Using Vulnerability-Centred Health Assessment as a Tool for the Differential (De)Valuing of Human Life: The Case of Italian ‘Illegal Decrees’ for Selective Sea Rescues

Posted

Time to read

Guest post by Chiara Denaro and Francesca Esposito. Chiara is a Postdoctoral researcher in Sociology at Trento University on the project “PRIN-2017, Debordering activities and citizenship from below of asylum seekers in Italy”. She is a social worker and legal expert, working with migrants and refugees. Her socio-legal research work concerns asylum and migration policies in the Mediterranean space, border control policies, human rights, right to asylum, as well as the practices and strategies of resistance put in place by people on the move. As part of WatchTheMed Alarm Phone, Chiara focuses on the Central Mediterranean route. Francesca is an Associate Director of Community Engagement and Activism for Border Criminologies and her research focuses on border control and immigration detention in Italy, Portugal and the UK.

Between the end of October and the beginning of November 2022, four civil society organisations (Sos Humanity, Doctors Without Borders, Mission Lifeline and Sos Mediterranée) involved in Search And Rescue (SAR) activities rescued more than 1,000 people in distress in the Central Mediterranean. After these rescue operations, the ships Humanity 1 (NGO Sos Humanity, 179 survivors), Geo Barents (Doctors Without Borders (MSF), 572 survivors), Rise Above (NGO Mission Lifeline, 89 survivors) and Ocean Viking (NGO Sos Mediterranée, 234 survivors) were left in standoff for several days, due to the refusal of the Italian government to assign a Place of Safety (POS), where people could have been safely disembarked and rescue operations concluded.

Beyond the general mainstream narrative which again, like in 2017, depicted NGOs as “illegitimate” actors, colluding with smugglers, being a pull factor, and not operating “in line with the spirit of EU and Italian norms concerning security, border control and contrast to illegal immigration”, the approach by the recently elected far-right Italian government was quite blurry and contradictory. While two of the four civil rescue ships (Humanity 1 and Geo Barents) were targeted with an interministerial decree (signed by the Ministers of the Interior, of Defence, and of Sustainable Infrastructure and Mobility) and ordered to leave Catania’s port after completing a “selective disembarkation” procedure, one ship (Rise Above) was authorised to disembark all the survivors in Reggio Calabria. The remaining one (Ocean Viking) decided to head to France, after unsuccessfully sending more than 45 POS requests to Italian authorities. The manifest contradictions of the provisions included in the above-mentioned interministerial decree with international maritime law, human rights law, and asylum law resulted in it being labelled as “the illegal decree”.

Building upon these criticisms, in this post, we examine the instrumental use of state-sanctioned notions of ‘vulnerability’ and related bio-medical health assessments as a key bordering tool to sustain the differential (de)valuing of human life. Several scholars have outlined how vulnerability has become a selection and filtering tool in hotspots and other border zones (see, for instance, here, here and here), as well as a weapon in the hands of policy makers and officers who work in the design and enforcement of border regimes. On the other hand, vulnerability has been also appropriated and strategically used by those opposing and challenging the violence of borders (see, for instance, here and here). The instrumental use of vulnerability and public health issues by the Italian government, however, seems in this case to go far beyond the procedures applied in the past, also signalling a move towards the increasing outsourcing of border enforcement to third parties (i.e., healthcare personnel and, more recently, civil society crews involved in SAR activities). This process goes hand in hand with the repeated, but until now failed, attempts by the Italian state to externalise its obligations to guarantee international protection to people on the move (e.g., by trying to shift this responsibility to flag states of rescue vessels).

Against this backdrop, this post sheds light on the strategic use by the Italian state of vulnerability-centred health assessments as a key border management tool which pushes healthcare staff into becoming border enforcers. Yet, on the other hand, we also highlight the resistance put in place by survivors on board, by the SAR NGOs themselves, and also by doctors and psychologists, which ultimately resulted in all people being able to disembark.

The Italian “illegal decree(s)”

After two verbal notes issued to the Humanity 1 and Geo Barents, and a first directive by the Ministry of Interior referring to those notes (24.10.22, prot. 0070326) and asking flag states of rescue vessels (respectively Germany and Norway) to take responsibility for indicating a safe harbour, two identical decrees were issued by the Ministry of Interior, of Defence and of Sustainable Infrastructure and Mobility on the 04 November 2022. These latter ordered the two civil rescue ships to reach the port of Catania to perform a 'selective disembarkation procedure'.

Particularly, the interministerial decrees received by Sos Humanity and MSF indicated that the ships were “prohibited from stopping in national territorial waters beyond the time necessary to ensure rescue and assistance operations for people in emergency conditions and in precarious health conditions reported by the competent national authorities.” They also added that “[i]n any case, all the people who remain on the boat will be assured of the necessary assistance for exiting territorial waters.”

The illegitimacy of this provision, rightly defined by human rights advocates as the ‘illegal decree’, lies in several aspects: i) it does not allow the completion of the rescue, through the disembarkation of all the survivors in a place of safety, by violating the law of the sea (2004 SAR and SOLAS Conventions amendments, see Farahat and Markard); ii) it requires the exit from territorial waters of those who “remained on the boat” - because they were not found in “emergency conditions and precarious health conditions” as reported by competent national authorities” – thereby resulting in a collective expulsion, which is forbidden by international human rights and asylum law.

This development evidently signals a detachment between the international legal framework of the law of the sea, human rights and asylum, and provisions included in “soft law instruments”, such as this decree. Such a disregard for international law is however not new and needs to be read in continuity with previous events, such as, for instance, the Italy-Libya memorandum of understanding as well as the so-called “closed harbour” and “unsafe harbour” strategies.

Sorting out those who are “not sick enough”

From an operational perspective, the issuance of these interministerial decrees led to a partial disembarkation of people rescued by Humanity 1 and Geo Barens: after disembarking minors and women, those who are usually considered vulnerable par excellence, the Italian health authority for maritime and air borders (USMAF) performed a discretionary assessment of health conditions for those remaining onboard. As a result of this bio-medical assessment, respectively 36 and 215 people were not authorised to disembark, and the two ships were ordered to leave the port of Catania with them onboard.

As reported by the Sos Humanity Head of Mission to one of the authors (Chiara):

When we moored, everything looked normal. The Red Cross was there, UNHCR was there, Save the children, Frontex, Police, Guardia di Finanza were all there. It was a normal disembarkation from the outside. After we moored, the Usmaf came onboard. They basically took the temperature of two persons and then started straight away the disembarkation. Basically 5 min after we moored, they took women and babies, and then all the unaccompanied minors without asking anything. It was quite quick, one by one, and then… you could really feel the change as soon as it was coming to the [male] adults. The doctors came onboard again, they went into our clinic and they did a one on one examinations on the [male] adults, everyone who was not sick enough for them to become, to become… a medical case was sorted out, put back on deck.

[…] Another doctor came onboard, and the people needed to go through the whole procedure again, one by one, medical examinations, but that did not change anything. We still have 35 people onboard (Sos Humanity, Head of Mission).

This testimony sheds light on how vulnerability-centred health assessments are increasingly becoming the new parameter to define the unequal distribution of life chances organised around race, gender, class, and citizenship status (on the state-sanctioned production of group-differentiated vulnerabilities to premature death, see Gilmore). It also shows, as recently argued by Barbara Pinelli, the shift from a logic of “women and children first” to that of “women and children [and sick – our addition] only”.

Adult men who ‘were not considered to be sick enough’ were simply left out. In other words, being considered in a ‘good health’ – based on state-defined bio-medical criteria – meant losing access to fundamental rights, such as that of being disembarked in a place of safety after being rescued; entering Italy and accessing the asylum procedure; not being collectively pushed back and exposed to violence, torture, and risk of premature death. In this process, the national health authority for maritime and air borders (USMAF) was turned into a de facto border enforcement agency, with the discretionary power to select those who could disembark, and live, from those who could not, therefore being left to face the risk of death. According to more than 200 Italian doctors – who signed an appeal to the medical association – this development clearly violated the Medical Code of Conduct.

“I won’t move from here, until all the people we have on board will be disembarked” (Sos Humanity, Head of Mission)

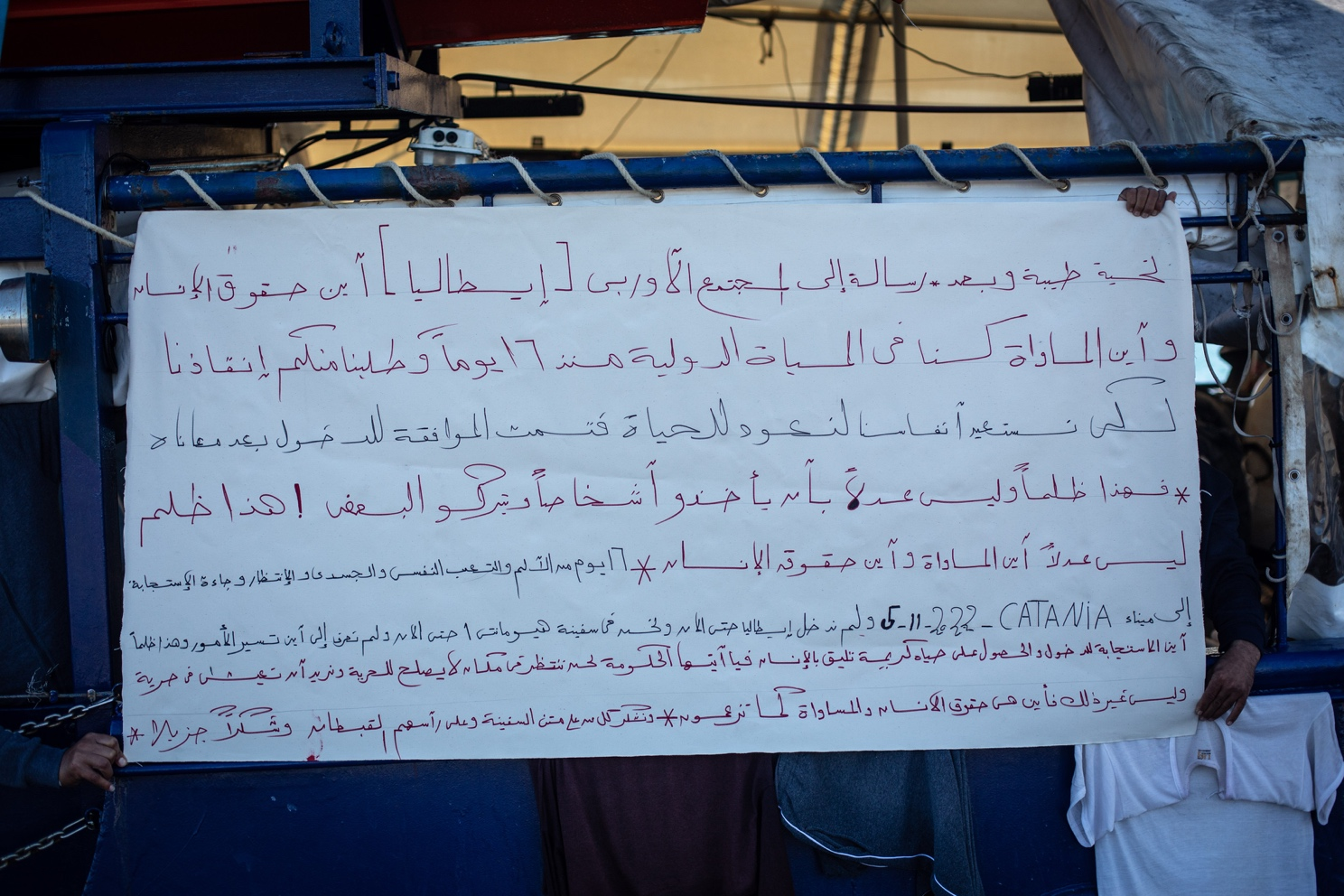

After the enactment by the Italian government of the ‘illegal’ orders for NGOs to leave Catania port after completing the selective disembarkation operations, several actors challenged the decision. To strongly denounce the illegitimacy of what was happening, different tools and approaches were adopted: from protests by survivors onboard; to acts of civil disobedience by the civil rescue crews; to permanent sit-ins in Catania, Rome, and several other Italian cities, asking for everyone’s disembarkation. “Civil disobedience is the only response to cruel, illegitimate and illegal orders by Italian state authorities!” wrote Alarm Phone activists in a tweet, showing solidarity to NGOs.

MSF and Sos Humanity decided to disobey the order to leave the port of Catania, despite being threatened to receive a €50,000 fine, while the survivors on board started protests and a hunger strike, and three of them jumped overboard. In the meantime, doctors and psychologists’ professional orders and associations launched different campaigns denouncing the actions of the USMAF as in violation of professional ethical codes. Citizens and activists, on their side, organised a permanent assembly at the port in solidarity with people detained onboard and civil society organisations resisting the Italian government’s order to leave. These acts of resistance and solidarity were eventually successful, and, following a clinical assessment by the local mental health service team, everyone one on board was able to disembark. However, the plans of the far-right Italian government currently in power will not be easily overturned, and it is likely we will see this happen again in the near future. In fact, very recently the Italian Council of Ministers approved a decree that introduces new and more stringent rules for SAR activities conducted by civil society organisations. As expressed by civil society groups engaged in SAR operations, the new decree “obstructs lifesaving efforts at sea and will cause more death”, by strategically attempting to limit their rescue activities. This is done, in practice, by assigning distant ports and instructing NGOs ships to proceed to them immediately (therefore preventing multiple rescue missions to take place). Yet as AOI and ASGI have underlined, also calling Italian MPs to oppose the decree conversion into Law, some of these new provisions are in open contrast with international maritime law, human right law and the European and domestic legal framework on asylum – and therefore de facto unrealisable. The Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights, Dunja Mijatović, has also recently expressed serious concerns about this measure.

Creating cracks in border infrastructures

We have witnessed elsewhere the devastating impacts of hostile environment policies designed to sustain the differential (de)valuing of human life, by also outsourcing border control to third parties. Yet, we have also witnessed, over the years, important actions of bottom-up resistance and solidarity, defying state-sanctioned violence against the movement of the global poor and racially undesirable. These actions, individual and collective, have been harshly criminalised, particularly when put in place by people on the move themselves. Still important struggles have been won, including in Court rooms, creating cracks in the infrastructure of border regimes. This is the case also of the recent decision by the Civil Court of Catania, which establishes that the interministerial decree issued against the Humanity 1 on 04 November 2022 was unlawful as “it discriminatorily hindered the right to rescue and access to the asylum procedure”. This decision is highly relevant to all those involved in the struggle for freedom of movement and against border violence, in Italy as elsewhere. It is particularly important in light of the discussion that will take place next week in the Italian Parliament, when the law decree of 2 January 2023, also known as ‘anti-rescue decree’, will be voted by MPs. In fact, it highlights the international obligation of Italy to assist people in distress at sea and underlines that rescue operations can only be considered concluded when survivors are disembarked in a Place of Safety.

Vulnerability and its state-sanctioned definition and assessment, as this blog shows, is increasingly becoming a key technology to sustain a differential (de)valuing of human life, and therefore a crucial terrain of political struggle. As argued by Bridget Anderson, Nandita Sharma and Cynthia Wright in a brilliant piece published more than a decade ago, “(...) the problem with the language of protection and harm is that it inscribes the state as an appropriate protector for vulnerable migrants”. The scholars explain that what is at stake is the construction of particular groups of people as intrinsically/naturally vulnerable, thereby obscuring the state's production of vulnerability through immigration controls and its use to create, maintain, and strengthen relationships of power and subjugation. A political project that aims to challenge border regimes and their violence cannot, therefore, disregard this evidence. Instead, it is only by contesting, inside and outside courtrooms, the state production of these hierarchies of deservingness, and by unveiling the role played by regimes of vulnerability (and dangerousness) in sanctioning a differential value for human lives, that we can effectively dismantle this system, ‘brick by brick, law by law’.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style):

C. Denaro and F. Esposito. (2023) Using Vulnerability-Centred Health Assessment as a Tool for the Differential (De)Valuing of Human Life: The Case of Italian ‘Illegal Decrees’ for Selective Sea Rescues. Available at:https://blogs.law.ox.ac.uk/border-criminologies-blog/blog-post/2023/02/using-vulnerability-centred-health-assessment-tool. Accessed on: 19/04/2024Keywords:

Share

YOU MAY ALSO BE INTERESTED IN

With the support of