New Immigration Narratives: Caravans, Family Separation, and a National Emergency

Posted:

Time to read:

Guest post by Raymond Michalowski and Frederic I. Solop. Raymond is a sociologist and Arizona Regents Professor in the Department of Criminology and Criminal Justice at Northern Arizona University. Frederic is a Professor of Political Science in the Department of Politics and International Affairs at Northern Arizona University. This is the sixth installment of Border Criminologies’ themed series on Transforming Borders From Below. The series includes short posts written by international scholars who discuss and develop ideas contained in articles published in a special issue of Theoretical Criminology on Transforming Borders From Below: Theory and Research from across the Globe.

In a recent Theoretical Criminology article titled ‘Complexity Below, Complexity Above: Intra-class Conflict, Immigration Imaginaries, and Elite Alliances in the Arizona–Mexico Borderlands’, we develop a framework for understanding how the intersection of class and race struggles ‘from below’ are reflected in competing policy narratives and policy decision-making ‘from above’. We employ this framework to better understand how struggle ‘from below’ over irregular immigration in the first decade of the 21st century altered dominant immigration discourses ‘from above’. In particular, we note that the anti-immigrant rhetoric of candidate, and now-U.S.-president Donald Trump, emerged first among white, working class, right-wing militia supporters, who most politicians at the time, regardless of party, considered as a political fringe to be held at arm’s length. In a relatively short time, as we show, the narratives of this fringe voice rose to the level of mainstream political discourse.

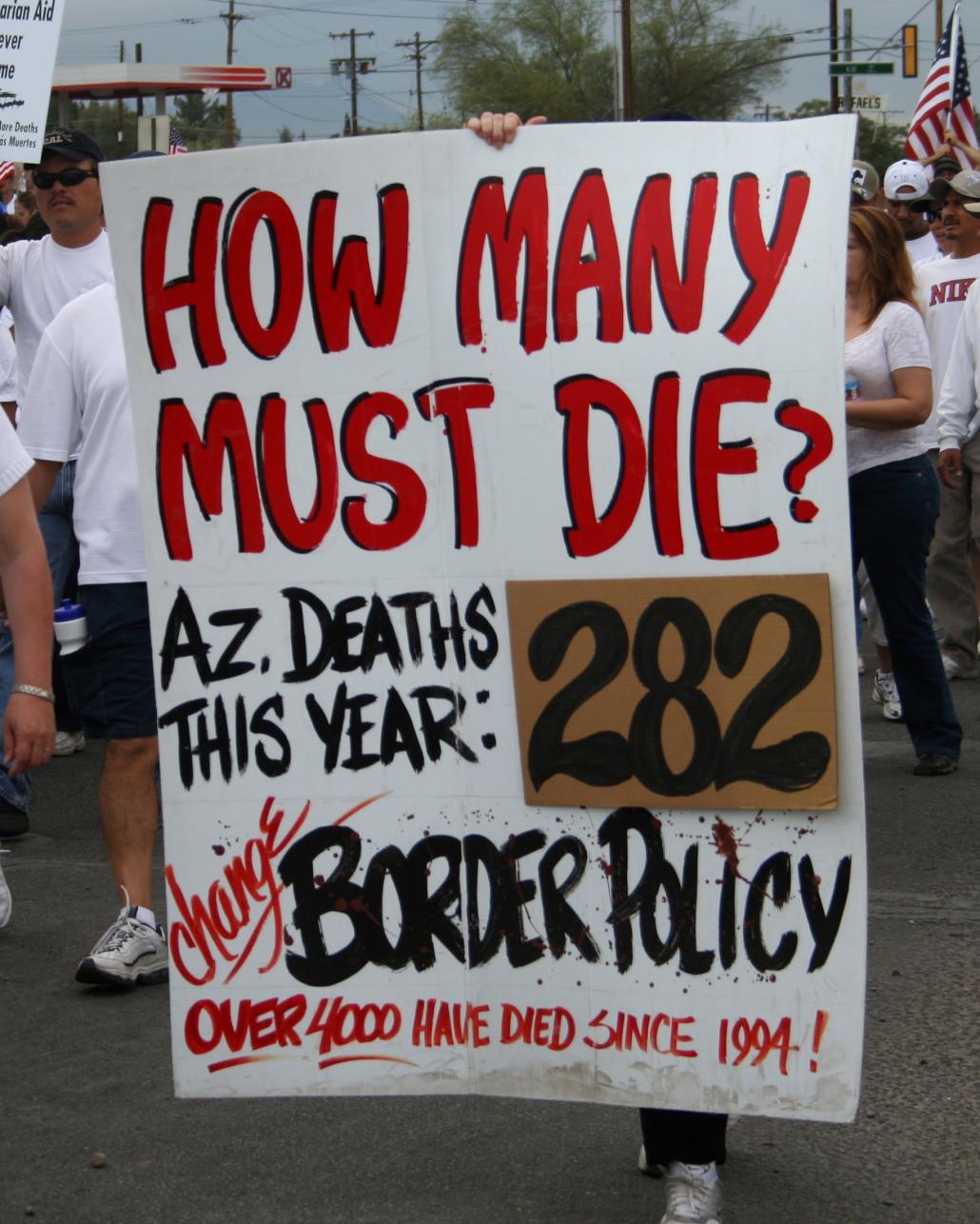

Since our article was written, the discursive environment surrounding immigration has changed somewhat in the US. During Spring 2018 much attention was brought to a national policy of ‘family separation’. Emotional images of children being taken from their parents and housed in jail-like spaces dominated the media. Later, in advance of the national US election in November 2018, President Trump incited widespread fear and hatred about advancing ‘caravans’ of immigrants. More recently, seeking funding for construction of a border wall, President Trump declared immigration to be a ‘national emergency’ requiring the diversion of federal funds and a military-level response.

The framework we developed in our Theoretical Criminology article can be applied to this changing discursive environment. In particular, we note that while competing narratives may be rooted in actual environmental changes, dominant narratives tangibly advance particular sets of interests at the expense of others. Furthermore, the competition of narratives taking place among elites ‘above’ is facilitated by vertical integration with forces from ‘below’. In this framework, we argue that social movement politics matter and emphasize the importance of paying attention to grassroots mobilizations.

This framework can be applied to current debate surrounding the word ‘caravans’. This word has been used to depict large numbers of people traveling toward the southern US border en masse with the goal of seeking entry into the United States. These caravans consist of Central Americans hoping to escape violence and poverty in their home countries. The character of immigration at the southern US border has changed as more families and groups are traveling to the US today to present themselves for asylum.

In some ways the narrative struggle over ‘caravans’ is similar to other immigration issues we discuss in our article. Those supporting asylum seekers portray the caravans as collections of honest, hard-working human beings forced by conditions in their home countries to seek a new life in the United States. Those opposing asylum, claim, among other things, that the caravans are a Trojan horse for drug dealers, criminals, terrorists, and line-jumpers who do not deserve entry ahead of those who are trying to immigrate the ‘right way.’ At the same time, the current contest between these narratives contains a new element: debate over the role of asylum. Unlike elsewhere, until recently asylum-seeking was a limited component of irregular immigration at the U.S. southern border. Driven in large part by fears about the deterioration of physical safety and food insecurity in Central America, asylum applications in the United States grew from around 5,000 in 2007 to 92,000 in 2016 (the last year for which Homeland Security provides complete statistics). With the arrival of caravans, these numbers are expected to be even higher for more recent years.

Caravans and the related increase in applications for asylum in the United States pose complex legal and moral questions about who deserves access to relative freedom from violence and extreme want. The current debate pits the ideology of President Trump’s America First policy against both national and international law governing not only the right to apply for asylum, but also the right to leave one’s country. On this last point, Donald Trump has argued that, contrary to international law, Mexico, Guatemala, and Honduras should deny potential asylum seekers the right to join caravans heading to the United States.

As we note in our Theoretical Criminology article, President Trump focused national attention on caravans in advance of the November 2018 US election. His characterization of caravans included images of unruly mobs advancing angrily to the southern US border. He accused Democrats of shackling his efforts to protect the homeland. Mainstream media outlets such as PBS and the Washington Post called out President Trump for his use of anti-immigration language and imagery as an attempt to influence election outcomes. His strategy for electoral success included mobilizing anti-immigration voters around issues of racial hatred, fear, and the need to support law-and-order Republicans at the ballot. This strategy resonated with some grassroots voters already beset by racial hatred and fear of the other. Although this strategy failed to prevent the House of Representatives from switching to Democratic leadership, it helped the Republicans maintain control of the Senate.

Our article directs attention to fundamental questions about who wins and who loses in the horizontal struggle for control of power and resources. Further, it emphasizes the importance of analyzing the relationship between what is taking place among elites ‘above’ and grassroots actors ‘below’ to fully grasp the complexities that underlie narratives about issues such as immigration. While we apply this framework to recent dialogue about caravans in this blog entry, our framework can also be applied to narratives about family separation at the border and the Trump administration’s co-optation of the idea of a ‘humanitarian crisis’ to justify further militarization of the U.S.-Mexico border. It is important to think multi-dimensionally about the origins and impacts of political narratives.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style)

Michalowski, R. and Solop, F. I. (2019) New Immigration Narratives: Caravans, Family Separation, and a National Emergency. Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2019/05/new-immigration (Accessed [date])

Share: