‘Regreso’: A Film Reframes the Border Spectacle on Unaccompanied Moroccan Minors at the Moroccan-Spanish Border

Posted:

Time to read:

Guest post by Nabil Ferdaoussi. Nabil is a Doctoral Research Fellow at HUMA-Institute for Humanities in Africa (UCT) and Associate Doctoral Fellow at Center for Global Studies (UIR). His research examines forms of post-mortem violence and the politics of race, borders and visuality at the Moroccan-Spanish borderlands.

AGADIR, Morocco—In May 2021, the diplomatic logjam between Morocco and Spain spilled over into an unprecedented border-crossing. More than 10, 000 Moroccan migrants entered Ceuta—including between 2,000 and 3,000 unaccompanied minors. But as the two countries renewed their security collaboration, discussions over the protection of minors and the legitimacy of their deportation took centre stage. Barely concerned with such human rights violations, media reports are laser-focused on the ‘breach’ of Ceuta territory. Since then, clichés of ‘migration crisis’, ‘massive invasions’ and ‘delinquent minors’ have been mobilized by mainstream media to sideline cases of pushback and the eventual deportation of hundreds of Moroccan minors.

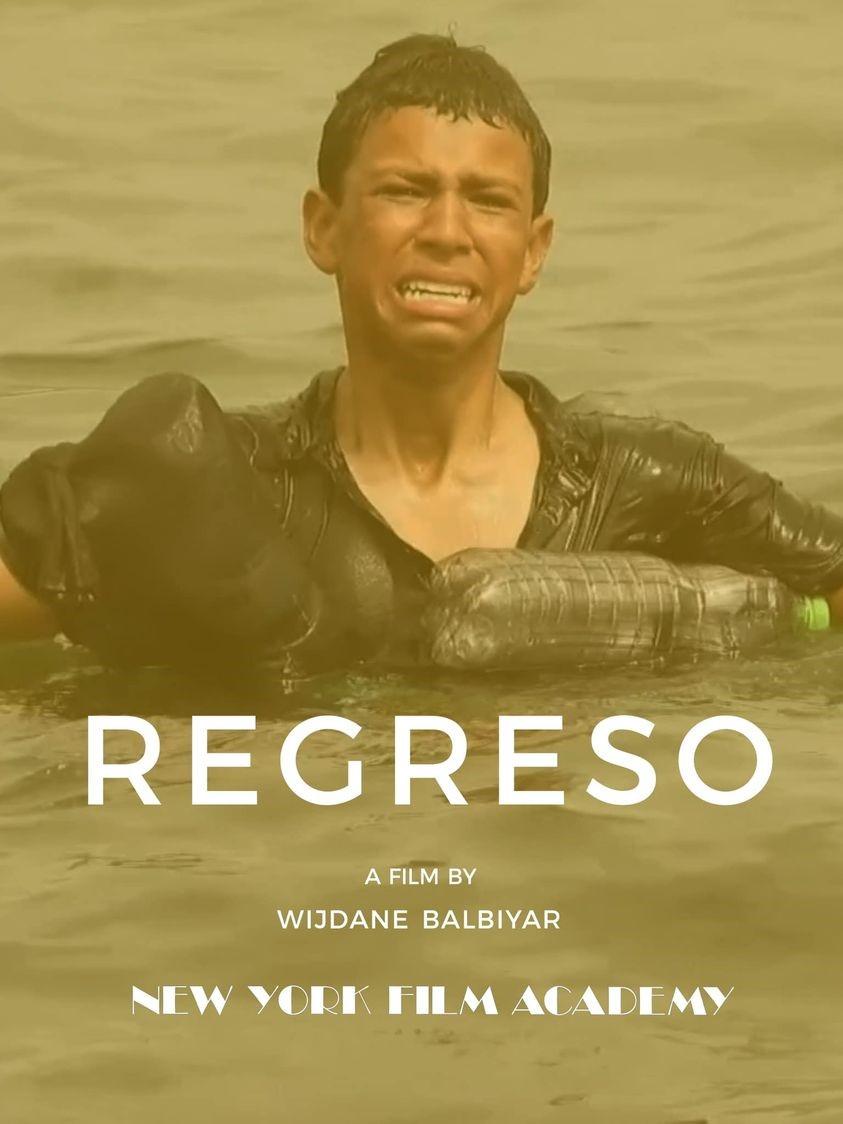

A cascade of press articles, images and footages framed the border-crossing in the parlance of a ‘border spectacle’. Running counter to these visual regimes of immobility, Regreso—a film released in June 2021 by Wijdane Balbiyar—deftly reframes media narratives on the pushback of a Moroccan minor, Achraf Sabir, as he swam his way to the Ceuta shore with empty bottles fastened around his waist. In fact, the release of the documentary film was a jerk-knee response to the border spectacle triggered by an overwhelming video footage that records the pushback of Achraf by a Spanish soldier. The footage is a quintessential portrayal of human flotsam—a wasted life driven by poverty clings to plastic waste to keep afloat.

“Ashraf’s case was in my mind since I saw the video of him swimming his way to Ceuta. I was shocked. I was wondering how I can reach him and tell his story from his own perspective, and what were the reasons that pushed him to risk his life,” the filmmaker stated during our interview.

While media coverage is skewed mostly towards the narratives of governmental officials and the soldier who captured the minor, the film allows us a firsthand narrative of Achraf’s forced return. However, we only grasp Achraf’s precocious despair when we learn more about his past escapades, risking his life on numerous occasions to stow away in Ksar es-Sghir—a small town that borders on Ceuta.

The film quickly redirects our attention from physical borders to socio-economic ones, allowing us an up-close look at his family’s daily battle with poverty in the slum of Hay Errahma in Casablanca. This blatantly belies media narrative that pegs Achraf as an orphan. Equally subverted in the film is the media narrative on Achraf’s forced return by the Spanish soldier who supposedly sympathized with vulnerable minors. “He told me that he would take me to the reception centre to stay with other minors. It was all a lie; he lied to me,”Achraf revealed in the film.

Media misrepresentations promote a culture of immobility. Coupled with the exclusionary practices of border enforcement, visual and narrative regimes of mainstream media enact a border spectacle that oscillates between discourses of securitization and humanitarianism.

“The difference between my film and other journalistic misrepresentations is that I tried to show the real Achraf and the reasons that pushed him to escape,” states Ms. Balbiyar. More sharply in focus, the release of the film coincides with the ongoing debate on the readmission of unaccompanied Moroccan minors in France and Spain. Published last March by the National Assembly, a report on the security issues linked to the presence of unaccompanied minors in France suggests that 10 percent of identified minors—2,000 out of more than 17,000 in 2019— have fallen prey to structural delinquency.

While a number of minors from the Maghreb fall prey to delinquency, a resounding silence surrounds the socio-economic ills behind their mobility. Besides poverty and the search for a better future, family mistreatments, violence and sexual abuse have impelled so many minors to flee their nests in Morocco and join Ceuta last May. The humanitarian organization, Save the Children, informed El País newspaper that 25% of Moroccan minors interviewed in Spain were fleeing physical and sexual violence.

Indeed, some minors were as young as seven or nine, but this should not be capitalized on to justify the illegal deportation of minors who are supposedly needed by their parents. Criminality and vulnerability are the stark antipodes used to justify summary deportations of minors.

Nowhere does the criminalization of Moroccan minors figure more prominently than in elections, particularly in Spain and France. Santiago Abascal, the leader of anti-migrant far-right Vox party in Spain, zealously denounced the number of arrivals, claiming that Morocco was “launching minors like battering rams” against the Spanish borders. By the same token, during the campaign for regional and departmental elections held in June 20 and 27, two candidates from the National Rally formerly National Front) in Yvelines (east of Paris) distributed a leaflet accusing minor migrants of rampant disruption of regional security. Many of these accusations by far-right politicians are used to paper over other serious problems in their country.

Following the ‘border scandal’ in Ceuta last May, there was a heated debate on the reception fatigue in Ceuta, after which the Spanish government was soliciting some of its mainland regions to take on some unaccompanied minors. Spain’s Social Rights Minister, Ione Belarre, informed the Spanish broadcaster TVE that, 'many of them did not know the consequences of crossing the border. And many of them want to go back. So we are working to make that possible'.

Quite recently, as the school entry drew closer in mid-August, Spanish officials resumed the deportation of Moroccan minors under the pretext that the pending custody of minors in Ceuta will affect their education. Such proactive returns of minors, however, are geared towards staving off the burden of ensuring their right to education, as well as the risk of complicating their eventual deportation. What we glean from such a geopolitical scenario, however, is an unprecedented abdication of the EU’s rights-based approach to the right of cross-border mobility, reinvigorating instead its policies of “prevention through deterrence”at its externalized borders. Border enforcement, along with the entire visual and textual gamut of mainstream media, serves to establish the spectacle of border and deepen the architecture of bordering regimes.

Through its aesthetic and reflexive engagement, the documentary caters for a subversive counter-narrative of the border spectacle nourished by mainstream media. It is all the more a modest contribution to the burgeoning subfield of border cinema. Recent films that feature the lived experiences of unaccompanied minors at the Moroccan-Spanish borders—such as The Life Ahead (2020) and Adú (2020), remind us of the repeated violations of children’s rights at the borders.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style)

Ferdaoussi, N. (2021). ‘Regreso’: A Film Reframes the Border Spectacle on Unaccompanied Moroccan Minors at the Moroccan-Spanish Border. Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2021/10/regreso-film [date]

Share: