me her smartphone with hundreds of photos and videos of her family’s journey through Greece and Macedonia. Featured in the photos and videos were cattle wagons in which they travelled through Greece, places where they rested and hid from police, and other happy and not so happy memories from the 14-hour on-foot trip across Macedonia she took with her children. Importantly, ‘citizen-witnessing’ of border violence can make people feel safer and assist in achieving accountability for human rights violations, as witnessed in the case of Petra László. However, it is not just records of abuses and harms that have the potential to re-humanise the issue: it is experiences, stories of survival, photos of families and friends hugging and smiling, and jokes people share along the way that can challenge the narrative of the ‘dangerous migrant’. Technology can help in this quest; we have seen that in cases of Aylan Kurdi and Omran Daqneesh. Stories and images by border crossers shared on social media have the potential to tell, perhaps even more powerfully, their tales of suffering, pain, survival, and hope.

As technology users, we engage with snippets of information from our networks, and identify what is important to know. We value information, based on where it comes from. Immediacy between the influencer and the social media user, and a number of posts shared by people we trust on social media can potentially have a greater value than the information we access in the traditional media. Emotionally charged reports that originate from those that experience borders, shared by our community of friends and networks on smartphones and social media, can indeed be singled out as more trustworthy and honest account of illegalised migration. In this context, ‘stealing the fire’ means breaking the monopoly of official truth-tellers, through mass self-communication. When border crossers share their photographs and voices in the new digital knowledge commons, they transform bordering strategies, by dismantling the security narratives. Such a quest for social change that will ultimately re-humanise border crossers is even more important given that the ‘crisis’ is far from over. In the book I further these arguments and explore the role security technologies play in both enabling and resisting migratory regimes. Finally, given the lack of attention to the topic in academia, I call for further engagement with technology in border criminologies.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style)

Milivojevic, S. (2019) ‘Stealing the Fire’, 2.0 Style?: Smartphones and Social Media in the Era of Illegalised Mobility. Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2019/05/stealing-the-fire-20 (Accessed [date])

Share: