Since 25 May, 2018, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) has been directly applicable in all EU member states. Our recently published book, FinTech and Data Privacy in Germany deals with the data protection regarding FinTech services before and after the implementation of the GDPR in May 2018. The primary source of information regarding the handling of data protection of FinTechs is the privacy statements of 505 FinTech companies. We analyze the privacy statements of these FinTechs active in Germany in terms of three questions: What user data were processed? To whom were these data forwarded? And, if applicable, which third parties provided further information?

We find that a large proportion of FinTechs process personal data, and most provide this information in privacy statements. The majority also share personal data with third parties. At the same time, many FinTechs are unclear about the customer benefits that can be gained from processing these data, in the sense of big data applications, for example. However, most customers are confronted with the problem of having to accept the privacy policy in order to use the FinTech offer. Moreover, there are undoubtedly various applications of big data in the FinTech sector. However, only a few FinTechs use them in such a way that they are a critical part of the business model. One possible reason for this is that traditional financial data are already meaningful for many business models. Many FinTechs do not use big data analytics at all, though a few use big data applications, such as a credit-scoring model based on big data as a basic component of their business model. These firms are based in Germany but mainly grant loans abroad.

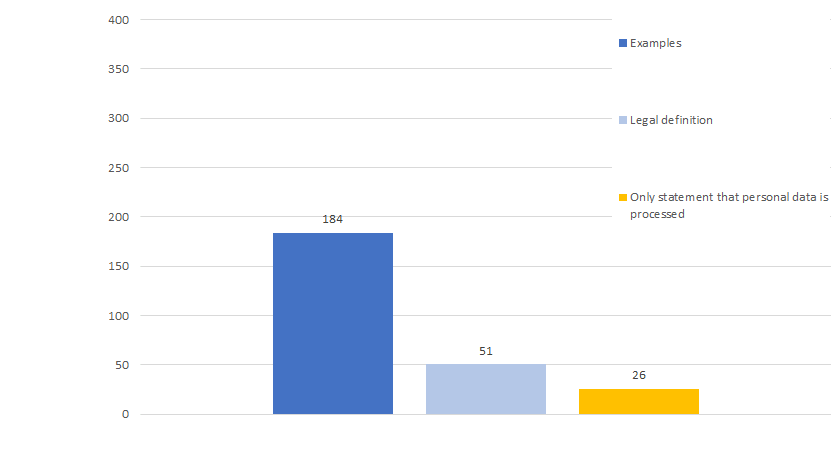

While the GDPR stipulates that information on the processing of personal user data is to be provided in a comprehensible manner, FinTech companies seldom state conclusively in their privacy statements what data are processed and with whom the data are shared. FinTech companies often limit themselves to examples or a legal definition of what personal data are. As the processed data is quite extensive in some cases and the privacy statement can become very long with a final listing, some degree of standardization could help with the presentation of the information. When using the services of third parties, FinTech companies often state that they cannot prevent the processing of data by third parties or cannot precisely determine the data processed by third parties. Instead, reference is made to the information on the websites of the respective third parties. This approach requires a major effort from users, as some companies use up to 19 web tracking and advertising services and also integrate social plug-ins. A more economical and efficient solution would be for the FinTech companies to list the data processed by third parties for users, rather than forcing each user to find out for him- or herself which third-party services are being used and what data are being processed in which way.

Figure: The reasons personal data were not listed exhaustively after the implementation of the GDPR.

Some FinTechs that initially had no privacy statements developed one after the GDPR became binding. The FinTech companies that already had a privacy statement before the GDPR became binding adapted it in four of five cases. This adaptation was accompanied by two general trends: first, privacy statements are now more than twice as comprehensive as before, and second, they now consist more of standardized text. As a consequence of the latter trend, in many areas of the statements, it is less frequently stated exhaustively what personal data are processed, what personal data are passed on to third parties, and who these third parties are. A conclusive list of this information would make it necessary to prepare the privacy statements in an individualized and nonstandardized way. FinTechs are often asked, on the one hand, to inform their users completely, but on the other hand, to inform users only briefly and concisely. It may be that only professional players can enforce the rights of numerous customers, for which the costs of enforcement are usually too high. Consumer protection associations in particular are under obligation here, and they should also be given sufficient human and financial resources to enforce the rights.

Lars Hornuf is Professor of business administration, financial services and financial technology at the University of Bremen.

Gregor Dorfleitner is a Professor at the Department of Finance at the University of Regensburg.

OBLB types:

Share: