My paper, 'Anarchy, State, and Blockchain Utopia: Rule of Law Versus Lex Cryptographia', written as a chapter of the collective book entitled General Principles and Digitalisation (Hart Publishing, forthcoming), takes the side of Robert Nozick, former Professor of Philosophy at Harvard University, in arguing that different ecosystems can coexist for the better, and applies it to the realm of fundamental rights.

The chapter shows why public permissionless blockchains constitute a separate ecosystem from the real space. Several architectural features of such blockchains make it partially a law-proof technology, or, to a certain extent, a technology that creates a space in which the law cannot be applied as it currently is. First, these blockchains ensure the privacy of their users through pseudonymity. When using blockchain platforms and services, users do not reveal their real-life identity, but instead, they show their ‘public key’ which is an encrypted identity. Second, these blockchains constitute a real barrier to enforcement because of their distributed and decentralized nature, causing them to be immutable. This inalterability applies to courts, and more generally, to public intervention: imposing to modify one copy of the ledger has no impact on the rest of the blockchain, making judicial measures mostly inoperable. Third and last, blockchains run on unstoppable code. Once potential transactions are programmed and put on such blockchains by way of smart contracts, they cannot unilaterally be modified or stopped.

For these different reasons, public permissionless blockchains create a real barrier to the Rule of Law. Of course, the Rule of Law will still apply, although partially, to all blockchain activities which involve relying on information or transactions in the real space. For instance, the selling of a car using a smart contract will imply the actual delivery of the car. The Rule of Law will then apply to this contractual obligation, but it will remain mostly inapplicable to contractual obligations realised on blockchain: in the example, transferring the money. Accordingly, there is no misconception in saying that, at the end of the day, enforcing the law on a public permissionless blockchain is more complex (and sometimes impossible) than it is outside of it. As such, if fundamental rights are being violated within such blockchains, the legal instruments generally used to address the issue will be ineffective. That is why public permissionless blockchains are sometimes called ‘a-legal’. For that reason, the Rule of Law ecosystem, outside blockchain, and the Lex Cryptographia ecosystem (defined by Primavera De Filippi and Aaron Wright as the ‘rules administered through self-executing smart contracts and decentralized autonomous organizations’), on blockchain, are meant to coexist.

My chapter then analyses the extent to which, absent the Rule of Law, users can protect their fundamental rights within the Lex Cryptographia ecosystem thanks to blockchain cryptographic architecture. The Lex Cryptographia ecosystem is not indeed an anarchy to the extent that rules, although cryptographic in nature, apply to its participants. One must study, as a consequence, how the code and design of blockchain could be used to enforce what are seen as (fundamental) rights as defined under the Rule of Law ecosystem – a ‘code as procedure’ perspective.

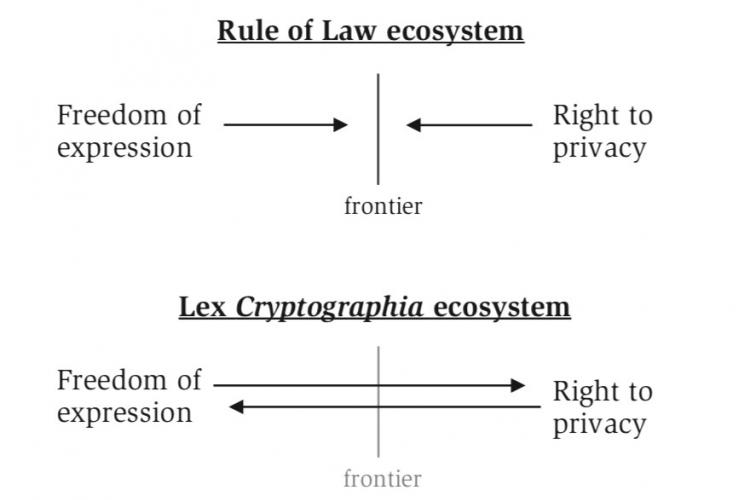

The rise of Lex Cryptographia creates a new paradigm by offering citizens, at least for part of their activities, the possibility to ‘exit’ the Rule of Law (or any other legal system imposed by the State). When they desire to do so, they will have to consider two trade-offs. The first trade-off concerns the limits put on fundamental rights. In the current state of technology, blockchain does not enable its users to claim for compensation in the event of a third user causing them some damage. There are three reasons for this. First, users’ real-life identity is kept a secret. Second, blockchain power is greatly decentralized, which forbids the taking of unilateral actions to punish users. Third and last, blockchain is immutable, which precludes the possibility of undoing eventual harms. Meanwhile, the blockchain makes the rights that are allowed by the technology almost absolute, and in so doing, creates new shocks between them. There is, differently put, a first-mover advantage as the first individual to make use of her or his rights systematically prevails over the second. For instance, when an individual #1 discloses information about an individual #2, her or his freedom of expression overrides the right to privacy. In the end, citizens may choose to use public permissionless blockchains depending on which fundamental rights they value the most, and depending on which violations to their rights they are willing to accept.

The second trade-off relates to the fact that blockchain will further highlight the acceptance by some citizens to trade certain fundamental rights in exchange for services. Numerous applications are being developed at the software layer of public permissionless blockchains. Often, their usefulness is directly linked to blockchain key characteristics. For that, the trade-off between fundamental rights and the utility derived from services will be even more visible than it is outside of blockchains.

In turn, the rise of public permissionless blockchains creates opportunities for citizens as it opens a new ecosystem with different features from the Rule of Law ecosystem. One may argue, in fact, that the coexistence of the two ecosystems will make it possible to evaluate the attachment citizens have to each of their fundamental rights. In this regard, blockchain leads to life-size experimentation of the citizens’ desire for the Rule of Law and Rousseau’s social contract as they may, for the first time, ‘exit’ rather than ‘voice’ against its malfunctioning. It would now be rather interesting to watch if States will let their citizens move freely into the Lex Cryptographia ecosystem as it would imply letting them voluntarily waive certain of their fundamental rights. At the same time, because some of States’ core functions are being replaced by the technology in the Lex Cryptographia ecosystem, one may see governmental interventions to promote the Rule of Law at the expense of the Lex Cryptographia as a way for States to protect their own ecosystem and prerogatives, rather than their citizens.

Dr. Thibault Schrepel is an Assistant Professor in Economic Law at Utrecht University School of Law and a Faculty Associate at the Berkman Center at Harvard University.

OBLB categories:

OBLB types:

Share: