Guest post by Michele Pifferi, Associate Professor of History of Medieval and Modern Law at the University of Ferrara, Law Department, Italy. Further details about the historicisation of the freedom to migrate, along with the comparative analysis of the laws regulating its exercise, are addressed by the research agenda of the project Migration Policies and Legal Transplant in the Mediterranean Area.

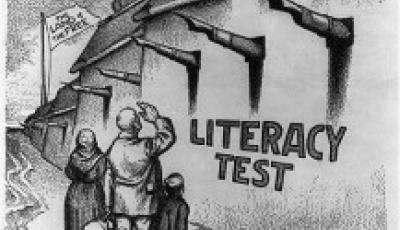

Historians have long been interested in migration. Over the last decade the field of ‘global history’ has generated a number of research projects and publications on this topic. Legal historians, however, have remained mostly on the sidelines of this cultural trend, as though the laws regulating the freedomto move―ius migrandi―are secondary to the social, economic, demographic, and political ‘push and pull’ factors. In this post I challenge this tendency, taking an historical approach to the right to migrate in liberal democracies, using the United States (as a country of immigration) and Italy (a nation of emigration) as examples.

Italian emigration laws and the idea of a soft colonization

If we look at the two Italian emigration laws (1888, 1901) passed during the great migration wave, the ambiguities and the limits surrounding the freedom to move appear even more clearly. In both acts, article 1 declares that emigration is free, except for the limits provided by the law. What are these limits? They basically consist of military service duties, sentences, administrative requirements (such as a passport or visa), and in temporary limitations to settle in specific regions stipulated by the government for public order policing. Parliamentary debates shed light on the liberal paradox that free emigration is a principle of natural law but the state can always interfere in its enjoyment because the right of the country prevails over the individual right to leave the homeland. Clearly driven by utilitarian economic reasons, lawmakers try to control and exploit what cannot be prevented: the emigration of the poorest part of the population (see, for example, Enrico Ferri's argument about emigration as a safety valve for the society, insofar as it relieves demographic pressure that produces unemployment and poverty). Admitting the impossibility of improving the welfare of the whole population (especially in the South), the government embraces a Janus-faced rhetoric, recognizing that emigration “is a historical, normal, perpetual phenomenon of mankind,” which cannot be barred because the modern country “is not a territory but a flag, i.e. a moral unity that is not destroyed by material distance (…), because in the economic system it is a new force of production and consumption opening new trade markets; it is, in the political order, a pacific spread of the Italian descent, language, sentiments, and institutions; it is, in the ethnographic order, the generation of populations; it is, in the humanitarian order, the civilization and the cultivation of the world” (R. De Zerbi, Relazione). Instead of contrasting it, or of solving its causes, the lawmaker’s strategy is to take advantage of emigrants, regulating and helping their departures, journeys, arrivals, and hopefully remittances (with Italian banks abroad). The limited and controlled right to emigrate conceals a political project of soft and peaceful colonization (especially in relation to the emigration towards Rio de La Plata).

This outline of the restrictions surrounding the ius migrandi at the turn of the twentieth century in a country of mass emigration (Italy and a country of immigration―the U.S.) unveils some of the liberal state’s contradictions. The rising apparatus of protections and services offered by the welfare state to citizens was denied, or only partially granted, to aliens. Border control was a cornerstone of every nation building policy. Only the universalistic perspective of the post-WWII human rights movement started challenging this frame. Today’s inconsistencies and deficiencies of migration laws have deep historical roots, related to the supremacy, ever changing but persistent, of the sphere of public interest and social security over the individual freedom.

Any thoughts about this topic? Post a comment here or on our Facebook page. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style): Pifferi M (2014) Ius migrandi: The Legal History of an Unrecognized Right. Available at: http://bordercriminologies.law.ox.ac.uk/ius-migrandi-the-legal-history (accessed [date]).

Share: