Descriptive statistics from penality on the move. Part 1: Norwegian Penal Aid

How does penal power travel beyond the nation state? This question has concerned border criminology for some time now, which have helped uncovered various ways in which humanitarianism has been put to work on and for penal power in legitimating its transfer beyond the nation state (see themed series on ‘penal humanitarianism’). In our current research project, we have set out to map the intersections of humanitarian reason and penal governance in detail, focusing on forms of penality leaving Norway, Sweden and Denmark through development aid—indeed, as a form of ‘penal aid’ handed over to other states, societies, and citizens and as part of the ‘crime-development’ nexus. In three country-specific blog entries, we present descriptive statistics and visualizations from our datasets on Norwegian, Swedish and Danish penal aid from 1990 to 2022, focusing on ‘what’ Scandinavian penal aid is, ‘where’ it is delivered, ‘how’ it is categorized and funded, and through ‘who’, meaning, which actors are involved in this form of penal transfer.

Posted:

Time to read:

Guest post by Kjersti Lohne, Andreea Ioana Alecu and Katrine Antonsen. Kjersti Lohne is Professor and Head of Teaching and Learning at the Department of Criminology and Sociology of Law, University of Oslo, and project leader of the research project JustExports—Promoting Justice in a Time of Friction: Scandinavian Penal Exports—funded by the Research Council of Norway. Lohne is also Research Professor at the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO). Andreea Ioana Alecu is Senior Researcher at Oslo Metropolitan University and Associate Professor at the Department of Criminology and Sociology of Law, University of Oslo. Katrine Antonsen is a doctoral researcher on the JustExports-project at the Department of Criminology and Sociology of Law, University of Oslo. This is Part 1 of a three-part mini series on Scandinavian Penal Aid.

Norway is often studied comparatively through the lens of exceptionalism—whether in criminology as a representative of ‘liberal-humanitarian’ penality (but see Ugelvik and Dullum) or in development studies, where the country is often—and along with Sweden—framed as ‘humanitarian superpowers’ and ‘global samaritans’ who ‘punch above their weight’ in terms of contributions to global development goals. It is therefore especially interesting to consider how this particular Norwegian ‘brand’ of punishing humanely blends with Norway’s role in international development aid, mindful of the fact that a previous Minister of Justice (Knut Storberget) once referred to Norwegian justice personnel as ‘good Norwegian export goods’.

The Norwegian penal aid dataset is based on the Norwegian agency for development cooperation (NORAD) database on Norwegian development aid statistics and includes development aid budget registrations from 1990 to 2022. This includes penal exports, defined as models, money, personnel, institutions, laws, technologies, and epistemologies related to the complex of crime and justice. In total, 10,498 agreements are included in this dataset. Moreover, we find that the share of penal exports registrations in Norwegian development aid in total has increased from 0.49 in 1990 to 13.52 in 2022—a significant growth and an indicator of the empirical and analytical value of probing further the role of penal exports in development aid.

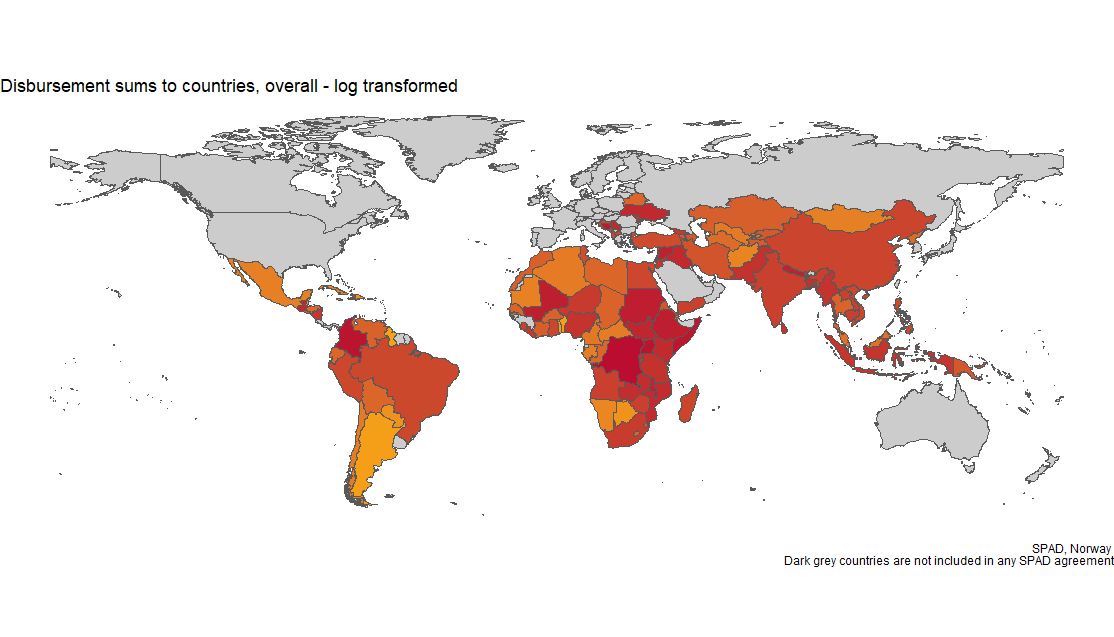

Which countries receive Norwegian penal aid?

As indicated by the map in Figure 1 above, Norwegian penal aid is delivered to almost the entire Southern hemisphere. The countries receiving the most aid include Palestine, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Uganda, Colombia, Somalia, and Bosnia-Herzegovina. In the early 1990s, Norway maintained agreements with approximately 20 countries, but by around 2005, this number had increased to over 70. By 2022, Norway had agreements with around 83 countries, showcasing its expanding global engagement.

Through which discourses do Norwegian penal aid travel?

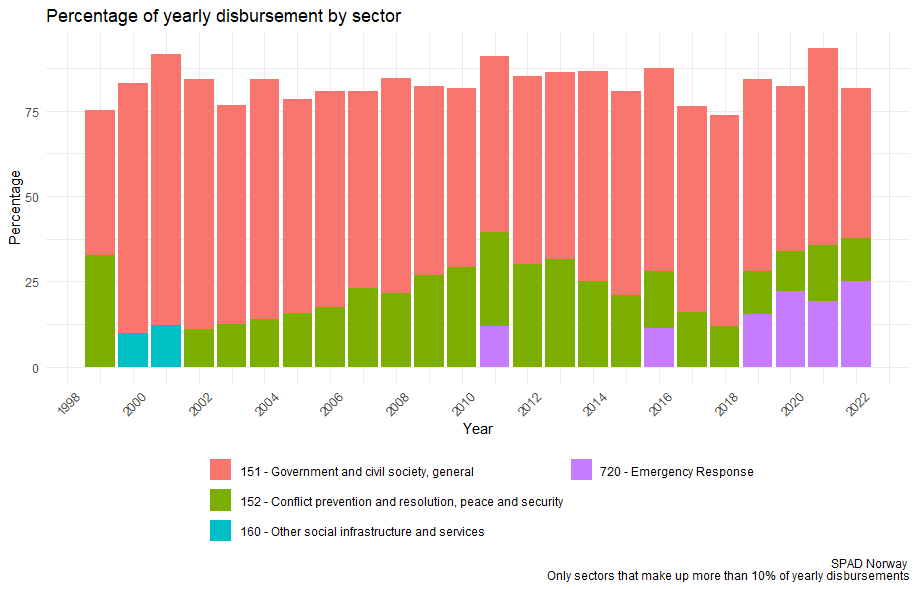

Development aid is coded and categorized in various ways, for the purposes of accountability, transparency, and reporting. In its classification system, NORAD uses OECD-DAC purpose codes (‘sector codes’) to categorize aid by the sectoral area the funding is intended to support. We see these coding practices and forms of categorization as providing unique insights into the discursive legitimation of travelling penal power.

Zooming in on how Norwegian penal aid is categorized according to sectors, Figure 2 illustrates the annual share of disbursements allocated to various sectors by Norway, and illustrates the shifts in these legitimizing discourses.

From the late 1990s onward, the category "Government and civil society, general", consistently accounted for the largest share of disbursements. This sector dominated penal aid allocations, peaking at 79.41% in 2001 and maintaining a significant share throughout the 2000s and 2010s. Furthermore, "Conflict prevention and resolution, peace and security", steadily grew in importance in the early 2010s, but by 2022 it accounted for around 12.6% of yearly disbursements. In more recent years, "Emergency Response" gained prominence, particularly during COVID-pandemic, with notable peaks of 22.26% in 2020 and 25.03% in 2022.

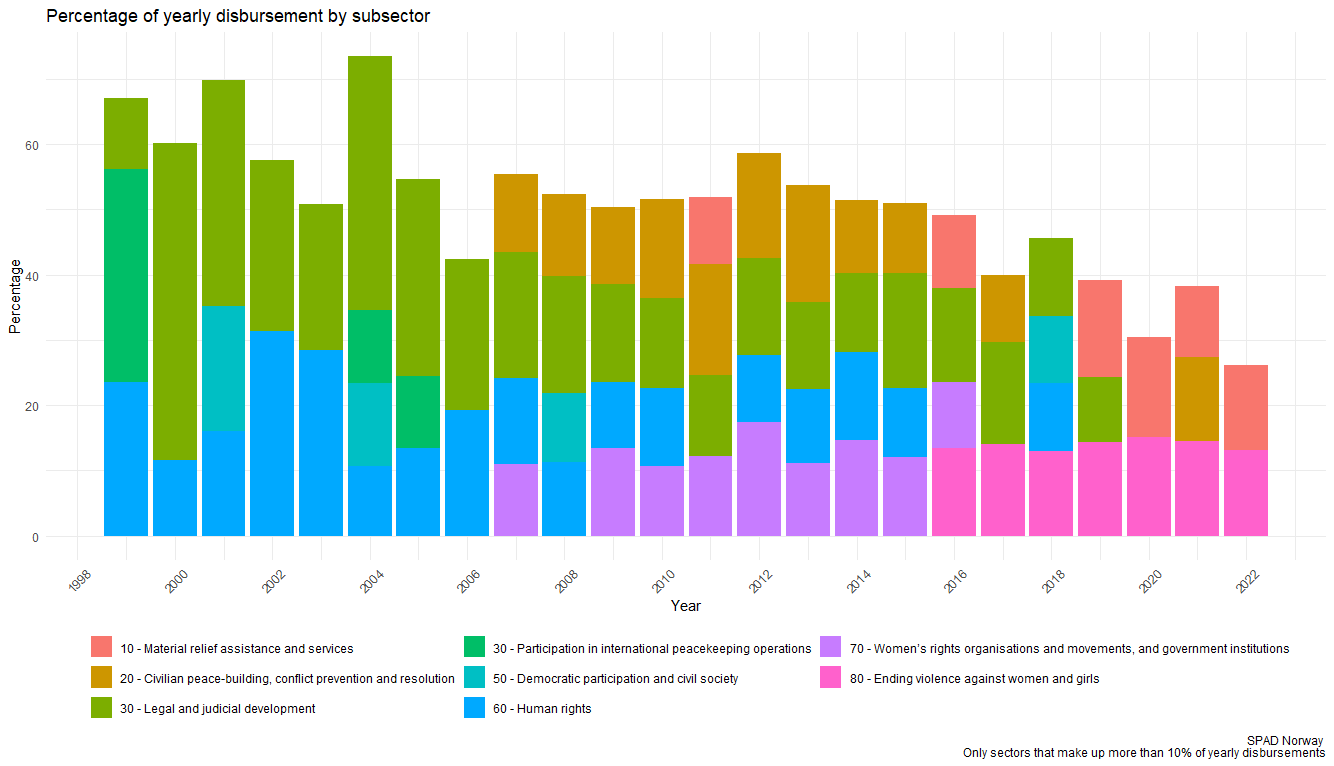

Data on sub-sector categorization provides a more detailed layer of analysis, indicated in Figure 3 below.

“Legal and judicial development” consistently received a significant share of penal aid, peaking at 48.57% in 2000 but declining in prominence in later years, stabilizing around 10–15% from 2015 onward. Human rights also featured prominently early on, reaching 31.3% in 2002, but its share tapered off in subsequent years, generally hovering around 10–13%. From the mid-2000s, “Civilian peacebuilding, conflict prevention, and resolution” steadily increased. Similarly, women’s rights organizations and movements, and government institutions gained importance, reaching a peak of 17.39% in 2012 and maintaining a steady presence around 10–15% in subsequent years. Notably, “ending violence against women and girls” became a key focus starting in 2016, with its share consistently exceeding 13% through 2022. “Humanitarian aid through material relief assistance and services” gained prominence in recent years, peaking at 15.35% in 2020 and maintaining significant shares thereafter.

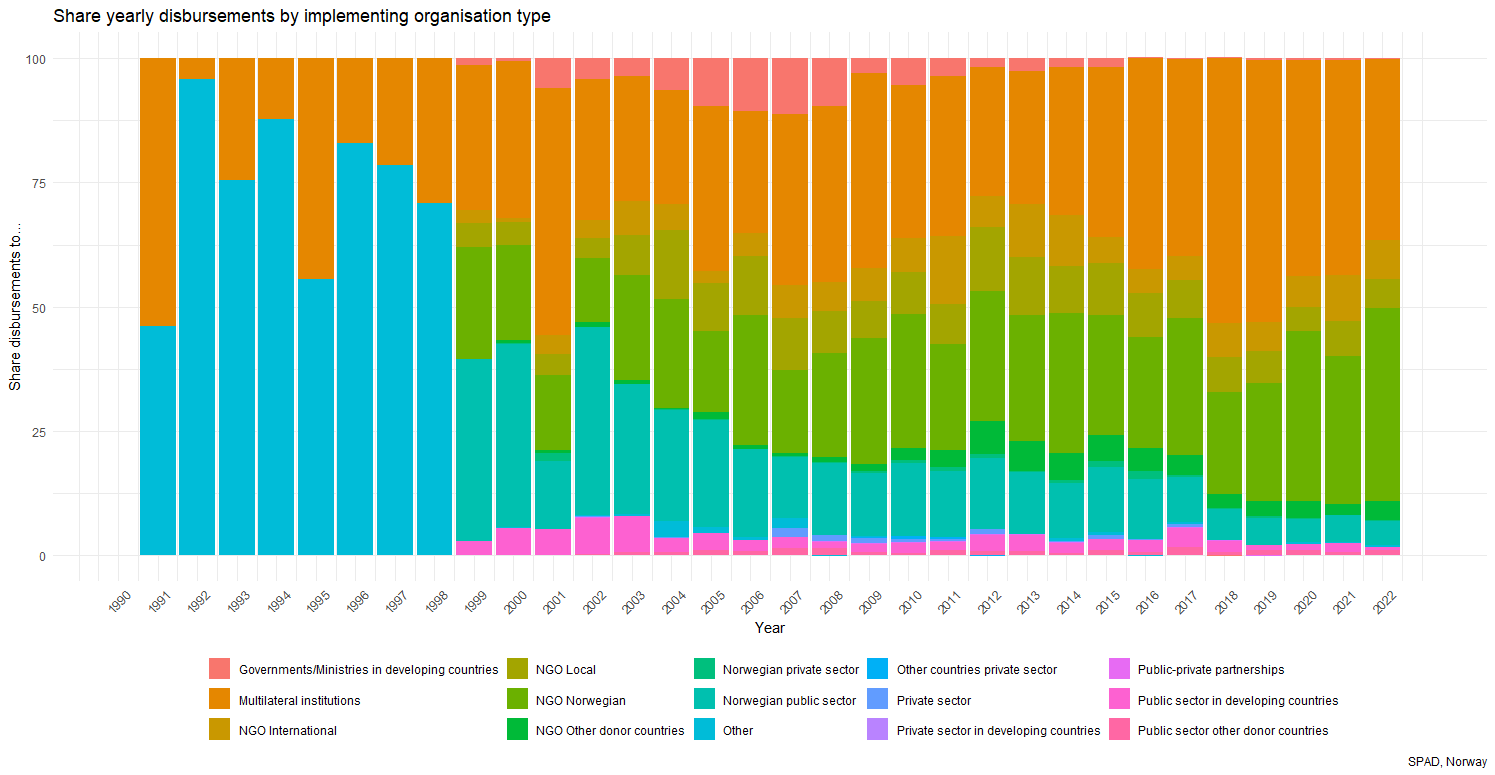

Who are the actors involved?

Different international organisations and NGOs are also involved in the field of penal aid, who are responsible for organizing and instituting projects. In the case of Norway, during this 30-year period the data reveals a strong reliance on NGOs, which collectively account for the largest share of disbursements to penal aid (43.6%). Among these, Norwegian NGOs dominate with 25.3%, followed by local NGOs (8.1%) and international NGOs (7.1%). Multilateral institutions represent the second-largest group, receiving 36.7% of disbursements, reflecting Norway’s significant engagement in global initiatives. The Norwegian public sector accounts for 11%, while the public sectors in developing countries and other donor countries collectively manage a smaller share (3%). The private sector, both domestic and international, plays a minimal role, with combined contributions below 1%. Government-to-government disbursements (2.6%) and public sector partnerships play a modest role.

Figure 4 shows the percentage of yearly disbursements to penal aid allocated to the different implementing organizations. Over time, Norwegian NGOs have consistently received the largest share of NGO-related disbursements, maintaining a dominant position and peaking at 38.8% in 2022, reflecting their central role in implementing penal aid projects. Local NGOs have played a steady but smaller role, with shares generally fluctuating between 4% and 14%, while international NGOs have shown more variability, with notable peaks such as in 2011(13.6%) and in 2021 (9.2%). NGOs from other donor countries consistently receive the smallest share, typically below 7%, but their role has grown slightly in recent years.

Multilateral institutions have also had a significant role in implementing Norwegian penal aid disbursements over time, although with considerable fluctuations. In the early 1990s, multilateral institutions received very high shares, peaking at 53.87% in 1991, followed by a sharp drop to 4.18% in 1992, reflecting potential issues with data quality at this time. From the late 1990s onward, their share stabilized at around 25–35%, with notable peaks in 2001 (49.8%) and 2018 (53.3%). In recent years, their share has averaged at around 40–50% of the yearly disbursement.

Lastly, the data shows a fluctuating trend in disbursements to governments/ministries and the public sector in developing countries, with a notable decline over time. In the early 2000s, governments/ministries received significant shares, peaking at 10.96% in 2007, but their share steadily decreased to below 1% by 2021 and 2022. Similarly, disbursements to the public sector in developing countries were higher in the early 2000s, reaching 7.26% in 2003, but have since declined to 0.68% in 2022. The private sector in developing countries consistently received minimal shares, typically below 0.1%, reflecting its limited role in penal aid implementation. This trend suggests a shift away from direct government and public sector partnerships in favor of other implementing actors, such as NGOs and multilateral institutions.

Conclusion

These descriptives provide an indication of what kind of data and analytic insights are possible from further engagement with the Scandinavian Penal Aid Dataset (SPAD), which we hope to make available open access in not too long. At a time of seismic geopolitical shifts and a decline of liberal internationalism, human rights, and development aid alike, this dataset provides a baseline for examining current and future changes to the crime-development nexus, and for discerning how (Scandinavian) penal power has expanded beyond the territorial state under the aegis of the liberal international order.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or find us on LinkedIn and BlueSky.

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style):

K. Lohne, A. I. Alecu and K. Antonsen. (2025) Descriptive statistics from penality on the move. Part 1: Norwegian Penal Aid . Available at:https://blogs.law.ox.ac.uk/border-criminologies-blog/blog-post/2025/11/descriptive-statistics-penality-move-part-1-norwegian. Accessed on: 24/02/2026Share: