Guest post by Daniel Quinteros, MRes in Criminology (University of Manchester) and Joint Researcher at Instituto de Estudios Internacionales, Universidad Arturo Prat – Chile. Daniel’s interests are related to the fear of crime and border control. Using a mixed-methods approach, Daniel is currently conducting research on micro-level inter-ethnic conflicts and the construction of an index for measuring emotional responses to crime in Chile.

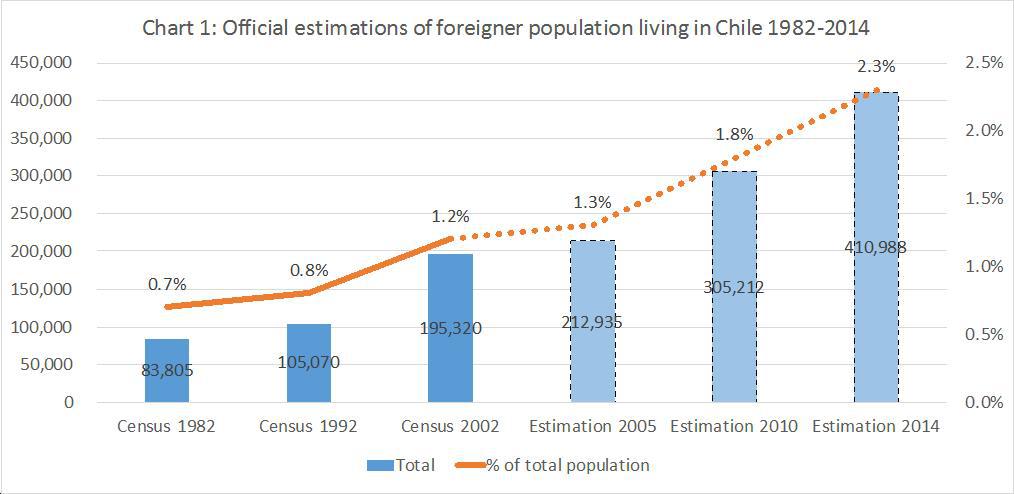

Economic crises and the tightening of border controls of industrialised countries have given rise to new intra-regional migration patterns within Latin America. Chile, due to its economic and political stability, has rapidly become one of the main intra-regional destinations. It is estimated that from 1992 to 2014 the foreign population in the country quadrupled in size, reaching over 400,000 people. Those migrating mainly come from Peru, Argentina, Colombia, Bolivia, and Ecuador, and more recently from the Dominican Republic and Haiti. Hence, Chile has quickly transformed from a country of emigration to a receiving country of migration. However, Chile’s response to the influx of irregular population in recent years is questionable on a number of grounds, which I aim to highlight in this post.

Despite some notable improvements in the provision of health care and education, the ratification of several international human rights treaties and two regularisation programmes in response to the growing numbers, migrants entering Chile and those who are already living in the country still face a number of restrictions. The Border Control Act 1975 (DL 1094) is the main legal framework governing migration in Chile. In considering foreigners as a possible threat to the nation, this piece of legislation sets the ground for highly discretionary practices. For example, it gives administrative powers to border control officers, who, without specific guidelines, can decide who can enter the country or not, and can issue expulsion orders without due process or judicial oversight. The power to ban ‘undesirable elements’ from entry to the country is not a new legislative provision. It was previously foreseen by the Residence Act 1918, in response to, for instance, Europeans causing political agitation or allegedly promoting communist or anarchist thinking. Later, the Immigration Department Act 1953 sought to promote a selected migratory flow to encourage the occupation of land in uncultivated areas and ‘improve the race’ by allowing white European males to populate the country. The DL 1094 did not just keep some of the selective principles of previous legislations, it also expanded the punitive control by incorporating further restrictions and creating new immigration offences punishable with fines, imprisonment, or expulsion.

At the northern border with Peru and Bolivia, many of those wishing to migrate are banned from entering the country almost without any consideration of their individual circumstances. Those that are not allowed into Chile are exposed to a number of dangers - not only do they face harsh conditions due to the altitude and barren desert, they are also vulnerable to human trafficking organisations as well as facing death due to landmines that remain in the area from the coup d'etat of the 70s. Those who actually make it across the border, face persistent discrimination in their dealings with public authorities. For example, there are over 2,000 infants registered as ‘child of an in-transit foreigner’, which serves to deny Chilean-born children nationality.

Furthermore, data I have gathered and analysed here, shows that 96% of border control sanctions do not include migrants’ statements regarding the alleged infringement, thus violating DL 1094’s obligation to consider them prior to sentencing ‘whenever possible’. On average 1 out of 20 sanctions imposed are expulsions, but in the case of citizens from Bolivia that rate goes up to 1 out of 5, and for Dominicans 1 out of 3, pointing to the discriminatory performance of border control policy. More often than not, irregular entry is treated as a crime by the authorities, in order to evoke the immigrant’s immediate expulsion, without offering access to an appeals procedure. However, expulsion is not only imposed as a response to an alleged crime, but is also enforced as an ‘obligation to leave’ together with warnings and fines.

Border control policies in Chile resemble more familiar forms of punishment in the criminal justice system, yet operate with much fewer safeguards. Therefore, people who have been in contact with criminal justice agencies -even if only as suspects- or those considered as a potential economic burden to the receiving society are more likely to be expelled or refused entry. In doing so, border control policies act as a ‘regulating valve’ stemming the flow of ‘non-desirable’ Latin Americans. The evidence presented here and the multiple lives lost at the northern border, arguably warrant a border control policy that fully accounts for the integration of the migrant population. This was indeed one of president Bachelet’s campaign promises under her second administration. There is little time to lose for those suffering at the borders or at the hands of the police in detention sites. It is time for a new border control policy.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style)

Quinteros, D. (2017) Time for a New Border Control Policy in Chile. Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2017/03/time-new-border (Accessed [date]).

Share: