Guest post by Luna Vives (Université de Montréal) and Paola Arenas (Alarm Phone España). This post is part of a collaboration between Border Criminologies and Geopolitics that seeks to promote open access platforms. As part of this initiative the full article, on which this piece is based, will be free to access here for the next month.

European member states are transforming their national Search-and-Rescue (SAR) systems to avoid their legal responsibilities in areas with high migration. A recent article explores how this is happening in Spain.

The organization of maritime SAR in the Mediterranean

Protecting life at sea is a legal obligation that most governments worldwide (and all EU member states) have willingly acquired. The general terms of this obligation are established in a number of international conventions, mainly the Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS), and the International Convention on Maritime SAR.

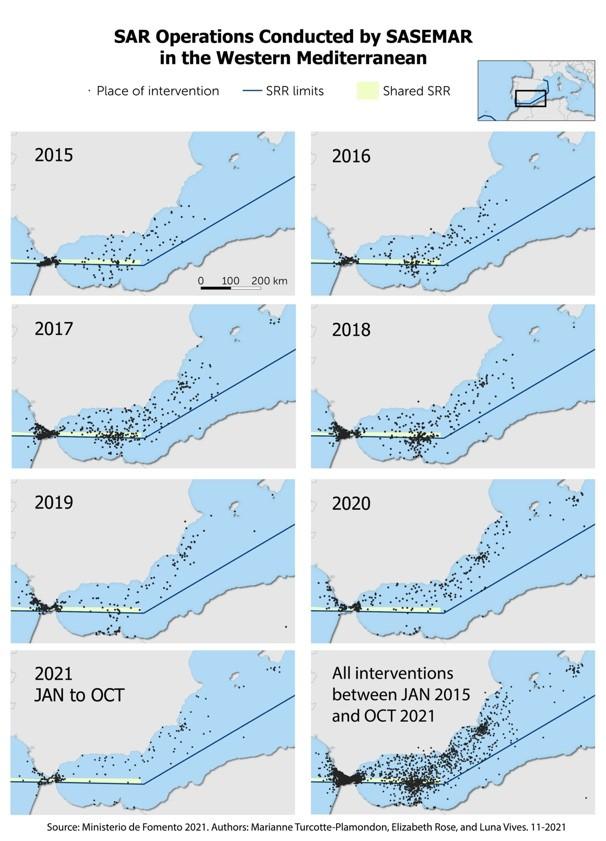

The Mediterranean is divided into Search and Rescue Regions (SRR) that are under the responsibility of coastal states (see map 1). While the obligation to implement a national SAR system applies to all signatory states, each country can decide how to do so and, specifically, which actors should be responsible for coordinating and performing rescue operations at sea. This explains the multiple and disparate SAR systems that coexist in the Mediterranean.

SASEMAR: Protecting life at sea

Maritime SAR in Spain is the main responsibility of SASEMAR, a public agency that had no operational links to the military until 2018. The agency was created in 1993 with a triple mandate: to coordinate maritime traffic, to protect the maritime environment, and to address Spain’s SAR-related obligations in the country’s SRR, which is three times its landmass. According to recent estimates from SASEMAR’s main labour union, only 10% of their operations involve migrant boats.

At the time of SASEMAR’s creation, migration was not perceived as a political problem. This explains why, even today, SASEMAR rescue crews have no law enforcement training or equipment.

Moreover, SASEMAR rescue crews are openly opposed to governmental efforts to increase the agency's border enforcement activities, as shown in the following quote from an interview with Ismael Furió, union representative:

We have not rescued a single illegal immigrant in our lives. Or even an immigrant. Never. I rescue naúfragos [shipwreck victims]. I hear there is a boat in distress with a person on board who needs to be rescued. You go to the location and sometimes you find a sailboat with British people on board, sometimes a fishing boat with fisherfolk on board, and sometimes you arrive and there is an inflatable boat with 80 people from the Maghreb.

However, the growing tension between SAR mandates to save all human lives at sea and policy priorities to keep certain people out has made SASEMAR’s expansive mandate almost anachronistic. The agency’s workers’ resistance to become part of Spain and the EU’s border apparatus (expressed in the quote above) has become more and more untenable in the face of attempts to seal the southern border against unwanted migration.

Reimagining SASEMAR: 2018 as a turning point

In 2018, SASEMAR rescued almost 50,000 migrants in the Spanish SRR in the Mediterranean – an all-time high. That same year, the government advanced plans to profoundly transform the agency. Three main strategies were central to this plan.

The first strategy involved the subcontracting of sections of the personnel through overseas private companies, the reduction of mandatory rescue crews, the replacement of permanent personnel with temporary workers, and the disrepair of vital rescue equipment. Combined, they resulted in the worsening of working conditions for SASEMAR rescue crews.

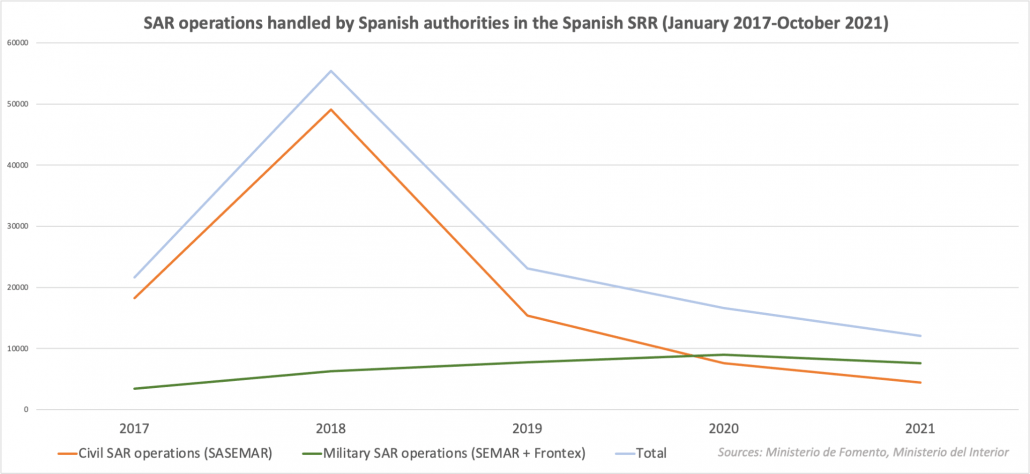

The second strategy involved the transfer of rescue responsibilities to the military. In 2018, coordination of all SAR operations in the Spanish SRR became the responsibility of the Guardia Civil -- meaning that, effectively, maritime SAR is now under military command. Shortly after this operational change, SASEMAR stopped sharing information about rescue operations on social media. At the same time, the Guardia Civil maritime service (SEMAR) has carried out a growing number of these operations in recent years, from less than 16% in 2017 to almost 63% in 2021, sometimes in cooperation with Frontex (see Graph 1 below). The militarization of maritime SAR in other countries such as Italy responded to the simple fact that militarized forces had the equipment and personnel to perform these operations. This was not the case in Spain, where SASEMAR has been responsible for rescues at sea for almost three decades. In this context, the transfer of SAR responsibilities to the military has, in fact, required the acquisition of equipment and personnel – as well as a significant loss of transparency, as detailed rescue data for operations performed by the Guardia Civil being much more difficult to access.

The third strategy involved the transfer of SAR responsibilities previously assumed by Spain to Morocco. This development is in line with what we have seen in other parts of the Mediterranean, where individual member states and the EU have sought cooperation with countries such as Libya or Turkey to prevent departures and “pull-back” migrant boats. Between 2015 and 2018, SASEMAR carried out almost a third of its operations in the Moroccan SRR, and another third in the shared zone (see map 2 below). The rationale was that the Moroccan SAR system, created in 2002, was not capable of addressing these emergencies at sea. Through their collaboration, both states were addressing their obligations in the context of the SAR Convention.

This began to change in 2018-2019. During this period, the EU and the Spanish government transferred over €170 m to Morocco, part of which was earmarked for the development of the country’s maritime SAR system. As a result, between 2019 and 2021 the line between the two SRR became a hard border that neither air nor maritime units of SASEMAR were allowed to cross (see map 2, above).

The transfer of SAR responsibilities to Morocco has signalled a paradigm shift in the protection of human life in waters between the two countries. SASEMAR rarely acts in the Moroccan or shared SRR anymore. At the same time, Morocco has a limited presence in the zone. When the Royal Moroccan Navy intervenes, they lack specialized equipment and qualified staff to carry out rescues safely. Indeed, we do not know if the rescues the Spanish government delegates to Morocco are carried out at all. We do know, however, that this arrangement has increased both the number of lives lost and the suffering of people at sea.

More deaths, less accountability

The hardening of the sea border between Spain and Morocco has led to more deaths at sea: according to data from the Spanish Ministry of Interior, 1 out of 96 people died attempting to cross the Western Mediterranean route in 2017, compared to 1 out of 38 people today. At the same time, it has become increasingly difficult to keep track of SAR operations carried out in the Spanish SRR.

SASEMAR rescue assets (e.g., boats) allow for their tracking, but changes introduced to the agency’s presence and mandate in the region mean this information is incomplete. NGOs such as Alarm Phone, AMDH-Nador, APDHA, Caminando Fronteras, and EFM-Motril perform independent monitoring of rescues at sea. However, understanding what is happening at sea has become increasingly difficult. Spain only confirms the launching of operations in the Atlantic, and Morocco does not supply this information at all or provides aggregated data on their SAR operations. Without this information, NGOs and researchers must monitor each individual operation.

The Spanish SAR system as it existed until 2018 worked: it saved lives, it was cost-effective, and it was transparent. But changes introduced since 2018 mean that the information gathered by NGOs has become an indispensable tool for researchers, human rights organizations, and migrants whose lives are at risk. Through their work, these organizations have helped locate people in distress at sea and force authorities to launch rescue operations. Without the work of these NGOs, many rescue operations would never happen.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style)

Vives, L. and Arenas, P. (2022) Death at Sea: Dismantling the Spanish Search and Rescue System. Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2022/03/death-sea [date]

Share: