Violent Ties: Kinship, Migration, and the Continuity of Reproductive Injustice for Central American Women

Posted:

Time to read:

Guest post by Dr. Miranda Cady Hallet and Rebecca Judeh. Miranda is an Associate Professor of Anthropology, Human Rights Center Research Fellow, and Associate Director of Human Rights Studies Program at the University of Dayton. She is a legal anthropologist with over 20 years of experience working with transnational migrant communities, particularly from El Salvador, and conducting research on the relationships between these communities and systems of law and law enforcement. Rebecca is a PhD student in Sociology at FCSH, Nova University Lisbon and has a background in immigration law.

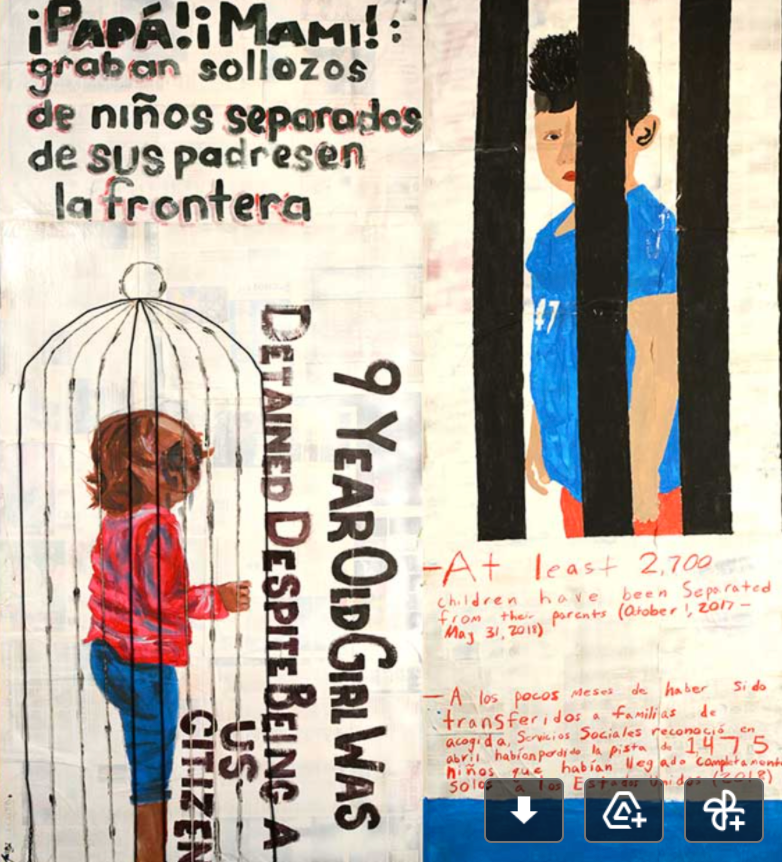

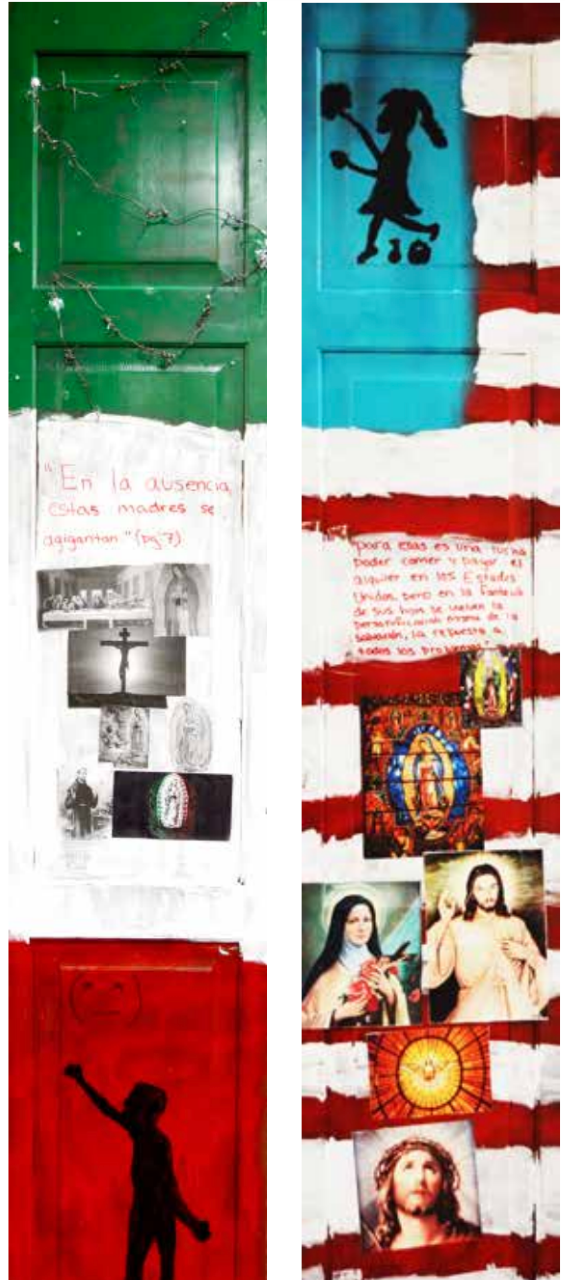

ARTWORK PROTESTING FAMILY SEPARATION CREATED BY STUDENT ARTISTS FROM THE "BORDER DOORS" PROJECT FACILITATED BY DR. CLAUDIO PEREZ OF SANDIA PREPARATORY SCHOOL IN ALBUQUERQUE, NEW MEXICO. FROM LEFT TO RIGHT, THESE IMAGES WERE CREATED BY U.T. NGUYEN AND TANNER BOLLINGER.

Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador have come to occupy a notorious reputation as some of the most violent countries in the Americas. Gendered violence in this part of the world rose significantly in the 21st century, with sexual assaults and femicides increasing at a rate outstripping the growth of murder and assault in general. Such intimate harms– systemic and traumatizing– have been exacerbated by the pandemic, especially in countries with draconian lockdowns like El Salvador.

In addition to suffering bodily violence, many Central American women experience forms of reproductive injustice and attacks on kinship ties, contributing to their displacement. Women flee because of assaults on relationships: whether pressured into early marriage, shamed for pregnancy, criminalized for miscarriage, or threatened by a partner who promises to take the kids. The ways police and other authorities enable such patriarchal aggression highlights collusion between state and gendered violence, documented by expert witnesses in asylum hearings as well as in ethnographic work.

As women are driven into mobility by these abuses, they continue to face similar forms of violence, control, and marginalization throughout their journeys; challenging their right to agency over their family ties and their intimate lives. In the U.S., migrant women and their families are typically apprehended at the border, sometimes separated from their companions– even close kin– and detained. The intensive use of incarceration as deterrence against women and children expanded under both Obama and Trump. The work of Sara Riva and others documents the harsh and inhumane conditions families face, especially under pandemic conditions, as well as the ways border enforcement contributes to the dehumanization of migrants.

The infamous “Zero Tolerance” policy introduced in 2018, leading to the seizure of thousands of children by the U.S. government, intensified this criminalization of Central American mothers and further weaponized institutions and discourses of protection against them. While male migrants were often depicted as criminals via stereotypes of drug traffickers and rapists throughout the Trump Administration, women in this instance were framed as criminally bad mothers, possibly “trafficking” their own children.

Echoing the actions of abusers who threaten to “take the children away,” this policy not only used the separation of kin as a strategy of deterrence, but in the end, predictably violated women’s reproductive rights. The family separation policy placed migrant families in the middle of violent systems, forcing women to make impossible tradeoffs between kinship ties and safety.

Impacted by these and other repressive policies, the experiences of Central American migrant women in the denominated “safe country” replicate the traumatic violence, gendered harms, and reproductive injustices that initially drove them from their homes. Anthropologist Shannon Speed has compellingly argued that this violence disproportionately impacts poor and indigenous women, revealing how policies that are race and gender-neutral on their face can nonetheless operate to target marginalized people.

It is worth noting that the spectacle of child separation that so briefly captured media attention in the summer of 2018 is not exceptional, but merely an extreme manifestation of continuous forms of state violence against Central American migrants and their kin, as well as more broadly against illegalized and mixed-status families. Throughout U.S. history, racialized communities in the U.S. national territory have been subjected to intrusive policies, such as forced sterilization, which undermine kinship and reproductive rights. Two infamous examples of such violence are the forced attendance of Native American children at residential boarding schools that criminalized cultural expression, language, and contact with family, as well as the internment of Japanese-American families during World War II.

Contemporary immigration policy replicates this form of “multigenerational punishment” by frequently imposing the separation of families, terminating kinship rights, eliminating domestic and gender-based asylum, or otherwise threatening the integrity and safety of migrants and their families– not only at the U.S.-Mexico border but throughout what some scholars are calling Mexico’s “vertical border.” Our current research project documenting these continuities contributes to the broader scholarly evidence on what Cecilia Menjívar and Leisy Abrego have termed legal violence– the cumulative harm suffered by migrant families due to policy.

Even women who are able to enter the U.S. with their children may find that their kinship and reproductive rights are at risk later on– for example, deportation itself often splits up mixed-status families, and migrant parents are disproportionately more likely to face custody challenges. One such case is the situation of Sara (Sarita) Mendez-Morales, an indigenous woman and mother from Guatemala who was detained for years in isolated jails in Ohio. Her initial displacement was related to many factors, including the ways she was forced to work from an early age, sexually abused as a young teenager, and rejected and evicted when she became pregnant. She migrated to the U.S. and lived as a single mother for some time, and then moved in with a man who eventually began to sexually abuse her daughter.

Due to language barriers and institutional negligence, when she reported her partner’s abuse, Sarita found herself accused of child endangerment. Her lawyer, unaware of the immigration consequences, advised her to plead guilty. Although U.S. law requires lawyers to inform their clients of such risks, many criminal defense lawyers lack this expertise. To make matters worse, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) used their discretion to keep her incarcerated after she served time for the guilty plea--for over two years as she went through two immigration hearings, winning humanitarian relief both times. Yet as a result of her time in detention and criminal plea, Sarita lost most parental rights including custody of her daughters.

Sarita’s story prompts us to recognize the continuities of gendered and state violence for Central American migrant women– even after they flee. At the same time, such experiences call our attention to the intimate dimensions of politics and the integral role of kinship in relations of power. By acknowledging these, we have a chance to confront the ways systems of migration control reproduce violent mechanisms of intimate gendered and racialized repression.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style)

Hallet, M. C. and Judeh, R. (2022) Violent Ties: Kinship, Migration, and the Continuity of Reproductive Injustice for Central American Women. Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2022/05/violent-ties [date]

Share: