‘Prepare for a rising surge in insolvencies!’ Or so the predictions went in 2020 when much of the UK (and indeed global) economy shut down as the coronavirus pandemic took hold. But as 2021 draws to a close, still we wonder when—or if—that surge will come. The latest wave of lockdowns in Europe and re-imposition of travel and other restrictions as a result of the Omicron variant raises further uncertainties on corporate growth just as government incentives and monetary intervention are scaled back.

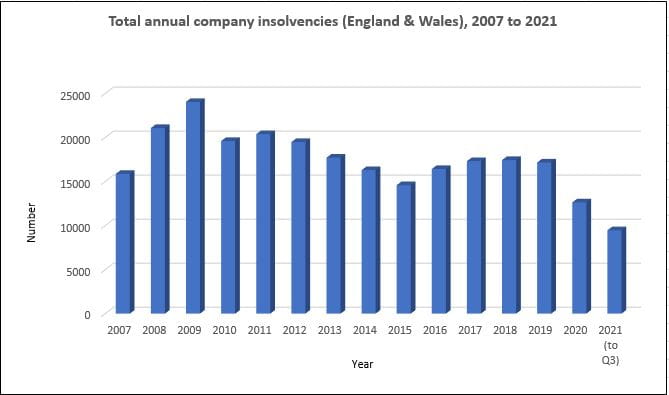

Despite the UK suffering one of its worst financial crises in the last 300 years, restructuring and insolvency activity has been remarkably subdued. Formal company insolvencies in 2020 were at their lowest annual level since 1989 and, while the number is trending upwards, the total number of insolvencies looks set to be similar in 2021. The restructuring market has, for some months now, also been unexpectedly quiet in what was expected to be a much busier period.

Various factors have so far staved off the predicted surge in insolvencies: most notably, the wide-ranging government support measures (including the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme and temporary restrictions on insolvency remedies), free-flowing liquidity from both government coronavirus loan schemes and the corporate debt markets (the latter prompted, in part, by central bank stimulus), and landlord credit from the non-payment of commercial rent. Corporate debt markets are continuing to boom, but with government support measures being withdrawn and economic uncertainty increasing, for how much longer can these benign market conditions continue?

The economic outlook

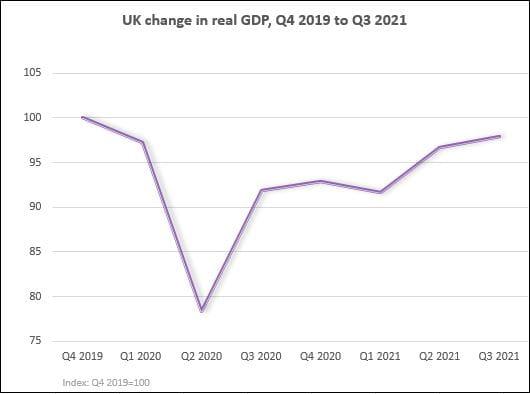

While there are varied predictions for the UK economy, there is growing sentiment that the sharp rebound in economic activity since the end of the first UK lockdown is unstable. The post-pandemic (mostly) V-shaped recovery emerged on the back of rampant demand as the UK economy reopened, with 16.1% GDP growth in Q3 2020 alone. But recent economic figures suggest the economy may be stuttering and the pace of recovery lagging many other major economies. Q3 2021 growth was below expectations and output remained 2.1% below Q4 2019. The latest forecasts may still predict GDP growth of around 5% in 2022 with the economy expected to return to its pre-pandemic size in Q1 2022, but economic headwinds are stiffening.

Source: Based on information and data obtained from ‘GDP First Quarterly Estimate, UK: July to September 2021’ published by the Office for National Statistics on 11 November 2021.

Critical supply-side constraints are weighing most heavily on the economy: supply disruptions, a tight labour market and increasing energy costs are giving rise to concerning inflationary pressures. Add the (so far) negative impact of Brexit on UK trade and the public health uncertainties of the season ahead and it is no wonder many think business and consumer sentiment has peaked. The most pessimistic even suggest that stagflation is on the cards. Whether these downside factors are transitory rather than longer lasting will determine if it is all doom and gloom ahead.

Either way, it appears that 2022 will again be a challenging year for many sectors: construction, manufacturing, travel, hospitality and retail will face particular difficulties but many other industries could equally be added to that list. The energy crisis is showing no signs of letting up with the recent failure of Bulb representing the 25th energy supplier to have exited the market since January 2021, with two other suppliers following the very next day and more failures expected in future weeks. Record energy prices are already having serious knock-on effects on heavy industry, as well as increasing pressure on other cash-tight businesses. If other supply-side constraints continue as expected, many viable businesses could experience working capital strain and be unable to ‘sell their way’ out of trouble even if demand remains high.

So what might this mean for the restructuring and insolvency market in 2022?

We expect the number of formal restructurings to pick up. While the number of restructuring plans to date is lower than the market expected, the resulting case law has been instructive in establishing the restructuring plan as a powerful holistic tool for operational and financial restructurings. And of course, the scheme of arrangement remains an effective tried-and-tested means of implementing balance sheet restructurings. These tools may become increasingly relevant for debt laden companies in lower growth or higher interest or higher cost environments, especially if liquidity starts to dry up. However, these sorts of restructurings are not instant solutions. Some companies must already be facing shortened ‘runways’ to recovery.

Given the suppressed numbers of corporate insolvencies during the pandemic, we also expect a sustained increase in insolvencies though the rate is difficult to predict. The blanket insolvency restrictions were replaced by new tapering measures from 1 October. The recently published Insolvency Service Q3 insolvency statistics show an increase in corporate insolvencies in Q3 2021 (3,765 insolvencies) to the highest number since Q1 2020 and to 90% of the Q3 2019 total. One could say that we’re almost back in the realm of ‘normal’ insolvency figures, but that would ignore the excess number of insolvencies ordinarily expected during a recession and in its immediate aftermath. It should also be noted that the Q3 insolvencies were largely driven by director instigated liquidations (92% of all company insolvencies), likely reflecting natural attrition with directors now being forced to make a call previously delayed as fiscal support and winding-up restrictions taper off.

Source: Based on data obtained from ‘Insolvency Statistics, July to September 2017 (Q3 2017)’ and ‘Quarterly Company Insolvencies by Industry (SIC 2007) (Supplement to the Q3 2021 statistics)’ published by the Insolvency Service.

It won’t be until the end of January 2022, when the Q4 insolvency statistics are published, that we’ll get a better understanding of whether a backlog of creditor petitions held back by the blanket insolvency measures is being cleared and flowing through to an increase in company insolvencies. Even then, though, the number of winding up petitions (and resulting liquidations) will be suppressed by the ongoing restrictions on landlords petitioning for commercial rents and the proposed commercial rent arrears arbitration scheme (see our briefing here). HMRC’s policy intention to take an understanding and supportive approach to tax debts could also have a bearing on the number of petitions we see (HMRC normally being a very significant petitioning creditor).

At the least, we can expect some course correction as the insolvency regime starts to tidy up those unviable businesses which continued operating through the pandemic at the expense of their creditors under cover of the insolvency restrictions. But whether we’ll see increases to the levels seen in 2009 post the global financial crisis—when about 24,000 corporate insolvencies were recorded—remains to be seen. To draw a stark contrast with 2009, there were under 9,500 corporate insolvencies to the end of Q3 2021.

Government support measures, record liquidity and the vaccine rollout might have prevented economic collapse but there is a bumpy ride ahead for industries struggling to get back on an even keel. The expected insolvencies and restructurings may not yet have materialised to the extent the market predicted, but they are not far around the corner.

Giles Boothman is a partner at Ashurst.

Inga West is a counsel at Ashurst.

Andrew Clarke is a senior associate at Ashurst.

Rebecca James is an expertise lawyer at Ashurst.

This post was previously published on Ashurst’s website.

Share: