‘From One Police State to Another’: Stories of Deportation from the United States to El Salvador

Posted:

Time to read:

Guest post by Kelly Birch Maginot. Kelly is a graduate student in Sociology at Michigan State University. Her research focuses on international migration, gender, and citizenship. Her dissertation explores how deported Salvadorans and their loved ones understand and practice social, cultural, and political citizenship in the United States and El Salvador. She is a 2015-2016 Inter-American Foundation Grassroots Development Fellow. Her pre-dissertation research was made possible through a Tinker Field Research grant from Michigan State University. This post is the sixth installment of the Border Criminologies Themed Week on Deportation Threat, Realities, and Practices in the United States organised by Tanya Golash-Boza.

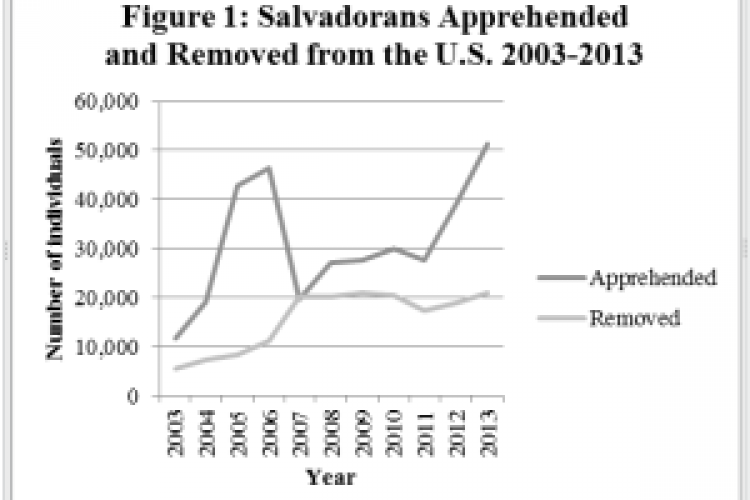

Despite El Salvador’s small size, more than 19,000 deported Salvadorans arrive from the US annually, and this number continues to grow (see Figure 1). According to the US Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Salvadoran nationals are the fourth highest group of migrants detained in and deported from the US. These men and women often have lived in the US for years, and they may feel more at home there—as undocumented immigrants or temporary residents—than in El Salvador, which is their legal and native home.

During Summer 2014, I spent a month speaking with deportees and their family members at El Salvador’s Bienvenido a Casa (Welcome Home) office, a government-sponsored program that greets deportees when they arrive from detention centers across the US. I followed up by undertaking 10 in-depth interviews with deported men. Their stories of detention, deportation, and reintegration reveal the challenges they face and their resistance to these injustices.

Experiences of Immigrant Detention

Salvadoran deportees recalled maltreatment in detention centers including low temperatures and limited food. In hieleras (iceboxes), air conditioning and fans blew cold air, while detainees were rarely given blankets or sweatshirts. One deportee remembered that the rooms were not only cold but also dirty and crowded. Detainees also reported being fed small, bland meals that left their stomachs grumbling: ‘The food is very poor and you go to sleep hungry and wake up hungry.’

The Deportation Journey

The journey from the US to El Salvador intensified deportees’ frustrations. They often arrived in El Salvador feeling dirty and uncomfortable. In the hours leading up to deportation, detainees were unable to shower, brush their teeth, or even use the bathroom privately. Some men recalled being unable to sleep because they were shackled at the hands, feet, and waist while kept in small cells, buses, or airplanes. While handcuffed, they were reminded on the airplane that, in case of emergencies, they would need to put on their oxygen masks, prompting the question: ‘How can I reach my hand to the oxygen? I can’t even reach my food to my mouth.’

These examples show how detainees and deportees are disempowered by the US immigration system. They may encounter additional harassment and prejudice in El Salvador, where they’re mistaken for gang members or criminals—even though most Salvadoran deportees are removed for non-criminal reasons. This has prompted Pablo Alvarado to describe the deportation experience as a transfer ‘de un estado policial a otro estado policial’ (from one police state to another).

Resistance in the Face of Injustice

Despite these experiences and obstacles, deported Salvadorans found ways to maintain their dignity and resist injustice in detention centers, during deportation proceedings, and after returning to El Salvador. For example, one bilingual deportee recalls a moment when a security guard was repeatedly calling the name of one of the detainees with no response, because she’d been using the wrong accent and thus wasn’t understood. He remembers, ‘She said, “I've been calling and he's stupid.’ I said, ‘No, he's not stupid. He just doesn't speak English, just like you don't speak Spanish.” A lot of people with me couldn’t speak English, so they would ask for my help. Of course, I [helped]. If they needed an interpreter, I raised my hand. I always want to help.’ Another man would sing traditional folk songs in the detention centers to build morale, and still another participated in a hunger strike to change the center’s poor conditions.

- Monday, 27 April: Deportation Threat, Realities, and Practices in the United States (T. Golash-Boza)

- Tuesday, 28 April: US Immigration Enforcement at a Crossroads: What Can we Learn from the ‘Secure Communities’ Program? (J.M. Pedroza)

- Wednesday, 29 April: Immigrant Health in la jaula (M.E. Young)

- Thursday, 30 April: ‘A Recession-Proof Industry’: Reagan’s Immigration Crisis and the Birth of the Neoliberal Security State (K. Shull)

- Monday, 4 May: Punishing Immigrants: The Unconstitutional Practice of Punitive Immigration Detention in the United States (C. Wheatley)

- Tuesday, 5 May: ‘From One Police State to Another’: Stories of Deportation from the United States to El Salvador (K. Birch-Maginot)

- Wednesday, 6 May: Welcome Home? Deportation to El Salvador (K. Dingeman-Cerda and E. G. Kennedy)

Any thoughts about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style):

Birch-Maginot, K. (2015) ‘From One Police State to Another’: Stories of Deportation from the United States to El Salvador. Available at: http://bordercriminologies.law.ox.ac.uk/stories-of-deportation/ (Accessed [date]).