Do shadow banks—nonbank investment companies like debt funds and real estate funds—pose systemic risks? US Securities and Exchange Commission Chair Paul Atkins has said that he and at least some other regulators agree that ‘non-bank financial institutions don’t pose systemic risk to our markets’. The CEO of Apollo Global Manager, a large private equity firm, recently stated that people have ‘lost their minds’ over private credit, calling concerns about systemic risk ‘overblown’ and ‘hysteria’. Still, others worry that private credit could contribute to another financial crisis like the one in 2007 and 2008.

My new working paper, Safekeeping Too-Big-To-Fail Banks from Private Credit, shows that a financial shock to private credit funds, real estate funds, and other shadow banks could spread to the US banking sector through an economically significant equity investment channel. The paper establishes that the banking sector is not merely a lender to the shadow banking sector, it is a significant owner of it. Regulators must now assess the private capital markets and banking sectors interdependently. The paper analyzes these issues in the US context, but parallel questions are gaining attention in the United Kingdom and Europe, as evidenced by the House of Lords Financial Services Regulation Committee recent inquiry into the growth of private markets in the UK.

The paper reports that, by the beginning of 2024, US bank holding companies in the aggregate held almost $50 billion of equity and other investments in ‘real estate ventures’; $80 billion in non-controlling investments in ‘other joint ventures’; and almost $62 billion of exposures to nonbank variable interest entities, like collateralized loan obligations. In the second quarter of 2020 (my last quarter of full data), bank holding companies in the aggregated reported equity investments of $55 billion in ‘nonfinancial’ companies (including real estate funds).

Equity investing by banking organization in private investment funds is relatively new in the United States and has exhibited explosive growth. Starting around the 1990s, Congress and regulators gradually granted US banking organizations the choice to hold ownership interests in funds inside or outside the regulatory perimeter. What guides this choice for banking organizations?

The Article offers a regulatory arbitrage explanation. If the government provides a de facto guarantee for too-big-to-fail banking organizations, market discipline fails to constrain the well-known moral hazard problem: banks have incentives to assume excessive risk from the perspective of society. In the theory of banking, prudential regulation is supposed to step in where market discipline leaves off. However, equity investments in nonbank private funds enable a pathway to partial evasion of regulatory constraints. Banking organizations can partially own, sponsor, and backstop private credit and real estate funds that pursue risky strategies the bank cannot itself undertake.

Consider the example of a direct lender private credit firm—an investment fund that makes loans to businesses. If banking organizations lend through a wholly owned subsidiary, that entity is regulated as a bank. But if banking organizations make a minority investment in a private credit investment fund, the fund is not regulated as a bank (and it’s structured to be exempt from investment company regulation too). Private investment funds are able to hold risky assets like distressed debt, payment-in-kind debt, and convertible debt, all without prudential oversight. And private investment funds operate outside the whole suite of banking regulations, including capital rules, restrictions on affiliate transactions with banks, and the Volcker Rule, among others.

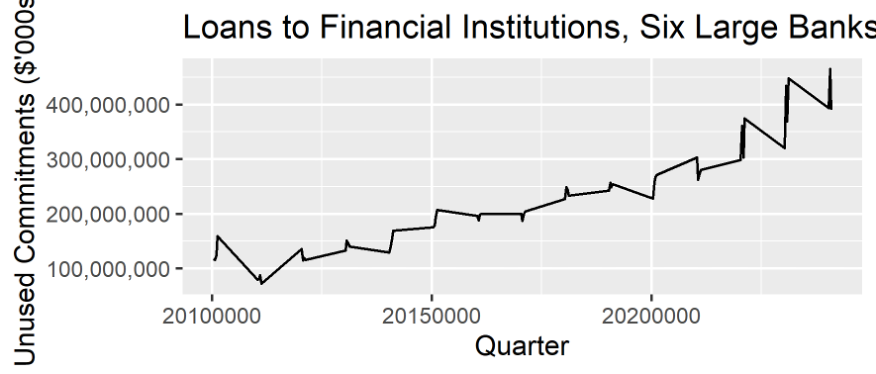

Equity investments by banking organizations can also subtly change incentives and deal structures. For example, consider that the data also shows that depository institutions have committed over $500 billion in unused loan commitments to nonbank financial institutions.

In a financial crisis, private funds will draw down unused commitments from banks, effectively making banks a conduit for private investment funds to access the Federal Reserve’s lender-of-last resort facilities. By creating liquidity insurance and removing risk from equity and subordinated debtholders, unfunded loan commitments to private investment funds subtly undermine market discipline in the capital markets. Widespread emergency lines of credit incentivize the creation of fragile, runnable financing structures in capital markets. The historical precedent here is the episode in 2007 run on asset-backed commercial paper conduits, sparking drawdowns of bank-provided liquidity guarantees, a widespread credit crunch, and a global financial crisis.

My findings on the equity investing channel complement other research showing that banking organizations are exposed to private credit through a debt channel. There is also commentary showing that insurance companies are heavily invested in private credit. All of this research suggests that the financial sector is interconnected through the private credit industry, emphasizing the importance of accountability by prudential regulators.

What lesson does the analysis in the paper provide for regulators? I offer a few of my own views below.

First, regulators should require banking organizations to publish detailed financial disclosures about their equity investments with disaggregated, granular information and narrative disclosures about known risks and uncertainties. Sunlight is a good disinfectant, and one that is currently lacking.

Second, regulators should require banking organizations to unwind—and ultimately, they should prohibit—unfunded commitments to bank-sponsored investment funds as unsafe and unsound practices.

Finally, Congress should reconsider the authority of banking organizations to invest in ownership interests of private credit and real estate investment funds at all. The Volcker Rule carves investments in these funds out of its prohibitions. But it probably should not if we heed the lessons of 2007-09. If banking organizations want investment exposure to real estate or debt assets, they should do so inside the regulatory perimeter, not through unregulated investment funds.

The full working paper is available here.

Patrick Corrigan is a Professor of Law at the Notre Dame Law School.

OBLB types:

Jurisdiction:

Share: