Guest post by Frances Timberlake. Frances has worked for four years with displaced communities in northern France, and is currently working as the UK advocacy officer at Refugee Rights Europe, focusing specifically on UK accountability at its shared border with France. She also works part-time with the Refugee Women's Centre, a grassroots association supporting undocumented women in northern France.This post is part of our themed series on border control and Covid-19.

As the Covid-19 virus has spread across the globe in recent months and governments have struggled to respond, it has been the most marginalised people who are both at the forefront of and feeling the greatest backlash from the health crisis. Those stuck at literal frontiers, trapped between the dissuasive and evasive border policies of neighbouring States, have been among them. At the UK-France border, over 2,000 people of different nationalities currently remain in limbo, with severely restricted access to basic needs such as food, hygiene and shelter, experiencing daily violence and harassment, and with almost no safe legal routes by which to leave. These people surviving in the informal settlements along the northern French coastline are those who, for a combination of reasons relating to family, community and language links, as well as negative experiences in other European countries, are hoping to reach the UK.

Despite being perhaps some of the most exposed to the Coronavirus outbreak, as well as to related lockdown measures such as increased policing and tightened border controls, these communities have not benefited from the corresponding protections afforded to local citizens.

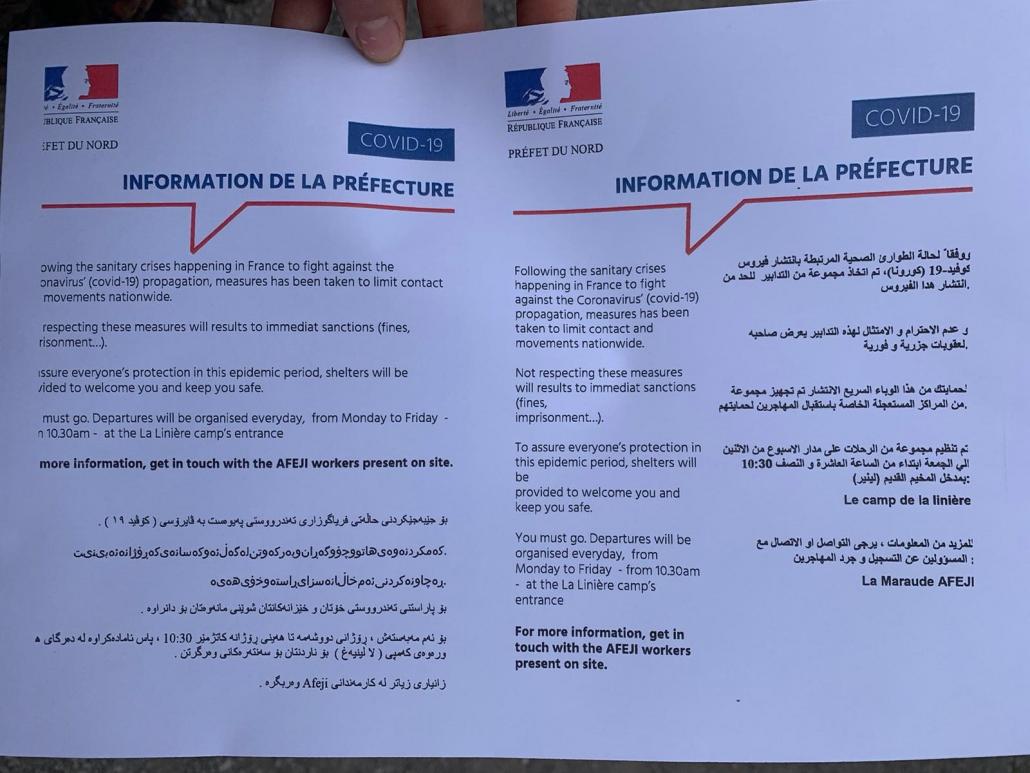

The precarious living conditions of displaced people living along the northern French coastline – in crowded tented settlements on the edges of roads, in forests or in abandoned industrial sites, regularly destroyed and evicted by heavy-handed police forces – leaves few protections against general illness, violence and harm, let alone against the global transmission of Covid-19. With one water tap for 1,100 people in Calais and the same for 500 people in Grande-Synthe, coupled with inadequate and insufficient state accommodation options and the withdrawal of many third-sector organisations providing other basic services, both physical and mental health has deteriorated rapidly among the displaced population during the lockdown. Despite calls from large consortiums of NGOs, the French government was slow to respond, repeatedly delaying an operation in Calais to shelter people whilst announcing one in Grande-Synthe upon threat of imprisonment for those who did not obey

It was, to all extents and purposes, a ‘business as usual’ response to an exceptional situation. The French continued police operations to destroy living sites without the information necessary for people to understand or trust the proposed accommodation that sometimes went with the operations. The UK continued its use of offshore detention and scaremongering promises to reduce irregular border crossings, whilst not putting any of the existing funding into assisting French sheltering operations (as has been done in previous moments of ‘crisis’ when the number of people became too high for the UK government to ignore). Meanwhile, there was no access to French asylum procedures for most of the French lockdown period, and continued obstruction of access to UK asylum procedures forced people into increasingly dangerous crossing routes, including travelling on rubber dinghies and makeshift rafts.

This is reflective of the wider cross-border policies funded by the British and carried out by the French, turning the northern French coastline into an extension of the UK’s own ‘Hostile Environment’.

Over the past thirty years, the UK has carefully exported and outsourced its border controls into northern France through a series of bilateral accords, intended to ‘detect and deter potential clandestine illegal immigrants before they are able to set foot on UK soil’ to claim asylum. In tandem, it has spent over £350 million on border securitisation in and around Calais between 2010 and the present. The agreements establish ‘juxtaposed controls’ which extend certain domestic legal powers whilst explicitly denying the possibility of placing an asylum claim to UK Border Force officials present in the UK’s ‘Control Zones’ in France, as would be possible in UK airports.

More recently, increasing semi-legal and seemingly desperate measures have been taken by the UK government to prevent ‘illegal border crossings’, resulting in further deteriorating living conditions for those at the border, a rise in dangerous journey taking and shifting money into the hands of smugglers. The increase in border security around the ports during the Covid-19 lockdown has led to increasing numbers of people attempting the Channel crossing by boat rather than by lorry. In response, the UK government and tabloid media have used the opportunity to reinforce fear of a ‘major threat’ to border integrity and sovereign territorial control. A policy named ‘Operation Sillath’ was uncovered by lawyers, which attempts to illegally return those arriving by boat directly to France, bypassing the Dublin III regulation. More recently, the Home Office decided to begin force fingerprinting those trying to cross the UK-France border irregularly. This is in order to retain data proving someone has been in France, thereby avoiding responsibility for their future UK asylum claim and justifying their removal (which is generally carried out under the Dublin regulation only if the person has registered an asylum claim in another country) . To similar ends, the UK’s Brexit negotiating team has proposed a draft UK-EU agreement that would allow for the direct return of third-country nationals to another member state they had passed through.

These measures form part of a broader, ongoing trend by the UK to offshore its immigration controls whilst ignoring its corresponding human rights responsibilities. Perhaps unsurprisingly given the echoes of Australia’s own notorious ‘Operation Sovereign Borders’ aimed at stopping sea arrivals of asylum seekers to the country, Priti Patel has reportedly approached the Australian Border Force for advice on extraterritorial border control and responding to the increase in people crossing the Channel by boat. It remains to be seen what steps they will take in the context of EU withdrawal negotiations, but the advice offered by former Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott, on preventing people arriving and sending back those who do, can provide a good guess.

While access to accommodation, suitable healthcare and asylum provisions must be opened in France in order for people to feel safe if remaining there, the only constructive way for the UK Government to address the situation in a decisive way is to make it possible for people to place an asylum claim at border points. This would make sense due to the UK already exercising sovereign powers in the border zone and therefore carrying corresponding human rights responsibilities, including the right to claim asylum. Moreover, it would help to end the decades-long, inhuman, degrading and dangerous bottleneck scenario for displaced people stuck at this border.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style)

Timberlake, F. (2020). Confined to the Border: Covid-19 and the UK-France Border Controls. Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2020/07/confined-border [date]

Share: