The Uneasy Coexistence of Transfers and Deportations in Schengenland

Posted:

Time to read:

Guest post by José A. Brandariz, University of A Coruna, Spain. José is an associate professor in criminal law and criminology at the University of A Coruna, Spain, and associate editor of the European Journal of Criminology. This is the second post of Border Criminologies themed series on 'Transfers of Foreign National Prisoners/Probationers'.

Since the late 2000s, the EU has constructed a sophisticated legal architecture plan to transfer indicted and sentenced EU nationals from the European jurisdiction in which they are prosecuted and sentenced to their home country (see e.g. Framework Decisions 2008/909/JHA, 2008/947/JHA, and 2009/829/JHA). These legal instruments aim to share the criminal justice burden among EU member states and potentially benefit Western European criminal justice systems dealing with sizeable Eastern European national clienteles. From a (Western) state perspective, there are good reasons to embrace this cost-effective agenda. In January 2018, 30,857 EU citizens were imprisoned in Western EU countries, accounting for 29.8% of their foreign prison populations (source: SPACE I). In addition, in 2017 noncitizens accounted for over one quarter of the arrested and cautioned individuals in a number of EU jurisdictions such as Austria, Belgium, Germany, Greece, Italy, and Spain (source: Eurostat).

In sharp contrast to this, these criminal law cooperation policies have been hardly used in practice. As confirmed by SPACE I data, transfer procedures have had an insignificant impact on the European penal landscape, with very few exceptions, such as Romania. A variety of factors may explain this apparent failure (see work by Stefano Montaldo and others). This post examines a specific aspect, that is, the overlapping of transfer measures with the deportation of EU citizens.

The deportation of EU nationals was not envisaged as a crucial component of the EU system of coercive management of human mobility. According to the Directive 2004/38/EC, the deportation of EU foreign nationals cannot be based on regular migration law breaches (e.g. irregular border crossing, undocumented stay), but only on serious motives of public policy, public security, and public health.

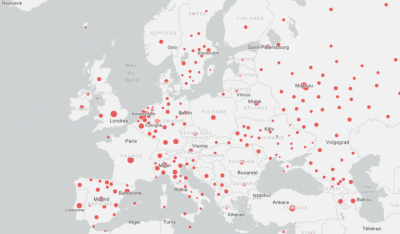

Despite this stringent legal framework, empirical data illustrate that the deportation of EU nationals is far from being a marginal phenomenon. From 2015 to 2019, on average 4,190 EU nationals were forcefully deported per year from Britain (source: UK Home Office), and 3,040 EU nationals were deported from France annually (source: French Home Office). National databases reveal that significant contingents of EU nationals are also deported from other EEA jurisdictions, such as Germany, Greece, Norway, and Spain. In short, deportation policies targeting EU national populations are being consolidated across Europe, in close connection with crime prevention strategies. In fact, combatting crime has been the main driver of these policies. In some cases, however, such deportation arrangements are adopting pre-criminal adjudication schemes, since they target destitute and allegedly troublemaking populations engaged in extreme poverty-related behaviours.

Given this focus on crime and pre-crime concerns, there is a certain overlapping between transfer procedures and deportation practices, as they seem to be designed to tackle criminal activities carried out by EU nationals. Despite this overlapping, transfers and deportations are in principle distinct legal institutions. Transfer procedures compel inmates and defendants to serve their sentences in their home countries, but do not entail the imposition of a subsequent ban on entry to the country instigating the transfer. By contrast, deportation orders lead to the enforcement of entry bans, but they do not entitle the criminal justice agencies of the destination country to hold EU citizens criminally accountable. In addition, crime-related deportation orders stand at odds with criminal law goals, namely social rehabilitation but also incapacitation.

Such divergences between transfer procedures and deportations might suggest that both legal tools can coexist and that transfer protocols should prevail over deportation practices targeting EU citizens. However, in the context of overburdened criminal justice systems that are forced to come to terms with the principle of scarcity, the uncontroversial coexistence of deportation and transfer measures is in practice less feasible than legal regulations apparently imply.

From a rule of law viewpoint transfer procedures might seem preferable, but deportations rank first once pragmatic managerial tenets are considered, as they save much-needed criminal justice resources, reduce the workload of law enforcement agencies, and ultimately realise the political goal of getting rid of the unwanted alien as expeditiously as possible. Therefore, efficiency-oriented mentalities are enabling the prevalence of deportation orders over transfer procedures, at least in countries featuring widely developed deportation systems.

In scrutinising the transfer-deportation overlap, an additional aspect should be taken into account. Many EU jurisdictions have succeeded in articulating wide-ranging arrangements to deport unwanted EU citizens. This is not at all easy, for it requires assembling political will, resources, and complex logistical and organisational measures. By contrast, EU countries have failed in organising a similar institutional structure to expand the utilisation of transfer measures. This divergence should be explored from the perspective of institutional interests. In carrying out deportation practices, national administrations, especially police agencies, deal with procedures that are almost completely under their control, with few – if any – judicial interventions. Deportations are largely automated procedures that, unlike transfers, are not dependent on decisions made by judicial authorities on a case by case basis. This obviously facilitates the unobstructed development of the migration control agendas of national governments. What is more, the deportation of EU nationals is one of the cases in which EU member states may make their national interests prevail in the framework of a multi-scalar migration management system.

Judicial actors and bodies, in turn, do not seem to have the political determination and political capital needed to set up a wide-ranging institutional apparatus to enforce transfer procedures. In addition, judicial officials, being traditionally self-conceived as nation state-centred actors, have a hard time operating within international arenas in which – as in the case of transfers – no apparent national interests seem to be at play. At least in this respect, the highly praised judicial nature of transfer procedures has run counter to the institutional goal of consolidating a continent-wide system for transferring – instead of deporting – incarcerated EU nationals.

Disclaimer: This post has been drafted in the framework of the research project Trust and Action (GA 800829), funded by the European Union Justice Programme 2014-2020 - www.eurehabilitation.unito.it. The content of this post represents the views of the members of the research consortium only and is their sole responsibility. The European Commission does not accept any responsibility for use that may be made of the information it contains.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style)

Brandariz, J. A. (2021). The Uneasy Coexistence of Transfers and Deportations in Schengenland. Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2021/01/uneasy [date]

Share: