Places in Nowhere: Detention Centres, Police Departments and Pre-Removal Centres in Greece

Posted:

Time to read:

Post by Evgenia Iliadou. Evgenia is post-doctoral research fellow in Politics at the University of Surrey. She has conducted extensive ethnographic research in Greece and Lesvos on the refugee crisis, social suffering, border harms, temporal violence, vulnerability, and the lived experiences of border crossers. She has worked for many years as an NGO practitioner in refugee camps and detention centres, in Lesvos and the Greek mainland, and she has been member of various activist networks supporting people on the move.

In the aftermath of the 2015 “refugee crisis”, Greece attracted much attention due to the escalation of border violence and the infliction of harm against forcibly displaced people. Despite the new and increased attention on and documentation of border violence at sea and open refugee camps there is a relatively limited focus on the continuum of the implicit and routinised forms of violence against migrants inside police stations, pre-removal centres, and other detention facilities across Greece. Drawing on my first-hand, lived experiences as a female NGO practitioner, activist, and researcher for many years in border zones in Greece, in this self-reflexive blog I write about the violence continuum in sites of confinement. I argue that detention centres, police stations, and pre-removal centres are frequently inaccessible, isolated spaces and hidden from public view. In this respect most of them are places in nowhere. I will provide insights from the various sites of confinement I accessed in Greece as well as of the various forms of violence against refugees that I witnessed, but also experienced myself as a female practitioner in these sites across time. I argue that these places are harmful sites where violence is endemic and wherein even practitioners, like me who were supported by NGOs, can become vulnerable to state violence.

Out of sight, out of mind

Since 2005, I have worked as an NGO practitioner in refugee camps and detention centres by providing social support to forcibly displaced persons. I worked in many different sites of confinement in border zones in the Greek mainland and the islands. I was also actively involved for more many years in grassroots movements supporting refugees who were reaching Lesvos. These experiences were often shocking, traumatic and life changing as over time and through my different positionalities I witnessed the continuum of institutional and structural violence, the insult and violation of human dignity, the pain and suffering, and deaths of people seeking international protection in the hands of the Greek authorities, and more broadly by the proliferating thanatopolitical border regime. During my work as an NGO practitioner in Pagani I was overexposed to violence and intimidation. This violence and intimidation by the Greek authorities included: rape threats and sexual harassment, verbal and psychological violence through screams and shouting, symbolic violence through humiliation and devaluation, and everyday practices of intimidation beyond the institutional walls of the detention. I was frequently watched, stalked and harassed, accused of smuggling or espionage, and photographed by the police without my consent in public spaces of Lesvos.

In 2008 I traversed the threshold of Pagani closed detention centre on Lesvos island in order to provide social support to people who were fleeing persecution. The Pagani detention centre was located 4km outside the city of Mytilene (the capital of Lesvos), in an industrial zone. The detention centre was surrounded by abandoned allotments and in a sense was hidden away behind warehouses and wholesale businesses. If one was not aware about its existence and exact location, it would be very difficult to find. This is not surprising as most of these sites in Greece are inaccessible closed facilities, usually out of sight and out of mind.

This sense of remoteness is even more striking at the Greek-Turkish land borders in the Evros region. I have travelled several times to Evros and I had access to police departments, and closed detention centres such as Fylakio, Feres, and Tychero. In one of my first trips there I remember driving for hours in order to reach these facilities which were literally in the middle of nowhere. I remember the initial panic I felt when I realised how easily and silently one could become intercepted, push-backed and even forcibly disappeared, without leaving any traces. There were already several reports documenting enforced disappearances at the land Greek-Turkish borders but after 2015 these reports have significantly proliferated.

However, this sense of remoteness was and still is prevalent in detention facilities and police departments which can also be located within society’s social fabric. For instance, on Lesvos island there are multiple police departments, where border crossers are detained but these sites are frequently inaccessible to citizens, NGOs, activist networks, researchers, while even lawyers frequently have limited access. Similarly, in Athens the pre-removal detention centre in Petrou Ralli is also difficult to access - despite the proximity of the facility to the city centre - and is heavily monitored by the police. Likewise, the pre-removal detention centre in Amygdaleza is an infamous remote facility located in Attica.

Detention centres as sites of violence

Detention centres, police departments and pre-removal centres are sites of extreme violence. What was very striking when I was visiting police departments’ detention facilities in Athens was that many administrative detained refugees were held in appalling, inhuman and degrading conditions in basements. Some of them were detained for prolonged periods of time, sometimes more than 18 months, without having access to outdoor space, physical light and fresh air, to adequate hygienic and sanitary conditions, clean clothes and mattresses; they had limited access to information to asylum procedures, limited access to legal aid and social and psychological support. In such degrading conditions refugees were experiencing the violation of their human dignity. More broadly in the whole country there were and still are various police department detention facilities where the aforementioned conditions are replicated as a pattern. In Evros, I was shocked when during one of my visits in the facility in Feres I witnessed refugees being detained in a quite small warehouse-type facility within the police department and due to the overcrowded facilities, they were forced to sleep outside in the yard.

Similarly, in Lesvos - as in other sites - what was very striking was the routinisation of prolonged detention even of the unaccompanied minors who under the ‘protective custody’ of the state could spend months in structurally violent conditions, exposed to multiple forms of violence. Also, inside the hotspot of Moria there was a detention facility – known as Section B - wherein the deportable nationalities where detained. In Section B detainees had restricted access to international protection, limited legal aid and social care, and restricted access to information about the asylum procedures. What is even more striking is that for many NGOs, deportable refugees were not the ‘target group’ of their humanitarian intervention and, therefore, they were not of interest.

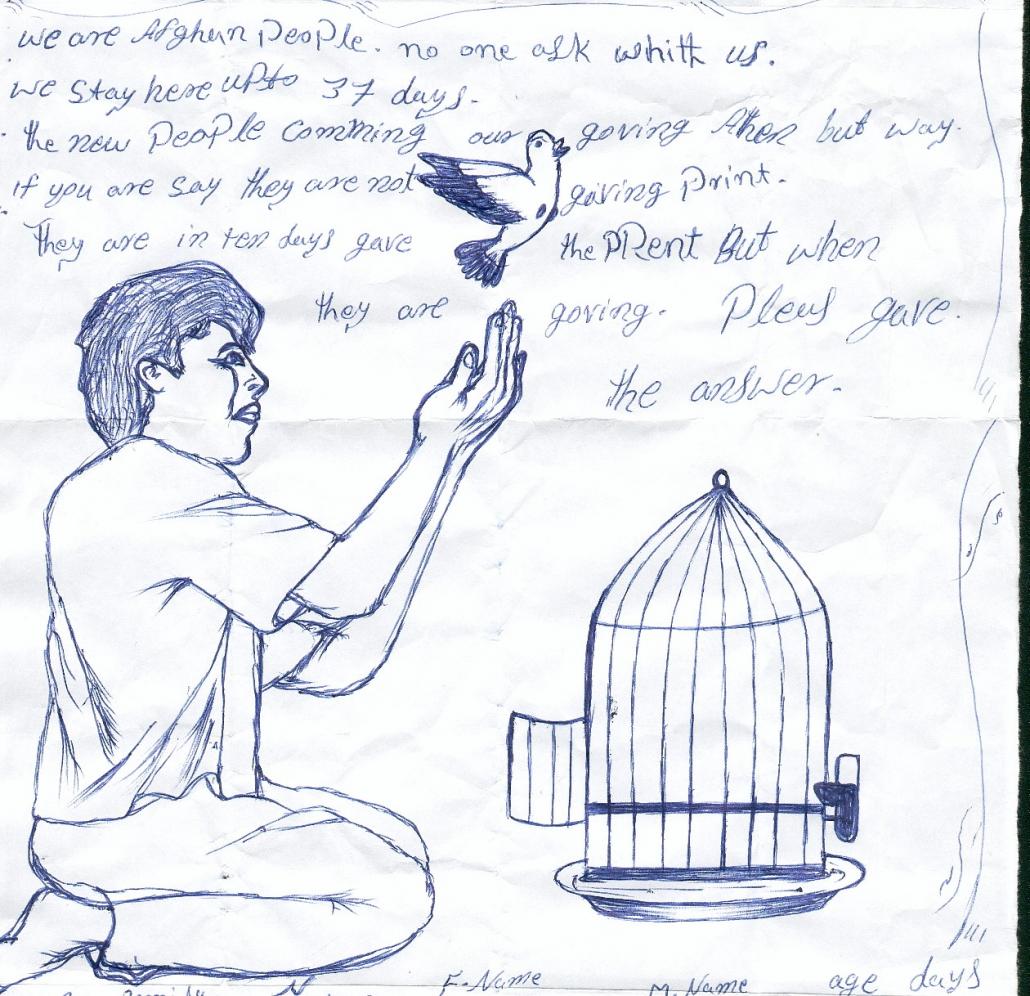

Finally, police department facilities, detention and pre-removal centres have for far too long been sites of infliction of temporal and therefore state violence, where refugees are detained for uncertain periods of time without knowing why and what they are (a)waiting for. Also, contra to other prisoners in jails, detained refugees in these facilities do not have the luxury of a sentence. As a result, their waiting becomes enduring, and their spatial confinement automatically also becomes a temporal one. As Médecins Sans Frontières note, ‘Residents have no idea when or how they will get out of here. Tomorrow they can receive a paper saying, ‘You will be deported’. Or they can be put in detention without any explanation without even a translator to explain to them what is going on.’ This uncertain and enduring waiting tantamount to a cruel punishment and torture ‘kills’ detainees quietly and slowly, mentally, emotionally, and even physically. I have witnessed myself many detainees harming themselves by hitting their heads against the iron bars and the walls until they bleed, or by cutting themselves due to anxiety and despair.

In this self-reflexive post, I have argued that police facilities, closed detention centres and pre-removal centres in Greece wherein forcibly displaced people are routinely detained for uncertain periods are remote and inaccessible places wherein violence is endemic. Yet, these sites are under-researched despite the attention that Greece has attracted after the 2015 refugee crisis. As a result, these places in nowhere routinely and continuously operate as blackholes and the need for more thorough and holistic research is urgent.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style)

Iliadou, Ε. (2021). Places in Nowhere: Detention Centres, Police Departments and Pre-Removal Centres in Greece. Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2021/05/places-nowhere [date]

Share: