Guest post by Asher Websdale. Asher is a Junior Researcher. His current research focuses on the violation of human rights occurring through internal-border police checks in the Schengen Area. Asher can be found on Twitter. This post is part of our themed series on border control and Covid-19.

Last month I wrote a post discussing the “parallels witnessed between the behaviour of states and their borders in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic and those uncovered by crimmigration”. One month on, I felt it was necessary to reflect on the latest developments in the USA.

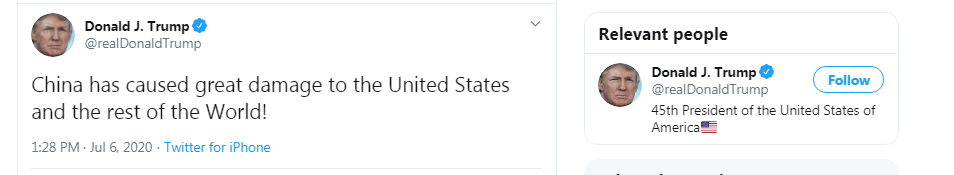

A post recently written by Simone Durham and Dr. Rashawn Ray in the Border Criminologies themed series on Crimmigrant Nations detailed their analysis of tweets by President Trump concerning crimmigration discourses in the COVID-19 era. They referred to the shift from his initial positive tweets to a more negative tone and frequent use of the term “Chinese virus”. Taking inspiration from their work, in this post I begin by examining Trump’s more recent tweets. Trump has since veered away from the use of the term ‘Chinese virus’ in favour of a similarly offensive “China virus”. At the time of writing (11/07/2020) Trump’s tweets/re-tweets have made reference to the “China virus” eight times in the last six days. In fact, Trump has reignited his Twitter tirade of blame against China as the source of COVID-19.

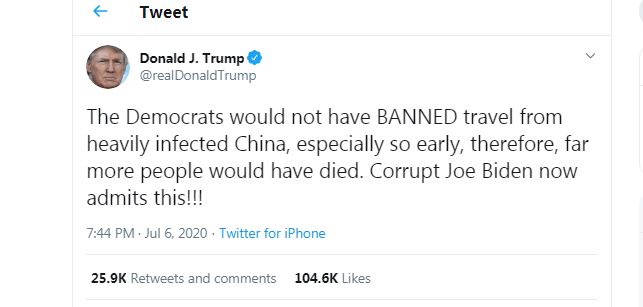

Later that same day, he used these blame politics as a tactic to hail his own success as a pandemic leader.

Trump’s relentless portrayal of China and Chinese people as the passage through which COVID-19 was introduced to the US has worked to merge Chinese identity with the picture of an external public health threat to the US. This not only works to camouflage his own catalytic apathy towards the virus but also ignores the potential role that Europeans played in bringing the virus across the Atlantic. On 13th March Trump issued a travel ban on 26 European countries and their residents from entering the US - so why has Trump not tweeted about Europe or Europeans since 20th May? One could draw comparison between this example of arbitrariness and the apparent geo-political reasoning behind the omission of Saudi Arabia from the “Muslim-majority” travel bans.

Nevertheless, what we witness is undoubtedly a disproportionate attack on Chinese people as COVID-19 vectors. As I wrote last month: “naming a disease after a specific identity marker, such as nationality, religion or political affiliation, these identities are coupled directly with the cause of disruption - the disease. This works only to blame and subsequently exclude these people”. As incidents of racism toward the Asian community continue to occur in the US, Trump’s use of public health threats work in the same manner as his utilisation of crime to fuel anti-migrant discourses. To refer back to Durham and Ray’s work, Trump has certainly “extended his crimmigration and racialized anti-immigrant rhetoric to the COVID-19 pandemic”.

Trump has also continued to use the public health crisis to accentuate the necessity for the completion of his ‘beloved’ wall at the Southern border. Again, turning to Twitter, I would like to draw attention to the similarity in terminology between these two following tweets.

Much like his merging of migration policy and public health securitisation, Trump’s hyperbolic concern for the spread of the virus at the border is tainted by his “America First” Weltanschauung. Within Trump’s protective border paradigm exists a dichotomy concerning halting the spread of COVID-19. On the one hand, Trump has referred to returning “crossers” at the border and preventing a coronavirus catastrophe within the USA. On the other, The Marshall Project and the New York Times exposed how the Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency (ICE) have been exporting COVID positive detainees from cramped and unsanitary detention centres - the type of conditions within which a pathogen can thrive - on deportation flights around the world. At the time of writing 11 countries have confirmed that deportees returned home from the US with COVID-19. ICE was instrumental in the US’ removal of individuals with criminal records and contemporarily appear to be one of Trump’s “public health authorities” keeping the nation safe from the “invisible enemy”.

In my previous post, I wrote how we must avoid the merging of anti-migrant sentiments and public health securitisation at the border. What this post seeks to do is highlight the USA as an example of how populist narratives have triumphed in achieving this apparent merge. The starkest parallel between the merging of migration and public health and crimmigration lies in the aim of such merges: security. Of course, the USA is not the only example. Around the globe similarities between public health securitisation policy and crimmigration are abundant: the scapegoatism of Ethiopian migrants in Yemen, the added obstacles faced by refugees whilst planes continue to fly for the privileged, racial biases exhibited through lockdown measures and the portrayal in some areas that Black Lives Matter protests may contribute to an upsurge in cases. What is evident is that states rarely miss an opportunity to consign the safety of others beneath the perceptions of their own security.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style)

Websdale, A. (2020). One Month On: Trump and Public Health Securitisation at the Border. Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2020/07/one-month-trump [date]

Share: