Guest post by Maria De Angelis, senior lecturer and independent researcher at Leeds Beckett University. Maria is an active member of CIRN: the Centre for Interdisciplinary Research in Narrative at St. Thomas’ University in Canada, and of the Women, Crime, and Criminal Justice Network (British Society of Criminology). Maria’s interest is in art as socially engaged practice and affective pedagogy. A current example of her work is the ‘Seeing Asylum’ exhibition showing, in 2022, as part of the Leeds Literary Festival in March and Refugee Week in June.

The photo-boards (three of which are displayed below) visualise, in their own words, the lived experiences of fifteen asylum seekers living in the city of Leeds, all of whom spent time inside a British Immigration Removal Centre (IRC). For women with incomplete or missing papers, an active border machine rules every aspect of daily life– affecting housing, health, education, advocacy, banking services and work, under the overarching threat of indefinite detention in a secure facility until they can be deported. ‘Seeing Asylum’ sought to apply a relational lens on women’s agency in these two contexts of immigration-related trauma and struggle, one inside detention walls and the other outside in a community setting. Local charities helped source the call for volunteers to share stories of a good and a bad day in detention, and a pivotal moment in their dispersal to a community.

The exhibition’s primary objective of public engagement with the British system of asylum administration was easily agreed on. The women who volunteered their stories did so in hope of a better legal-policy-community reception for future asylum seekers. Crossing a border may not be a crime, but deaths in the English Chanel, the criminalisation of migration, sanctions on those who assist them, and welfare support below the poorest 10% of British citizens, reflect an ‘everyday racialized bordering’ between citizen and non-citizen.

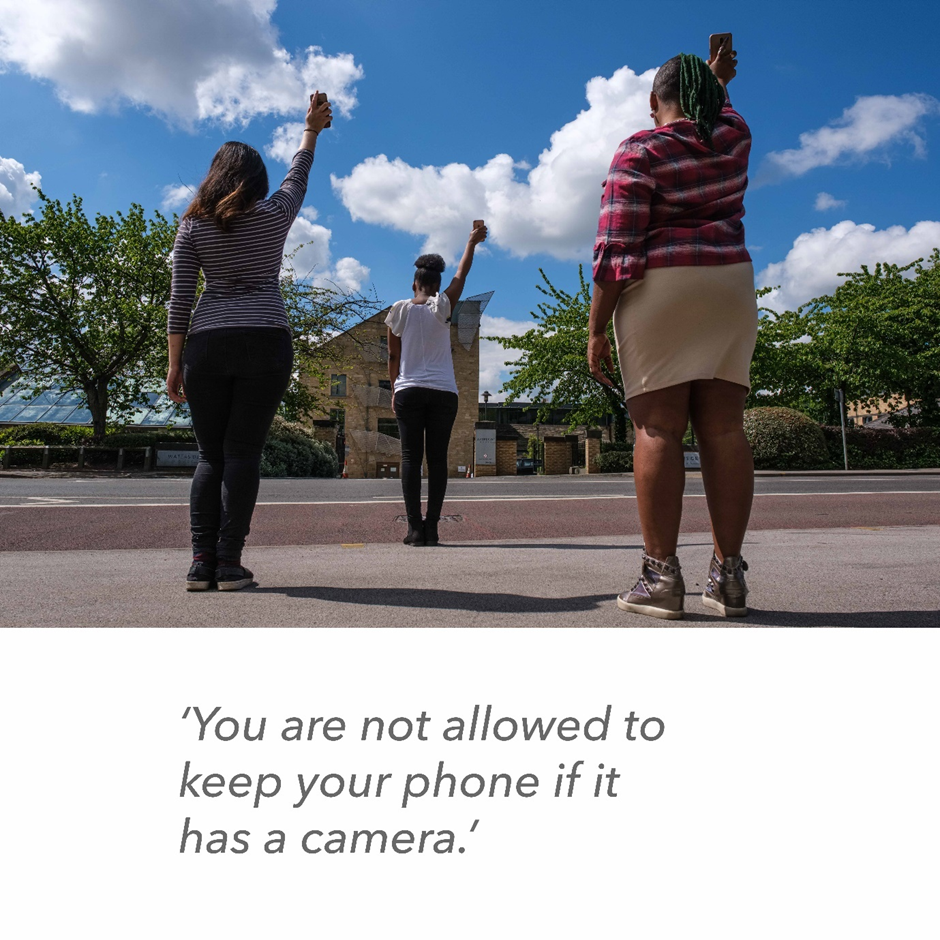

Set against this overriding objective, the artistry of visualising women’s stories proved more of a challenge. Since women cannot take photos inside an IRC and feared repercussions to their ongoing claims if identified as speaking out, the actors in the photo-boards are a mix of students and colleagues from Leeds Beckett University and critical friends. The decisions over which experiences to prioritise and how to represent them were a negotiation between the women, researcher, associate photographer, and critical friends from local charities.

Of course, the eleven photo-stories cannot fully or definitively express what individual life is like inside a British IRC, or post-release into a community. But when art makes visible the voices, stories, and experiences diminished by an uneven and imposing border machine, it starts an activistic conversation with taken-for-granted narratives of race, asylum, and migration control. As a collection, the ‘Seeing Asylum’ photo-stories privilege counter standpoints towards the structures that oppress them, as in their modern slavery typologies, the illegitimacy women attach to their detainee status, or their indignation of carceral practices captured in the photo-board below.

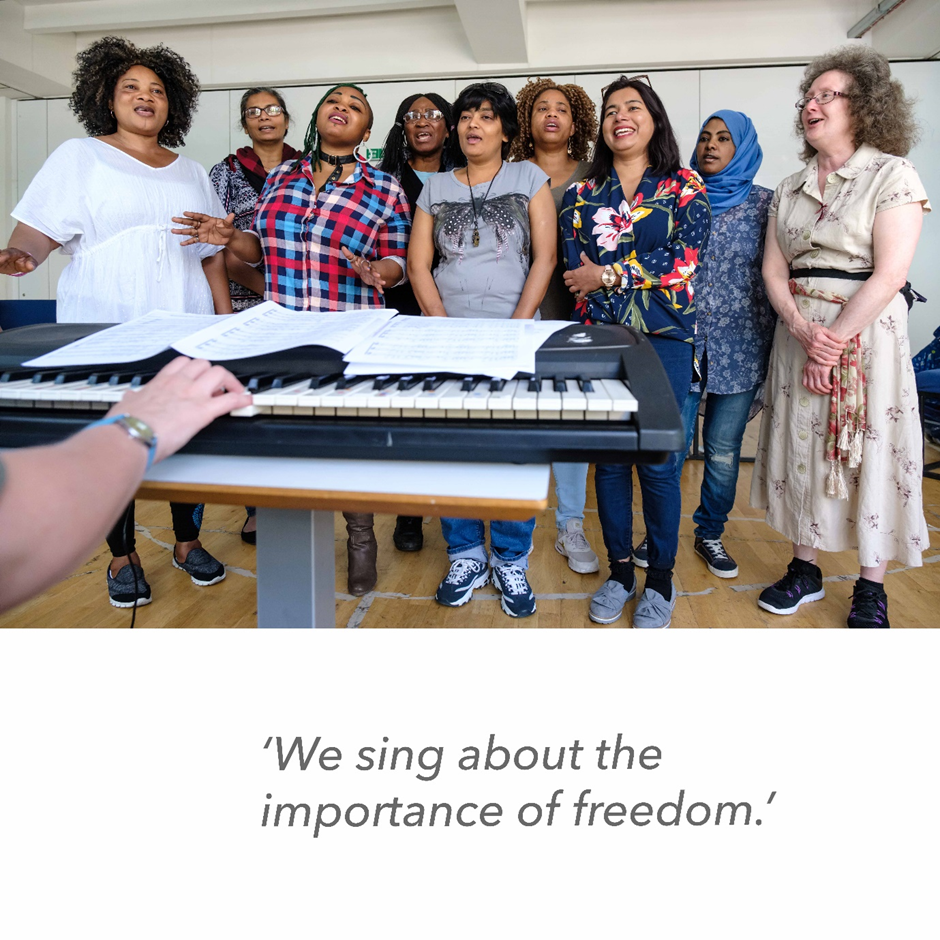

As individual photo-stories, each captures a single moment of emotion, protest or belonging, channelling the reader’s gaze towards alternate epistemologies, for example, around identity and belonging. As Hughes observes in her research with the charity Music in Detention, making music together constitutes a point of intersectionality. When a culturally diverse band of people add their indigenous beats to music, it has the power to simultaneously express their different cultures and unite them in rhythm. The uniting force of rhythm is visible in Sita’s story-board (25 from Ivory Coast) below, where culturally disparate choir members harmonise in songs of freedom.

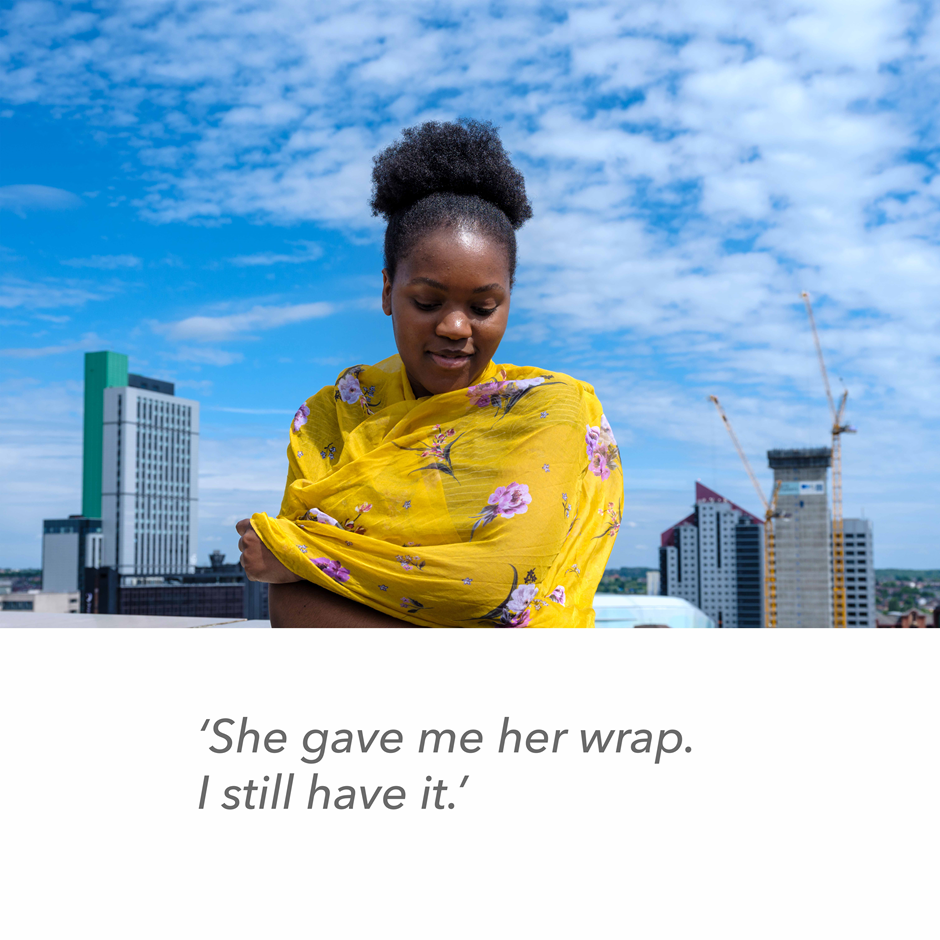

Kia’s story-board (41 from Uganda) below, provides the reader with an alternate epistemology on identity to the one discursively constructed by officials in authority. Kia tells the story of her first day in detention: ‘The first lady I shared with, I think she was from Russia and the way they arrested me, I didn’t have anything with me, and she gave me her wrap. I still have it. I don’t want to throw it away. She was asking for a flight. But they play evil tricks with you. When people want to go back, they don’t send them back’. To Kia, this singular human gesture signifies rejection of a long-standing and dehumanising immigration philosophy which reifies her (and other migratory or displaced persons) as a deportable body, and little else besides.

Shifting gaze back to the project objective, if the activistic nature of exhibition rests on the belief that inhabiting the experience of asylum seekers can impact the visitor, then as Petersen concludes, critical art (in all its genres) needs an audience ‘to see, experience, and conceive the world differently’ in order to be activistic in tone and reach. As ‘Seeing Asylum’ takes its audience on an experiential tour of lived asylum realities, it opens experience out to narratives other than our own and becomes an interactive process in how we perceive ourselves against the other. In this spirit of public engagement, women and critical friends invite us to anchor these tales of lived experience into our daily conversations and our respective fields of influence.

A fuller account of stories featured in the exhibition can be accessed here.

Acknowledgements

Heartfelt thanks go to the fifteen remarkable women who shared their asylum stories. Thanks also go to Critical Friends at City of Sanctuary; Refugee Education Training Advice Service (RETAS); Toast-Love-Coffee café; Asmarina Voices; Hinsley Hall; Universities Chaplaincy in Leeds; and Leeds Church Institute (LCI). Particular thanks are owed to Jeremy Abrahams – associate photographer. The research is funded by the Centre for Applied Social Research (CeASR) at Leeds Beckett University and generously hosted by the LCI.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style)

De Angelis, M. (2022) Seeing Asylum in Tales of Lived Experience. Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2022/03/seeing-asylum [date]