Guest post by Jaka Kukavica and Mojca M. Plesničar. Jaka is a student at the Faculty of Law, University of Ljubljana and a research assistant at the Institute of Criminology. Mojca is a Research Fellow at the Institute of Criminology at the Faculty of Law and Associate Professor at the University of Ljubljana, Slovenia. Her areas of teaching and research are mainly in the fields of sentencing and punishment, but also include issues of age, gender and nationality in connection to crime and punishment as well as the uses of new technology in these fields. They were both part of a project at the Institute reporting on the flow of migrations from October 2015 to June 2016 for the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. This is the second instalment of Border Criminologies’ themed week on the Lawlessness of the Refugee crisis organised by Jaka and Mojca.

In our previous instalment, we discussed the creation of a de facto humanitarian corridor on the Western Balkans migration route in late 2015 and its operation through March 2016. The establishment of the corridor enabled refugees and migrants to travel freely from Greece to Germany and northern Europe without having to demonstrate their right to enter Schengen territory at the borders. We argued that the emergence of the humanitarian corridor was not established by law, which created a continuing state of lawlessness. In this piece, we focus on how the corridor operated in practice, arguing that the lawlessness of its existence led to illegitimate deprivations of liberty in the systematic and continuous limitations on peoples’ movement as they travelled through the corridor.

Impermeability of the corridor

Even though the corridor enabled people to travel freely to their desired destination, refugees and migrants were not permitted to move freely. To fully comprehend the extent to which the liberty of people was deprived, a closer look at the nature of the corridor in Slovenia might be helpful. While the description below depicts a certain point in time, it inevitably simplifies how the humanitarian corridor worked as the specifics of migration managements were continuously changing, sometimes on a daily basis. It does, however, demonstrate the general principle under which the corridor operated.

Contrary to the earlier stages of mass migration when people would irregularly cross borders in a disorganised and uncontrolled manner, in the autumn of 2015 peoples’ freedom of movement began being systematically restricted when the humanitarian corridor became the modus operandi. Refugees and migrants typically entered Slovenia from Croatia at the Dobova border crossing, travelling by train as organised by the Croatian authorities. When a train arrived in Dobova, Slovenian authorities – the Police and sometimes even the military – together with volunteers were already waiting at the railway station. People were not allowed to leave what was usually an overcrowded and unhygienic train (carrying up to 1,000 people per train) until they were given permission from the authorities to disembark. Such permission, in turn, was contingent on the capacity of the nearby registration centre. This system occasionally resulted in grotesque and disturbing scenes where people were not permitted to leave the train, even to access the toilet, for hours. As a result, a number of people were reported to have urinated themselves while being forcefully held on a train.

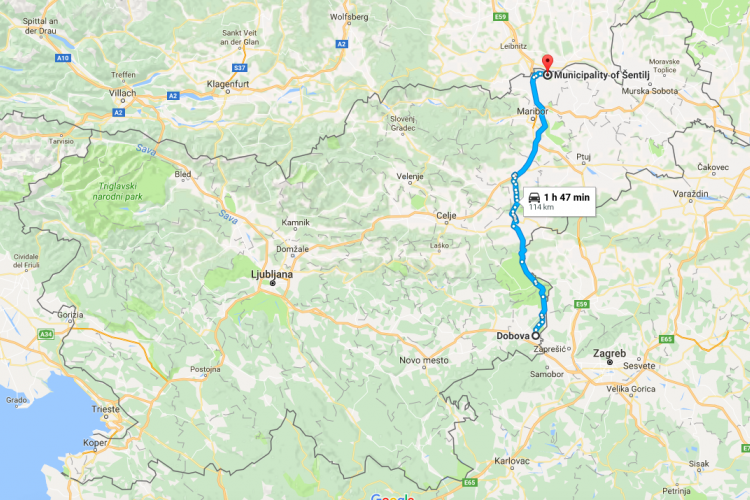

After the authorities allowed people to disembark, refugees and migrants were escorted within a confined, fenced area by armed members of the police force to a nearby registration centre. There, still confined and monitored by the police, they were registered by the competent authorities. People were then escorted to a tent where they were not permitted to leave, except to grab some air in the fenced off surrounding area. Whenever the transportation to Austria organised by the Slovenian authorities was ready, either the police or the military escorted people onto the buses that had been waiting to take them to the next border. All of this took place within a confined area around the registration centre in Dobova. On the buses, too, there was a heavy police presence to take refugees and migrants to the border with Austria, most often to the Šentilj border crossing. Whenever Austrian authorities were not prepared to admit people outright, the Slovenian police took them to the Šentilj accommodation centre, from where people were not permitted to leave. When Austrian authorities were ready to begin admitting refugees and migrants, they were escorted from the accommodation centre and handed over to Austrian authorities for registration.

Not once during their journey through Slovenia were people on the humanitarian corridor permitted to move freely. To the contrary, even when refugees and migrants were not detained in inhumane conditions in an overcrowded train or bus, their movement was constrained to a very limited area within the registration or accommodation centres. In the most extreme cases, when registration, transport to the Austrian border, and admittance to Austrian territory all operated at an extraordinarily slow pace, deprivation of their liberty lasted for days.

Why does legality matter?

Just as domestic and EU legislation did not and does not foresee the creation of a humanitarian corridor, by the same token and as a logical consequence, it did not (and still does not) allow for the deprivation of liberty and of freedom of movement (p. 41). These characteristics are, however, inherent to the creation of a corridor: it is not much of a corridor if it is not impermeable.

The lack of a legislative framework may seem perfectly natural, understandable, and even desirable. However, as soon as we permit people, whether citizens or foreigners, to be detained without a valid legal basis and without regard to the due process of law, a serious rule of law issue arises. Whatever freedoms people mostly falsely credit the Magna Carta for, one of the freedoms that actually dates back to 1215 is the freedom from being detained without a legal basis, i.e. freedom from arbitrary detention (and freedom of movement as an ancillary). And for good reason. Detention with no legal basis fundamentally undermines the ideal of the rule of law and replaces it with the rule of authority and the rule of force. An individual no longer loses her liberty due to violating a norm prescribed by a complex legitimacy enhancing system of a constitutional democracy, but instead because an individual or a group of individuals in positions of power decided she ought to lose her liberty.

However, this is much more than a theoretical issue, the lawlessness of the humanitarian corridor and the situation that surrounded it had a direct impact on individuals and led, on some occasions, to rather Kafkaesque occurrences. For example, in November 2015 a relatively large number of Moroccan citizens were arbitrarily separated from the corridor and taken into immigration detention in Postojna. The authorities provided no explanation why this group was treated differently than everybody else nor did they provide a legal basis for detaining the group of Moroccans.

It seems slightly odd that there even is a need to state this in modern day Europe, but it is only when breaches of individuals’ rights, especially the right to liberty, are based in law, that such arbitrary exercises of state power can be curtailed.

In the next and final instalment, we will address the effects the lawlessness of the humanitarian corridor had on the rights of (unaccompanied) children and other vulnerable persons that were travelling inside the corridor.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

Share: