Motherhood under surveillance: The gendered violence of ICE’s alternatives to detention

The US immigration supervision programme is said to be ‘more humane’, but for Juliana and her children, it means living under constant pressure

Posted:

Time to read:

Guest post by Gabriella Sanchez and Juliana R. S. Gabriella is an independent researcher and consultant. Juliana is the pseudonym chosen by a young Venezuelan woman living in the US, who has lived experience of ICE's Alternatives to Detention Programme.

The arrival of Donald Trump to the White House in January 2025 marked a dramatic, yet not unexpected shift in US migration policy and enforcement. Over the past year, while encounters at the US–Mexico border have fallen sharply, agents for US Immigration and Custom Enforcement (ICE) have apprehended thousands of people across the country, disproportionately targeting racialised communities and relying on excessive use of force. According to the American Immigration Council, by December 2025, nearly 66,000 people were in US immigration detention – the highest level in history. Graphic footage of people being violently dragged by heavily armed and masked individuals out of courthouses, schools, construction sites, churches and supermarkets saturate social media platforms. At least 40 people are known to have died in ICE custody – six of them in the first weeks of 2026 alone.

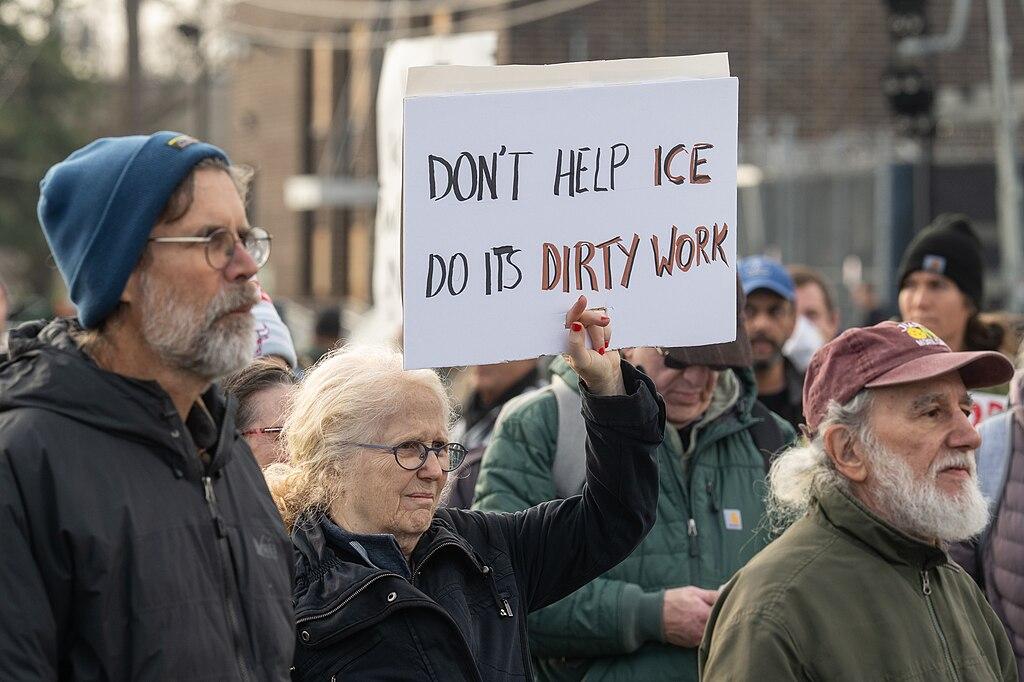

It is imperative to denounce and document the violence being carried out against people and communities across the US. Yet it is also fundamental to pay attention to the lesser-seen experiences of people who, despite having avoided detention, are still subjected to forms of surveillance and control that carry drastic implications on their lives. Alternative practices to detention programmes like electronic monitoring are less spectacular, and thus less likely to be profiled on social media, which, in turn, renders them largely invisible. However, their low-profile does not make them less intrusive, and focusing on their form and impact allows us to understand the complex fabric of the US migration enforcement landscape.

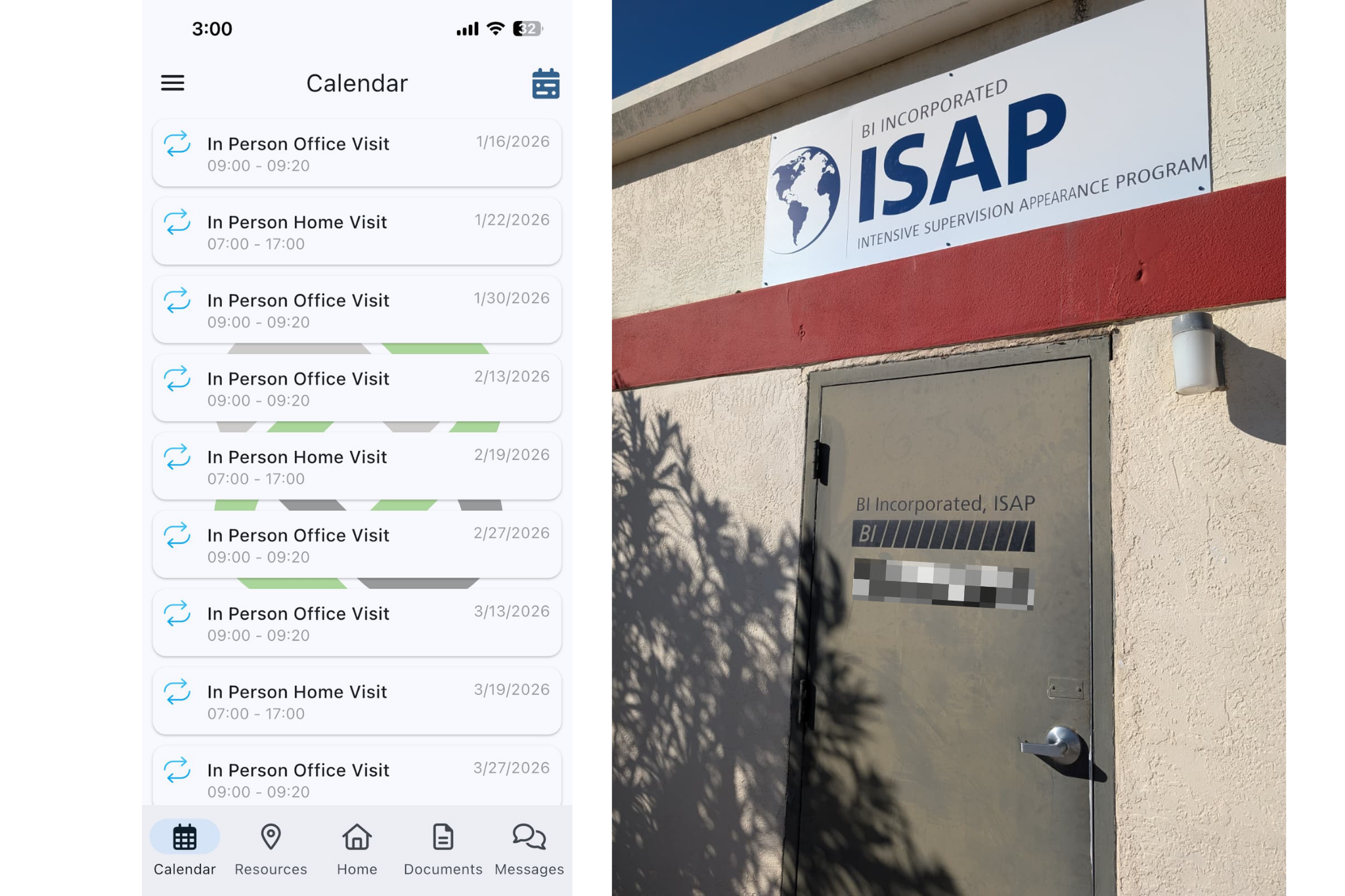

This blog post was co-written with Juliana R. S., the pseudonym chosen by a young Venezuelan woman and mother of two young children. Juliana was admitted into the US in the city of El Paso, Texas, where she has lived since 2024. She was placed under ICE’s alternatives to detention (ATD) program, known locally as ISAP – Intensive Supervision Appearance Program-- upon her arrival. In El Paso, women constitute the majority of those assigned to ATD, which is frequently described by local advocates as “less violent” and “more humane” because it allows women – and specifically, mothers – to be released and care for their children in the community, rather than in detention centres. The gendered aspirations of ISAP have serious implications on the everyday lives of women and their families, as Juliana describes.

Life under surveillance

I entered the United States through El Paso almost two years ago. I am Venezuelan, but was living in Chile when I decided to come to the US to join my husband, who was already here. I travelled with my brother, my daughter, who was four at the time, and my cousin, whose son was only 40 days old when we crossed the Darien. We had planned to apply for entry using the app (CBP One), but after a bad experience with a smuggler in Mexico we got scared, and decided to turn ourselves to US immigration authorities the moment we arrived at the border. After two days of waiting, we were finally allowed to enter the country, and we were immediately placed on ISAP. I was fitted with an ankle monitor. To this day, I must check in with my case manager and with ICE over the phone, and in person, as they request.

A few months after we arrived in El Paso, I became pregnant with my second child. The pregnancy was unexpected and I was very worried, especially knowing how much we had struggled when I first arrived (I had to ask passers-by for help, and for a while we even lacked a place to live). Luckily, I was able to get some prenatal care. My son was born last March. He is a US citizen by birth.

In August 2025, I received an order to attend an immigration court hearing. I was also ordered to bring my children with me. The day of the hearing, the judge dismissed the cases of every single person who had showed up to court, including mine. I had seen what ICE agents were doing to people in other courthouses, and I feared the same thing could happen to me and the kids. When I stepped into the lobby, eight ICE agents were waiting. A female agent called my name. She walked me into an unmarked vehicle. I was really scared. But the agents said they would not keep us in detention, that they just needed to document our arrests, and that afterward they would let us leave.

I know ICE agents are treating people poorly in other places, but the ones who took me in that day treated me well. In fact, one of them waited after the end of his shift to make sure I had a ride to go home. The kids and I were released after a few hours, and I called a friend who is a US citizen who came and picked us up. My husband’s asylum case was dismissed, and he has been under deportation orders for months – for that reason, he cannot accompany me to any of my court hearings, my ICE check-ins, or to the ISAP monitoring visits, since he fears being detained and deported.

I have not received deportation orders, and the government has kept me on ISAP. My friends suspect it is because my baby is a US citizen and so he cannot get deported. But it is a struggle. Each month I must visit both ICE and ISAP. I get scared when I go to the ICE facility – I sometimes fear we will be detained. Last week, of all the people who showed up, my kids and I were pretty much the only ones who were not detained. Another day, an ICE vehicle parked right outside the house. I was coming home from picking up my daughter from school, and I feared they were there to arrest us. I ran and hid in a neighbour’s house until we were certain the agents were gone.

There are also a lot of issues with the ankle monitor. It hurts my skin, and it is heavy. Sometimes it does not charge well, so I also need to carry the charger with me. A couple of weeks ago I got a call from the ISAP office to report immediately. They said my monitor was out of range or not sending a signal, and they thought I had cut it off. Their solution was to tighten it up.

We do not have a car, so I have to rely on public transport. The bus takes about one hour each way to the ISAP office. My son has had a lingering cold and fever for a few months now. I think it is because we have to leave very early in the morning to be at the ISAP office on time, and the winter has been really harsh. In early January he ended up in the emergency room because his fever would not go down.

The frequency of the monitoring also affects my daughter. There are weeks when she misses two or three days of school because of the appointments. The clerks at her school are very difficult to deal with. She has missed so many days of school, the school has threatened to put her on academic probation, or to report me to the authorities for child neglect. Once, I provided documentation to get the absences related to our ISAP and ICE visits excused, and yet the school claimed they had not received it. The ISAP counsellor finally told me this last visit that I no longer have to bring my daughter to the check-ins. But she still needs to come with me to the ICE appointments. (While to our knowledge children are not mandated to be present for ICE check-ins, agents are known to reprimand and even detain mothers for not bringing their children with them to their appointments).

I am waiting to hear about the next stage of my case. I have not received any updates, not to mention the immigration policies towards Venezuelans keep changing. We do not know what will happen to us. When Maduro was taken, we were excited. But that was short lived, because his men are still in control. And while everyone is concerned about the oil, the truth is that people are struggling right now, and all that matters to me is whether my parents will have enough food to survive.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or find us on LinkedIn and Bluesky.

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style):

J. R. S. and G. Sanchez. (2026) Motherhood under surveillance: The gendered violence of ICE’s alternatives to detention. Available at:https://blogs.law.ox.ac.uk/border-criminologies-blog/blog-post/2026/01/motherhood-under-surveillance-gendered-violence-ices. Accessed on: 04/03/2026Keywords:

Share: