Eric E Posner and E Glen Weyl recently stated in their book, Radical Markets, that ‘If we aspire to prosperity and progress, we must be willing to question old truths, to get at the root of the matter, and to experiment with new ideas'. In recent years, financial markets have focused their attention on cryptocurrencies, which led to the proliferation and development of cryptocurrencies across multiple jurisdictions (eg Libra, Saga, JPM Coin, and even tokenised art works), but regulatory authorities have not gotten to the root of protecting the retail investor from various risks of cryptocurrency offerings, nor have they developed an international standard for regulating cryptocurrencies. Cryptocurrency businesses are instead required to consider various legislative frameworks and tailor their services to local regulatory treatments of cryptocurrencies.

In my recent article, Crypto Conundrum Part I: Navigating Singapore’s Regulatory Regime, I observe that there is a disparate legislative framework applicable to cryptocurrencies in Singapore, which presents a regulatory conundrum for companies, regulators and retail investors. This article also provides an analytical framework for examining cryptocurrencies under the current regulatory framework in Singapore, and argues that the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) should get at the root of the matter, and consider the following two issues: (a) is the current regulatory framework an unnecessary regulatory cost for cryptocurrency businesses? and (b) does the current regulatory framework restrict Singapore’s regulatory authorities from safeguarding the interests of retail investors?

In Singapore, three separate legislative acts may apply to cryptocurrencies—namely the Securities and Futures Act (SFA), the Commodity Trading Act (CTA), and the recently enacted Payment Services Act 2019 (PS Act), which came into force in January 2020. Cryptocurrency businesses will be required to apply for licence under the SFA, CTA and/or PS Act if their cryptocurrencies may be considered (a) a ‘capital markets product’ under the SFA; (b) a ‘commodity’ under the CTA; and (c) a payment service under the PS Act.

Companies that choose to raise capital by selling cryptocurrencies that constitute ‘capital markets products’, a statutory defined term under the SFA, are generally required to comply with prospectus requirements or rely on certain exemptions under the SFA. Cryptocurrency businesses should also consider whether a cryptocurrency is a regulated ‘commodity’ under the CTA. The CTA, its regulations and related notices issued by Enterprise Singapore collectively regulate and impose certain restrictions on trading of commodities in Singapore. Cryptocurrencies may also be regulated as a payment service under the PS Act if they fall within the statutory definitions of ‘e-money’ or ‘digital payment token’ (DPT).

There is an unnecessary regulatory cost for cryptocurrency businesses, especially at their initial stages of development, when they may only apply for one licence—a capital markets services licence under the SFA to deal in cryptocurrencies that appear to be securities. However, commercial developments might force cryptocurrency businesses to apply for a second licence under the PS Act when the cryptocurrency becomes widely used as a payment service.

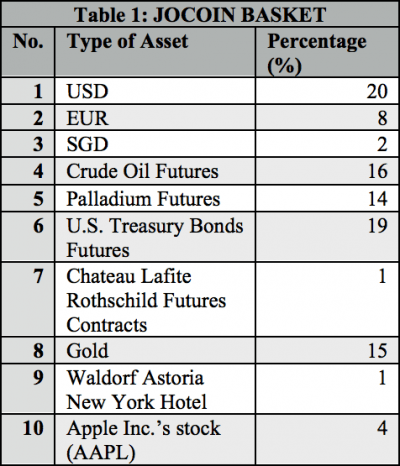

Further, as illustrated in Crypto Conundrum Part I, the PS Act does not permit MAS to regulate evolving and complex cryptocurrencies (eg where stable coins pegged to more than one currency, and stablecoin holders might not have a claim on their issuer). This form-over-substance approach prevents MAS from regulating cryptocurrencies backed by a reserve with complex baskets. Consider the following hypothetical cryptocurrency (JOCOIN):

Assume that (a) holders of the JOCOIN may convert certain units of JOCOIN immediately into USD, euro, SGD, AAPL stock or into gold bars with third parties or the issuer; (b) in exchange for not selling every block of 1000 JOCOINs for two years, purchasers who own 1,000 JOCOINs may exercise an option to redeem a case of Chateau Lafite Rothschild wine in two years; (c) in exchange for not selling every block of 10,000 JOCOINs, purchasers who own a block of 10,000 JOCOINs may exercise an option to be delivered a barrel of crude oil, or a certain amount of palladium; (d) US Treasury Bonds are redeemable for every block of 100,000 JOCOINs in three years from the date of issue of JOCOINs; and (e) participants in the initial JOCOIN sale are issued a preferred category of JOCOIN which represents shares in Waldorf Astoria New York Hotel.

Based on the hypothetical and assumptions above, JOCOIN might be considered a capital markets product, a commodity and/or a DPT. While MAS has recently stated that if a cryptocurrency is regulated under the PS Act, it will generally not be regulated under the SFA, and in the light of the fact that certain cryptocurrencies might not be regulated under both the PS Act and SFA, I urge MAS to adopt a broad, simple framework in order to regulate potential complex cryptocurrencies like JOCOIN more effectively.

As a sequel to Crypto Conundrum Part I, 'Crypto Conundrum Part II: A Multi-Jurisdictional Uncertainty' surveys various regulatory attitudes towards cryptocurrencies, and contrasts various regulatory enforcement actions against cryptocurrency businesses. This multi-jurisdictional framework reveals that US and Europe, unlike Singapore, have adopted a substance-over-form approach, and have engaged in punitive enforcement actions in the cryptocurrency space. Despite being one of the leading financial hubs for cryptocurrency offerings, there has been a relatively low number of enforcement actions in Singapore.

It is submitted this may stem from either the inapplicability of Singapore’s form-over-substance narrow framework encapsulated by the SFA, CTA and the PS Act or a deliberate regulatory choice. Where it is the former, I argue that MAS should achieve regulatory simplification by expanding the definition of ‘security’ under the SFA to safeguard the interests of the retail investor under securities law. I recommend MAS to consider amending the SFA and importing common law doctrines developed in the US following the US Supreme Court Howey test (SEC v W J Howey Co 328 US 293 (1946)). Rather than having three separate legislations, the Howey test could potentially provide harmonisation and a test based on the fundamental question of whether cryptocurrencies are ‘investment contracts’ ensures that ‘[f]orm is disregarded for substance and the emphasis [is] placed upon economic reality’. See Howey, 328 US 293 at 298 (1946).

Last, in light of the revelation in Crypto Conundrum Part II that both US and Europe adopt flexible regulatory approaches towards cryptocurrencies, I strongly urge MAS to consider regulatory reform, apply greater regulatory scrutiny to cryptocurrency offerings in order to increase investor protection and facilitate capital formation for cryptocurrency businesses.

Jonas Koh currently works with WongPartnership LLP.

OBLB types:

Share: