‘Hypervulnerability’ Through Adapted Asylum Procedures During Covid-19 In Belgium

Posted:

Time to read:

Guest post by Lukas Kestens. Lukas graduated from the Ghent University (Belgium) in Conflict and Development Studies with a research focus on migration issues. With a PhD-candidacy in mind, he is currently active with Caritas International (Brussels) as project associate for Community Sponsorship. In this post, Lukas discusses the procedural flaws of the asylum registration model in Belgium, with a focus on the extraordinary measures implemented during the Covid-19 pandemic and beyond. This is the fifth post in Border Criminologies themed series on'Everyday Violence and Resistance in Europe’s ‘Migration Management’ During the Covid-19 Pandemic', organised by Marta Welander and Dr Susanne Jaspars.

Adapted asylum registration in Belgium during the Covid-19 pandemic

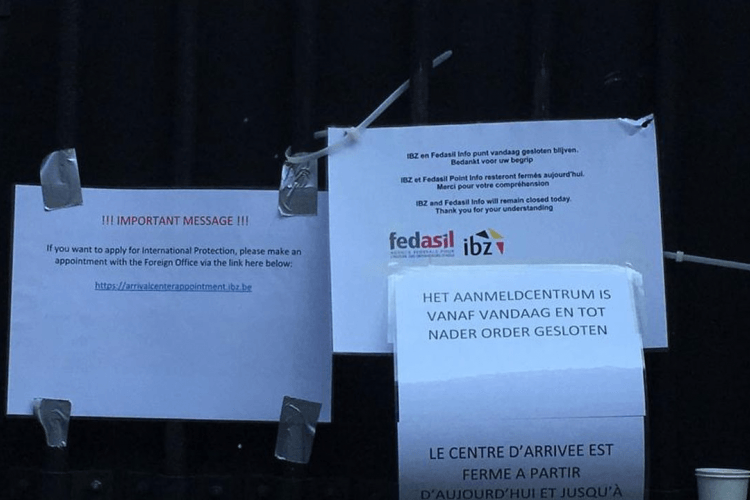

When Covid-19 spread across the European continent mid-March 2020, it brought with it new complications for people on the move, who in addition to acute health risks also faced additional legal hurdles. Registration and reception of asylum seekers ceased to be a priority to many EU member states. With national lockdowns announced across the continent and member states closing their borders, they either resorted to online or digital alternatives to ensure (partial) continuation of asylum registrations (e.g., Germany, the Netherlands) or suspended them altogether (e.g., France, Greece). Meanwhile, in Belgium, the doors of the arrival centre ‘Little Castle’ in Brussels were closed and an ‘interim’, online pre-registration procedure was introduced in early April 2020. This new procedure was initially justified by the need for federal asylum authorities to process asylum registration in a ‘safe and structured manner’. Yet, the contrary happened and, as a result, hundreds of asylum seekers were left on the streets without registration nor shelter. Media coverage and worrying reports from the few civil and ‘frontline’ actors still operational despite the pandemic, sparked interest in investigating and analysing the issue more in-depth.

By chronologically reconstructing the events during this period, we have discovered the impact of the introduction of this interim ‘solution’ in Belgium on people on the move, as well as state and civil actors involved. We also established how digitalisation gave rise to new dynamics, problems and (improvised) solutions. Over a year and a half later, the online pre-registration procedure is now history, yet the question is: for how long?

Introducing an online pre-registration procedure

The best way to describe this ‘interim’ asylum registration process is to call it an “online pre-registration procedure”. This name fully grasps its meaning as a ‘mere’ online, remote steppingstone towards one’s actual asylum registration. For newly arriving asylum seekers, it was obligatory to complete their pre-registration online, in order to initiate their asylum procedure. Specifically, this meant that they had to (1) complete an online form with personal data, photos and scanned documents, as well as (2) attend a physical registration appointment as specified by a confirmation email. Although intended as a temporary solution, the practical, digital specificities of the interim procedure proved in reality a temporary hurdle for (many) asylum seekers. Compared to the ‘normal’ asylum procedure, this ‘interim’ approach thus added an additional online aspect to the process; something that affected the positions of both asylum seekers as civil society organisations at the ‘frontline’.

Vulnerabilising the excluded even more

The interim procedure’s requirements, in terms of linguistic, social and (digital) material aspects, proved too demanding for some asylum seekers, as the online form was only available in Dutch and French, and its completion required access to the internet, a laptop, mobile phone, scanner and/or printer. For those without the necessary resources to access the pre-registration and, for example, include photos and scanned documents, no support or information was provided by the government. As such, those unable to complete their pre-registration ended up in a grey area of being unregistered and without a shelter, yet in need of protection. Even for those who managed to pre-register, their confirmation email could be delayed for weeks and, in some cases, even months, while day and night shelters in Brussels quickly reached their maximal (and decreased due to Covid-19) capacity. Simultaneously, very little information was available to explain the system and the reason for the increased waiting times. This proved especially problematic for asylum seekers without a support network in Brussels or Belgium. Left to their fate, many relied on a small number of civil society organisations to complete their pre-registration. Most civil actors, however, also lacked information on the interim procedure’s practicalities and therefore saw no other option than engaging in improvised, trial-and-error support. This included managing people’s pre-registrations themselves, exchanging asylum seekers’ personal data to follow-up on their procedures and creating email accounts and passwords for those without one. In hindsight, such humanitarian support inadvertently turned out to be rather ambivalent, unwillingly legitimising and prolonging the existence of the ‘interim’ procedure while also stripping asylum seekers from the control over their own (digital) personal data and procedure.

Inspired by the work of Walters and Pallister-Wilkins, this environment for asylum seekers could be defined as a humanitarian borderland, where people seeking asylum are dependent on, and entangled in both the life-saving operations by civil society actors and the repressive measures by state authorities. Of course, the online pre-registration procedure didn’t affect all asylum seekers evenly. While it proved trouble-free for some, yet troublesome for others, the ‘interim’ procedure worked as a kind of differentiator between different asylum-seeking profiles. Typically for asylum procedures, women, children and other vulnerable individuals were prioritised, while single men remained last in line. As a result, the non-prioritisation of these men rendered them exposed to increased vulnerability and precarity, subjected to a type of state violence that Welander and Ansems de Vries have called ‘politics of exhaustion’, marked by a long-lasting period of uncertainty, violence and hardship. As such, a part of ‘vulnerabilised’ asylum seekers was not taken care of, were it not by civil society, and thus confronted with a kind of ‘hypervulnerability’.

Looking ahead: different crises, similar problems, new solutions?

As this example from Belgium shows, digitalising asylum procedures has very real consequences and effects. The digital requirements create additional, invisible yet real obstacles for people seeking asylum and limit their right to seek protection. The burden of digitalisation accompanied by a lack of information, helpdesks or explanatory tools results in weakening certain asylum seekers’ access to the procedure, where those lacking certain skills and capacities are singled out and worse off, as well as in exposing people to increased vulnerability and dependency on civil society support. This would further reduce the level of control and oversight each individual has into their asylum procedure, a potentially life-changing process, as civil society would now organise pre-registrations for hundreds of people by logging in on their email accounts, creating new accounts, and so on.

Therefore, in the event that digitalisation of asylum procedures becomes an inevitable reality, it must under all circumstances go hand in hand with assistance and information frameworks to give people on the move a fair and equal chance to seek international protection. This plea for better support towards asylum seekers goes beyond the context of the first months of the pandemic and also applies to what is happening today. From September to December 2021, Belgium reported another ‘reception crisis’. While the entire reception network seemed overcrowded, hundreds of asylum seekers were refused registration and shelter. Even with no online pre-registration procedure in place, the outcome is similar – asylum seekers on the streets, hindered to access the procedure and increasingly depending on civil society’s support to survive. This continuation of a failing process will likely contribute towards more structural problems in the way asylum registration and reception are set up.

The absence of pre-reception support and/or assistance and the lack of structural and necessary cooperation between state and civil society actors has become apparent. As long as these dynamics continue, any kind of ‘innovative’ asylum procedure – for example by digitalisation - is likely to reach its target group only partially, benefitting the already ‘capable’ and harming the majority of those with lack of resources. This, of course, risks leaving many more people on the move trapped in harmful, often urban environments and legal limbo over the coming months, and needs to be called out along with a strong demand for the fundamental rights of people seeking protection in Europe to be upheld.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style)

Kestens, L. (2022) ‘Hypervulnerability’ Through Adapted Asylum Procedures During Covid-19 In Belgium. Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2022/03/ [date]

Share: