Re-Bordering Policies and De-Bordering Practices in Pandemic Times: Offshore Isolation As De Facto Detention

Posted:

Time to read:

Guest post by Chiara Denaro. Chiara is a Postdoctoral researcher in Sociology at Trento University on the project “PRIN-2017, Debordering activities and citizenship from below of asylum seekers in Italy”. She is a social worker and legal expert, working with migrants and refugees. Her socio-legal research work concerns asylum and migration policies in the Mediterranean space, border control policies, human rights, right to asylum, as well as the practices and strategies of resistance put in place by people on the move. As part of WatchTheMed Alarm Phone, Chiara focuses on the Central Mediterranean route.

The spread of the Covid-19 pandemic, more appropriately defined by Horton as a syndemic, deeply affected human mobilities worldwide, by challenging the actual configuration of border regimes. In particular it led to the introduction of further restrictions on freedom of movement, by hindering access to safe and legal pathways for those in need of protection, and exacerbating existing vulnerabilities. Migrants were depicted by the media as a public health risk, potential carriers and spreaders of COVID-19, and quarantine and lockdown strategies operated along axes of structural inequality, such as gender, race and citizenship. Tazzioli’s concept of ‘hygienic-sanitary borders’, helps to highlight states’ attempts to instrumentalize the pandemic related health risks to further containing human mobilities as well as preventing access to rights, according to the logic of ‘confining to protect’.

Dating back to the 1800 with the famous Quarantine Island, the resort to offshore quarantine measures to deal with the Covid-19 pandemic has been observed worldwide. For example, Australia’s initial response to the health crisis included the transfer of foreign citizens, including Chinese Australians, to the offshore Christmas Island prison. Against the increased replication of the Australian model of offshore processing of asylum seekers on islands (i.e. Nauru, Manus Island) in the eastern European context (i.e. Greek Islands), several scholars and NGOs have underlined the serious repercussions of those policies both in terms of human rights violations and of mental health issues, often culminated in suicide attempts. At the beginning of April 2020, both Italy and Malta declared their harbours as ‘unsafe’ for people rescued at sea, by increasing the rescue gap in the central Mediterranean and providing the (il)legal ground for the implementation of offshore isolation measures, onboard of tourist ships, resulting in a de facto detention.

Drawing on in-depth interviews with institutional and non-governmental stakeholders implementing extraterritorial quarantine measures, as well as with experts and migrants, in this post, I will provide an overview of the re-bordering measures enacted by the Italian government to limit territorial access to seaborne migrants, in order to prevent the diffusion of Covid-19, and explore the impact of the “offshore detention system”. I will also shed light on resistance against such restrictions from migrants and civil society, as a matter of de-bordering.

In Italy, Joint Ministerial decree which defined Italian harbours as being partially unsafe, was followed by a Head of Civil Protection decree which decided the establishment of ‘quarantine ships’. Despite this measure being initially only for those who were rescued outside national waters, by non-Italian flagged vessels, and outside the Italian Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre (IMRCC), it was de facto extended to all newly arrived persons. According to data collected by ASGI, in the frame of In Limine project, more than 13.500 people passed through this system during the first year (April 2020-2021), including more than 1.000 unaccompanied minors, none of whom had access to the asylum procedure. In October 2020, the Italian offshore isolation system started being used also to detain asylum seekers who had been in Italy for years.

After one month, due to NGO protests, and appeals by their lawyers - aimed at highlighting both its discriminatory nature as well as the possible illegitimate consequences of the measure itself, which effectively turned asylum seekers into irregular migrants – this praxis was suspended. In the summer of 2021, after more than one year from their launch, the Italian “quarantine ships” are still operational and migrants who are transferred onto these ships are still protagonists of various kinds of protests, against their de facto detention onboard. One of the most recent ones took place just few days ago, on 26 August, after the transfer of 77 people onto Allegra ship, which was anchored at Augusta harbour. Some people attempted to escape, even by jumping overboard and risking their lives, reportedly because they had already spent a quarantine period in a reception centre on land, located the province of Agrigento.

Kriesi et al.’s concept of ‘external re-bordering’ – as a multidimensional whole of measures adopted by frontline EU states to reinforce existing border infrastructures, looks particularly useful to keep together the various components of the EU border regime – such as externalization policies, Search and Rescue policies, asylum policies, reception and detention policies of asylum seekers – which were affected by pandemic related measures. The ‘closed harbour strategy’ was turned into an ‘unsafe harbour strategy’, similar to what Tazzioli and Stierl define as a change of paradigm, from a ‘hostile’ to an ‘unsafe environment’. ‘Offshore isolation’ incorporates the fundamental features of offshore detention, amongst which the structural lack of access to multiple kinds of resources - such as advocacy, legal counselling, general information on the self-geo-localization and time limits of this detention measure, specific information on the individual juridical conditions.

More specifically, this strategic, and creative, use of geography shrunk spaces of asylum, by affecting pathways of access to this right – along at least three main lines: access to territory (of a safe country), access to the asylum procedure, access to first reception and related services. This measure ended up reinforcing the ‘hotspot approach, by further fragmenting the information flow related to accessing the asylum procedure; thus, reinforcing and systematizing the continuum between identification and deportation. Finally, the system of quarantine ships, hindered access to a dedicated reception and to local social and health services for people with specific needs, who were rarely identified as such.

Against this background a wide array of ‘de-bordering practices’ - with the aim of resisting the offshore detention system – started to emerge in Italy. They took place through what Couldry defines as voice, the interlocution between speakers – forcibly confined people on the move – and listeners – which in this case were activists, civil society stakeholders, journalists, researchers, lawyers, cultural mediators, and politicians, supporting detainees through prise de parole actions and processes.

While migrants’ communication with the external world was prevented by the configuration of the offshore detention itself, detainees often managed to overcome these obstacles and reaching out to appropriate “listeners”, willing to amplify their voices, and at the same time co-define messages. Key topics in their interlocutions were detention conditions onboard ships, information on the temporal borders of this measure, the asylum procedure, the individual juridical status, the reporting of people with specific needs, such as unaccompanied minors, as well as the detention continuum from the ships to detention/pre-removal facilities, aimed at the deportation.

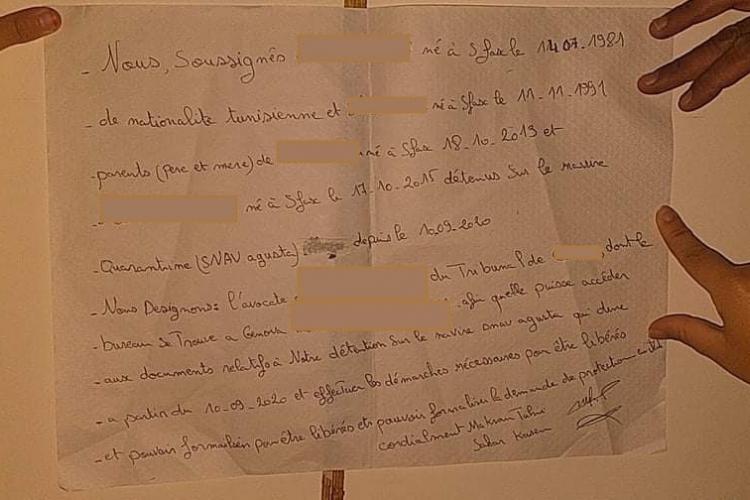

These interlocutions were articulated around some ‘de-bordering questions’, which took shape as responses to the very configuration of the quarantine ship as a border that was able to prevent people from accessing relevant information, from being visible to the onshore world and to exercise their rights. To questions like where are we? who are we? what is happening to us? What can we do to access our rights? confined migrants responded by sharing their geo-localization with relevant stakeholders (i.e. Majdi Karbai, a member of the Tunisian Parliament), including lawyers (i.e. from ASGI association) and activists (i.e. the campaign LasciateCIEntrare), by writing help requests or denouncing possible violations via social-media, by taking pictures and sharing the documents they were requested to sign (i.e, the so-called “doppio foglio notizie”, then judged illegitimate by the Italian Cassation Court), but also writing, photographing and sharing their will to claim for international protection or the power of attorney to a lawyer, in order to obtain information about their detention onboard.

These interlocutions helped migrants’ voices to jump out from physical, geographical, and procedural /bureaucratic borders, challenging the politics of (in)visibility of their bodies and identities, working as de-bordering practices.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style)

Denaro, C. (2021). Re-Bordering Policies and De-Bordering Practices in Pandemic Times: Offshore Isolation As De Facto Detention. Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2021/09/re-bordering [date]

Share: