Guest post by Erlend Paasche. Erlend is a senior researcher and sociologist who is specialized in migration studies. He works at the Norwegian Institute for Social Research, where he coordinates the project Deporting Foreigners: Contested Norms in International Practice (2021-2024). Disclosure: Erlend gave input to the European Commission on the Strategy discussed in this post.

There is an abundance of criminological studies of deportation but few have explored the so-called ‘Assisted Voluntary Return programmes’ (AVRs). Yet both deportation and AVR are central to European immigration law enforcement. AVRs typically provide assistance with acquiring travel documents and organize return flights free of charge. Funded by host states and implemented by service-providers such as the International Organization for Migration or non-governmental organisations, they also offer cash grants upon return, or some form of in-kind reintegration support, or a combination thereof.

Sociologists have analysed AVR as ‘soft deportation’, indicating the absence of brute force but also acknowledging the inherently coercive nature of return for those ordered to leave, and the hostile environment in which it occurs. Why, then, are criminologists not more interested?

Perhaps the study of deportation, being ‘lived’ as punishment by deportees but not legally defined as such by states, is quietly considered audacious enough, stretching the discipline of criminology beyond its home turf of criminal justice? More provocatively, could it be that the criminological gaze has been skillfully diverted by that strategically crafted misnomer, ‘voluntary’?

A recent policy development suggests that criminologists may need to reconsider their priorities. In April 2021 the European Commission launched the first-ever Strategy on Assisted Voluntary Return. It presents a mixture of old and new elements, that need to be carefully unpacked.

The Strategy reaffirms the EU’s commitment to what it habitually refers to as a ‘more effective, humane and orderly return’, while acknowledging that uptake remains far below desirable levels.

Commissioner for Home Affairs, Ylva Johansson, sums up the rhetoric in her presentation of the Strategy.

Only about a third of people with no right to stay in the EU return to their country of origin and of those who do, fewer than 30 per cent do so voluntarily. Voluntary returns are always the better option: they put the individual at the core, they are more effective and less costly. Our first ever strategy on voluntary return and reintegration will help returnees from both the EU and third countries to seize opportunities in their home country, contribute to the development of the community and build trust in our migration system to make it more effective.

There is plenty of room for critical analysis here. First, the precise number of 30 per cent is curious given that EU+ member states do not currently disaggregate return into ‘forced’ or ‘voluntary’ in their statistical reports, so it is hard to understand how Eurostat data could substantiate that figure. Second, significant political and financial investments over the last decade appear to have had little effect. Third, and relatedly, returnees may not want to seize those ‘opportunities’ if they are alienated from their ‘home country’. Finally, for countries of origin, return is less of an ‘opportunity’ and more of a loss. Remittances from citizens abroad often represent a major source of national revenue.

The new Strategy is short on details. There are brief references to the proposed EU Migration Pact, but they lack in detail and depth. There is much ado about return counselling, but this avoids macrostructural conditions in the origin state which factor heavily in migrants’ return decision-making. Transnational communication channels between a migrant ordered to return and service-providers in the country of origin with insights into post-return realities and expectation management, is barely alluded to in one, short sentence.

There are elements in the Strategy that arguably represent progress in the field. Perhaps most importantly, the strategy marks a shift in tone, from the law and order approach of the recast Returns Directive, launched in 2018 and still under negotiation, which in effect proposed restricting access to assisted return. So, too, there is open acknowledgement of the lack of an evidence base and the need for more research. Likewise, there is reference to the need for better monitoring of post-return service delivery and the need for common quality standards to ensure that returnees swiftly and effectively access the assistance they are promised in Europe pre-departure.

The new Strategy casts irregular migrants as people who can be motivated and convinced (‘counselled’) to choose to return, while depicting fragmented state policies as the problem. It calls for a more streamlined approach to address gaps between national return procedures, the absence of harmonized data, and variation in levels and types of support across member states, all of which are said to contribute to the low uptake in assisted return programmes.

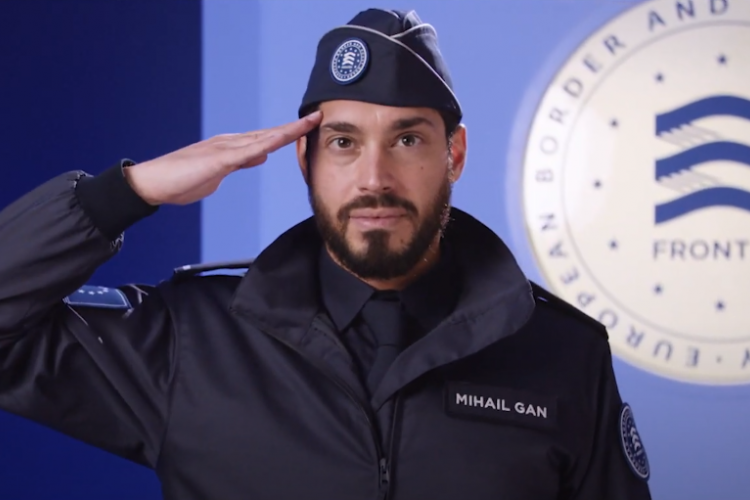

Surprisingly, given the emphasis on counseling and choice, the Strategy brings in the EU border agency Frontex as a key player in the field of assisted return, asserting that, ‘the role of Frontex as the operational arm of the common EU system of returns is key to improving the overall effectiveness of the system (…).’ Frontex is called upon to support an increasing number of voluntary return operations and reinforce its capacity to provide operational assistance to Member States in all phases of the voluntary return and reintegration process, including pre-return counselling (e.g. outreach campaigns to migrants), post-arrival support and monitoring the effectiveness of reintegration assistance.

Under the terms of the new Strategy, Frontex will take over some of the activities of the European Return and Reintegration Network (ERRIN), a hybrid network of national immigration authorities and NGOs that has been jointly contracting reintegration service-providers in origin states, overseeing the return of nearly 25,000 migrants, and offering a counterweight to the technocratic expertise of the hegemonic International Organization for Migration. Yet taking over some of ERRIN’s activities is just the tip of the iceberg. Supposedly, Frontex will

- Develop, jointly with the International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD), a common curriculum for return counsellors;

- Develop joint reintegration services;

- Ensure consistency in the content and quality of services;

- Develop a standing corps of return experts providing specialized support; and

- Bring together different strands of the EU return policy under the leadership of the Frontex Return Coordinator and a High-Level Network for Return, with national experts.

The Strategy contains no reflection on the obvious question that now arises. How can a law enforcement agency with expertise from border control and forced return truly be best positioned to take the lead on the EU’s delicate operation of assisted return?

The timing is more than a little off, of course, since the political ascendancy of Frontex has been dogged by serious controversies in recent months including alleged complicity in push-back operations whereby would-be asylum seekers were returned from EU borders. Frontex’ own response to these controversies, have raised uncomfortable questions about its willingness and capacity to hold itself accountable.

Poor timing aside, by appointing Frontex as the leader of assisted return the EU’s new strategy the European Commission adds a new layer of complexity to the task of presenting return programmes as benign, humanitarian interventions rather than as immigration control.

It seems more than likely that the rise of Frontex in the field of AVR will make ‘voluntary’ return more coercive and less regulated by rights. For instance, in the proposed EU Migration Pact, an expedited ‘border procedure’ denotes the pre-screening and detention of migrants near the Schengen border, and has been described by critics as ‘a second-rate asylum procedure’ with reduced procedural guarantees. The Strategy argues that an ‘effective’ border procedure will ‘facilitate and encourage voluntary returns since people will be available and more willing to cooperate with the authorities’. In this Orwellian twist, force and volition are truly one.

In short, the gently worded Strategy further blurs the line between assisted and forced return as soft and hard deportation. In doing so, it further necessitates criminological scrutiny and sensitivity to the language and actions of complicated punitive power, and on the diverse effects of this power on the EU, on host and origin states, and, not least, on ‘AVR beneficiaries’.

If there ever was a time for criminologists to turn their gaze towards assisted return, now is the time.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style)

Paasche, E. (2021). The Rise of Frontex in the EU’s New Strategy on Assisted Return. Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2021/05/rise-frontex-eus [date]

Share: