The impact of bankruptcy’s public record on entrepreneurial activity: insights from economic experiments

Posted:

Time to read:

A common objective for many bankruptcy systems in developed countries is to provide a ‘fresh-start’ for the debtor. Often, this goal is seen as particularly important for entrepreneurs and those involved in small businesses — governments often want to encourage these players to re-enter the market as quickly as possible after a bankruptcy. A recent example is the Australian Government’s proposal to reduce the duration of bankruptcy to 12 months. This is designed ‘to foster entrepreneurial behaviour and to reduce the stigma associated with bankruptcy’ (see Explanatory Memorandum Bankruptcy Amendment (Enterprise Incentives) Bill 2017).

However, many jurisdictions also have a public record of bankruptcy (and other insolvency events), and the duration of public records vary. For example, in Australia and Ireland, a public record of bankruptcy is permanently available, while in England and Wales, the bankruptcy is removed from the public Individual Insolvency Register 3 months after a debtor has been discharged from bankruptcy (see section 2.2 of our paper).

The availability of public records of a bankruptcy may act as a counter to other initiatives in bankruptcy law reform that are designed to facilitate entrepreneurship. Potential business partners, providers of finance and/or investors may be reluctant to support a new business operated by a person who is or has been bankrupt, and the availability of public records may therefore make it harder for entrepreneurs and business people to re-start after bankruptcy.

Behavioural Experiment

We wanted to know more about the impact of the public record of bankruptcy, and designed an economic experiment to explore these issues in the context of previous and potential entrepreneurs and business people.

In a laboratory experiment, 138 participants either took on the role of an 'Investor' or an 'Agent'. Investors had to decide whether they wanted to invest funds in the Agent. If their decision was positive, ie an investment was made, then the Agents could decide whether they wanted to return a part of the invested funds to the Investor. Participants were tertiary students, with most participants majoring in business, economics or law.

This standardised game is commonly used in experimental economics to investigate trust and trustworthiness in strategic interactions (Berg et al 1995). In our modification of the game, Investors have access to information about the Agent’s previous return behaviour. Examining the decisions of Investors and Agents in this group, as opposed to a control group where the information was not available, enables us to determine how the availability of public records may affect decision-making. To reflect the fact that insolvency may occur as a result of a deliberate action by debtors, or because of factors beyond their control, we have built into our experiment the possibility that, with a certain probability, the game stops and the investments may be lost for both parties. The Investors, on the other side, have no way of knowing whether the Agent’s failure to return funds is due to this random shock, or due to the Agent’s decision not to return the funds.

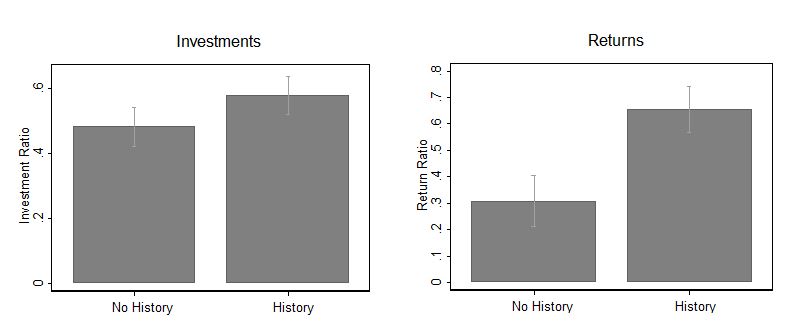

We found that investments increase when the information about the Agent’s return behaviour was available: the average investment rate was 21% higher when the records were available than when they were not. However, when the records showed that the Agent failed to return payments in the previous round, the likelihood of investment by the Investor significantly dropped, and in fact, overrode the general positive effect of public records. And the more often the returns were missed by the Agent in previous rounds, the less likely it was that the Investor would invest in that Agent.

We also looked at the impact public records have on the behaviour of Agents. The likelihood of returning payments was 120% higher when the Agent’s history of play was ‘clean’ compared with a case when the record showed a non-return in the previous round. In contrast, when the records of the Agent’s behaviour in previous rounds were not available to the Investor, the return rate did not differ depending on whether the Agent had paid back the payments in the previous round or not. This difference suggests that the availability of records motivated Agents to keep their history clean and this motivation promoted returns.

Likewise, returns by Agents were higher when the previous non-return was due to the operation of chance. When the record of past failure was, however, the result of a deliberate decision of the Agent, returns were significantly lower compared to the case when the previous return failure was due to chance or when no public records were available. We therefore conclude that a record of past failure decreased the motivation in the present round to return payments if the failure was self-inflicted, but strengthened the likelihood of a return when the past missed return is caused by an external factor.

Note: The left graph shows the average investments made in the Control group (No History) and in the Treatment group in which the public records about the history of play of each Agent were available (History). The right side of the panel shows the corresponding average returns of the Agents.

Applying these results to the case of personal insolvency, the results support our assumption that insolvency often leads to a negative stigmatization and hinders actors’ future market activities. After going bankrupt, Agents (debtors) struggle to gain back the trust of Investors. Our findings suggest that public records can facilitate investments, but benefit only Agents with a clean history. An insolvency system that has the goal of providing actors with a fresh start may need to consider how and when bankruptcy records are made publicly available, particularly if records are silent as to the market conditions faced by debtors at the time of insolvency, or the reasons for the insolvency.

However, we caution that our results are obtained from an abstract laboratory experiment with university students. Direct recommendations for law reform are therefore not possible. Rather, our study is a first attempt in trying to understand the behavioural effects of public records of insolvency. The results we obtained suggest that the availability of such records fundamentally affects the behavior of investors and debtors. Empirical work with field data could complement our findings and thus provide a sound basis for policy-making in relation to the existence and duration of public records of bankruptcy.

Nicola Howell is a Senior Lecturer in the Faculty of Law, Queensland University of Technology

Ann-Kathrin Koessler is a post-doctoral fellow at the Department of Environmental Economics, University of Osnabrueck

OBLB categories:

OBLB types:

Share: