Guest post by Karina Horsti and Päivi Pirkkalainen (University of Jyväskylä). Karina is Senior Lecturer in Cultural Policy and the director of Academy of Finland funded research project “Deportation in a mediated society: Economies of affect in the aftermath of the ‘refugee reception crisis’” (DEMESO). Päivi is a sociologist and post-doc researcher in DEMESO. This post draws on the idea of deportability as slow violence, which was developed further in a chapter in Violence, Gender, and Affect, ed. M. Husso et. al, Palgrave Studies in Victims and Victimology, 2021.

In 2015, an unprecedented number of asylum seekers arrived in Finland, like in other European countries. As a response, according to a recent study, the Finnish Immigration Service (Migri) significantly tightened its policies. Migri updated its country information on Somalia, Iraq and Afghanistan – the origin countries of most new arrivals – defining more areas as safe return destinations and therefore enabling negative asylum decisions based on the argument that internal displacement was available to asylum seekers. In addition, there was a decline in the number of cases in which fear of violence was accepted as a justification for asylum. Increasingly strict asylum criteria have resulted in more removal decisions. For instance, in March 2019 – February 2020 there were 2,5 times more decisions than in 2015.

Forced removals may involve physical coercion, and those who carry them out can potentially abuse their powers. For example, physical restraint in the moment of detention or during a deportation flight led to 17 deaths in Europe between 1991 and 2015. Several European countries have begun to monitor deportations in order to prevent the police or contracted agents from abusing human rights. Since 2017, the European border control agency Frontex requires that a monitor accompany every joint deportation flight. In Finland, monitors from the Office of the Non-Discrimination Ombudsman have been able to accompany deportees since 2014, and in the case of inhumane treatment, they can complain to the Parliamentary Ombudsman.

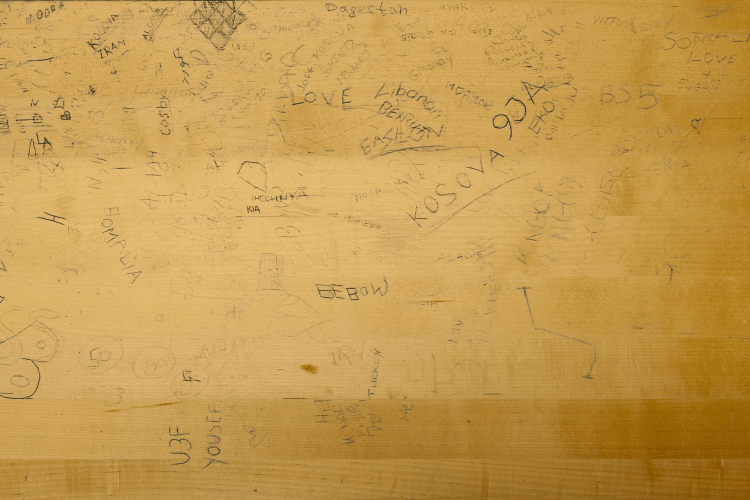

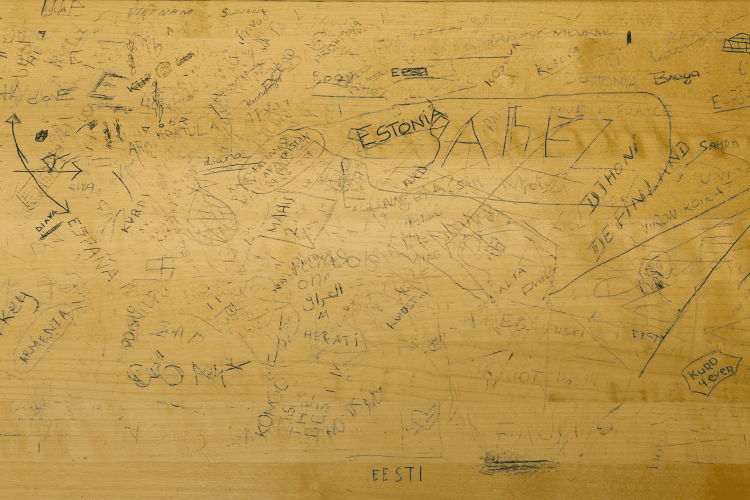

Scribbles on a table of a waiting room at Malmi police station in Helsinki where Immigration Matters were handled in 2011. Photograph from Minna Henriksson's series Communication, 2011. Photo: Minna Henriksson (Courtesy of Minna Henriksson).

http://minnahenriksson.com/main/works/2011-kommunikaatio/

Violence in deportation is often conceptualized too narrowly. It does not sufficiently consider temporalities of violence, namely, how deportability – a condition in which a person is constantly subject to the possibility of forced, potentially violent removal – gradually affects a person’s wellbeing. Deportability involves a cruelty that does not appear to be violence in the conventional sense. It is a condition that can last for years, and even if a person is granted residence, deportation may still be possible in the future. In addition, deportation has consequences that persist in time and expand over space. People may be removed to cities or countries where they do not have social ties, resulting in isolation. Often deportation carries a stigma of failure that people bear for the rest of their lives.It also tears apart important relationships, affecting family members and people who are part of the same community: teachers at school, colleagues at work, neighbors and friends.

We therefore suggest a reconceptualization of violence in deportation as what Rob Nixon calls slow violence – “a violence that occurs gradually and out of sight, a violence of delayed destruction that is dispersed across time and space, an attritional violence that is typically not viewed as violence at all”. Nixon develops the idea of slow violence by considering the pain and suffering that results from environmental neglect or disaster. He also discusses how the remnants of war – land mines and the poisonous detritus of bombs – may continue to threaten people beyond the original targets. Because slow violence disproportionately affects those with less power and money, the consequences of slow violence are fundamentally unequal.

Slow violence creates challenges for representation and perception – how can we see, hear and sense violence that seems to “just happen”, without an obvious perpetrator? How should we represent and strategically act upon something that is perhaps not visible and may not be occurring clearly here and now? While in the moment of removal and detention the perpetrators could be identified for example as border control agents or police officers, the agency in the slow violence of deportability is less obvious.

While deportation affects deportees most, in our research project Deportation in a Mediated Society (funded by the Academy of Finland) we discovered that the slow violence of deportability also affects people who are proximate to those threatened by deportation – including friends, teachers or colleagues who are citizens of the deporting country. The pain of these supporters is a collateral consequence.

In our study, we interviewed 13 people who knew asylum seekers not necessarily through activism but as friends, teachers, or colleagues. They supported asylum seekers who had received negative decisions and were under a threat to be deported to their countries of origin. Supporters of asylum seekers were alarmed by political changes in 2016, when asylum laws and policies became more restrictive. People often talked about their emotion of fear that they experienced while witnessing the consequences of deportability for the rejected asylum seekers they had become familiar with. Fear was visible in many ways: supporters feared what might happen to people in the future, or they were shocked by seeing what fear of the unknown did to people in the present moment. Supporters spoke not only about witnessing the fear-related symptoms of rejected asylum seekers but also about their own feelings of exhaustion, insomnia and anxiety.

A teacher in her forties recalled that she could not sleep after reading on the ‘Stop Deportation’ social media feed that there would be a deportation flight to Afghanistan during the night. While she was not afraid that her own asylum-seeking student would be on the flight, she nevertheless woke up at night and could not stop thinking, “Now they are taking them there, and they might be young guys, they might be like my student”. The experience of witnessing her student’s struggle with deportability sensitized her to the broader issue of deportation. She began to follow stories about deportation in the news, and the mediated witnessing of the deportation of people she did not know affected her emotionally.

The injustice the supporters witnessed and strong emotional reactions they experienced prompted them to engage in acts of solidarity. Their engagement was channeled through three types of solidarity actions: concrete assistance such as seeking out legal advice and finding ways to legally challenge deportation orders, raising public awareness of the case, or engaging in advocacy to influence decision makers and migration authorities. Each of these solidarity actions helped alleviate the effects of slow violence and its consequences. Specifically, these acts of solidarity performed by those with a legal citizenship status made visible the slow violence at the individual level, but also more broadly at the system level and societal level. This visibility is crucial because deportability tends to isolate, silence and make people invisible. For example, citizens more broadly became aware of the consequences of deportability through protests and mediated narratives. Politicians and administrators learned that the consequences touch communities such as schools and workplaces more broadly.

Therefore, it is crucial to stress that witnessing deportability in close proximity is not only about being empathetic to those who are suffering as the direct targets of injustice. Importantly, what we discovered, was that people were motivated to act upon the perceived injustice done to others. They did so by making it visible, speaking about it and documenting it for future engagements; thus, dismantling the slow violence of deportability.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style)

Horsti, K. and Pirkkalainen, P. (2021). The Slow Violence of Deportability. Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2021/01/slow-violence [date]

Share: