Guest post by Austin Kocher. Austin Kocher is a Faculty Fellow at the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse(TRAC), a research institute at Syracuse University. TRAC uses Freedom of Information act Requests (FOIA) to provide insight and transparency about several areas of US federal law and law enforcement. TRAC also serves as a clearinghouse for data on immigration enforcement. Austin’s research focuses on the critical legal geographies of immigration policing, the immigration courts, and immigrant rights movements in the United States.

Although President Trump often claims that immigration enforcement efforts focus on immigrants with criminal convictions, in-depth data on immigrant detention from Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) shows the opposite to be true. The number of immigrants in the United States held in civil immigrant detention centers has grown in the past few years, but as I show below using data obtained by TRAC in our study of the US immigration enforcement system, this growth is due entirely to immigrants with no criminal conviction or low-level criminal convictions. Not only does this finding challenge ICE’s narrative, but it illuminates the value of using Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests to hold states accountable and to ensure government transparency.

Government Data is about Narrative, not Just About Numbers

When governments control their own data, they control the story. Michel Foucault describes the way that knowledge of the “things that comprise the reality of the state” became known as statistics. Statistics, or counting up elements of the social world which the state seeks to govern—includes population, natural resources, and manufacturing output which allows the state to calculate risk, implement economic and social control policies, and construct institutions. Foucault had in mind the way that knowledge about the state is itself a form of power and how the creation of state knowledges and their selective deployment enables the state to govern. In particular, the selective publication of statistics allows state agencies to narrate their own stories in allegedly neutral ways to influence public perception. This is certainly applicable in the world of immigration enforcement, where ICE touts arrest, detention, and deportation statistics and through official accounts on Instagram and Twitter in order to present an image of ICE’s work as dangerous yet effective.

ICE’s statistical story-telling representation of its work does not go unchallenged. Using Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests and litigation in the courts, researchers have successfully gained access to the underlying data and databases used by ICE to generate statistics for the public. Accessing, analyzing, and publishing this data is a way of telling different stories, unsanctioned stories, about how the state works, and a way in which we question misleading or inaccurate data provided by the state.

Our research at TRAC relies on frequent FOIA requests to provide insight about how the federal government functions, especially when it comes to immigration enforcement. By using government statistics rather than raising questions about the underlying production of statistical forms of knowledge, we risk reproducing state forms of knowledge. Yet access to and dissemination of the state’s own data also allows us raise important questions about the state’s justification and representation of its immigration enforcement projects. TRACs work is a way of shifting the narrative about immigration from one written solely within the halls of power to a public narrative that is open to scrutiny, transparency, and democratic debate.

Immigrant Criminality: Fact and Fiction

Few research topics have been as central to immigration studies as the increasing securitization of immigration controls through the perception of immigrants as terrorists, criminals, or other threats to the developed world. As César García Hernández argues in his recent book, Migrating to Prison, politicians have long relied on the “stigma of criminality” (113) to justify every-growing immigration policing, detention, and deportation programs. César’s work expands on the work of Leo Chaves’s The Latino Threat, which examined the cycle of paranoia produced by politicians and the media about immigrants as dangerous criminals thereby justifying aggressive policing, detention, and border controls.

The distance between myth and reality about immigrant criminality, however, is vast. Our recent findings show that ICE’s story about focusing on threatening and dangerous criminal immigrants deviates from the reality of their own data. Specifically, we recently looked at case-by-case detention data that provided “snapshots” of who was sitting in immigrant detention centers across the U.S. on a single day.

We found two significant trends in immigrant detention data that challenge ICE’s narrative focused on perception of immigrants as criminals. These findings illuminate the ongoing need for researchers to question not only the discursive representation of immigrants as criminals, but to also question ICE’s representation of itself through statistics they produce.

Finding 1: The Growth in U.S. Immigrant Detention is Driven by Non-Criminal Detainees

According to data we obtained, there is a steady growth in the total numbers of immigrants held in detention in each of the months for which we have data. On the last day of April 2019, nearly 50,000 immigrants were in detention in the United States, the highest number in this data set. This is nearly double the number of detainees in March 2015, when just over 25,000 immigrants were held in detention.

Even more significantly, however, this growth was driven entirely by detainees with no criminal convictions. In April 2019, 64% of detainees had no criminal conviction compared to just 40% four years prior. In fact, without non-criminal detainees, detention numbers would have actually declined slightly between early 2018 and early 2019. The number of detainees with criminal convictions remained relatively constant across time, hovering between 15,000 and 18,000 detainees.

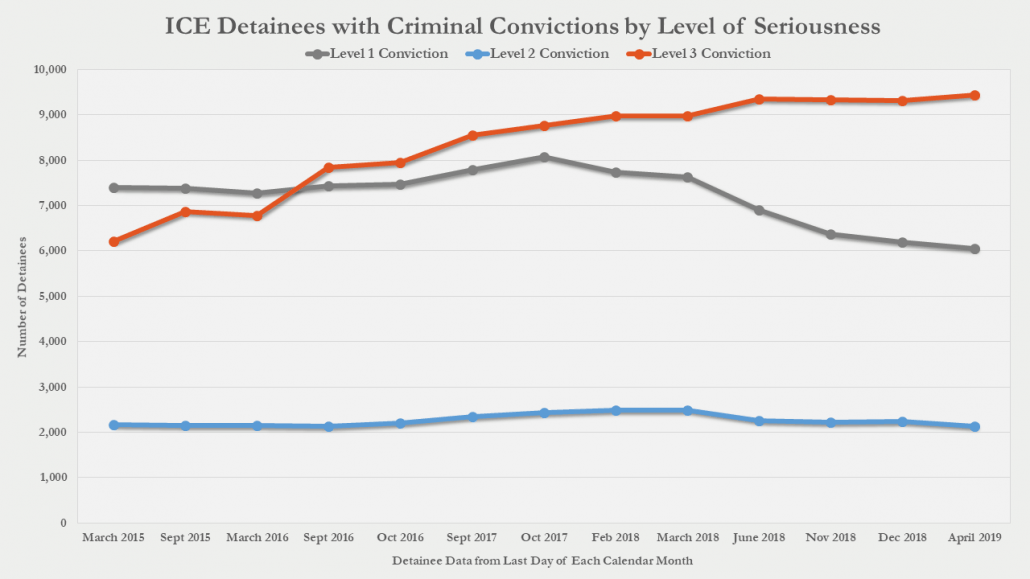

Finding 2: Fewer Immigrant Detainees in U.S. Have Serious Criminal Convictions

Although the number of detainees remained relatively constant over this time period, these numbers obscure the fact that a significant compositional change occurred that reflected a decrease in the number of allegedly “serious” criminal offenders held in detention over time. The total number of detainees with Level 1 convictions, such as assault or burglary, actually declined steadily between October 2017 and April 2019, while the number of detainees with Level 3 convictions, such as a routine traffic offense or other misdemeanor, grew to compensate for this decline.

The number of detained immigrants convicted of serious felonies fell from between 7,500 and 8,000 in 2017 to just above 6,000 in April 2019. Detainees with Level 3 convictions climbed steadily from just over 6,000 (or 39 percent of the total detainees with criminal convictions in 2015) to nearly 9,500 (or 54 percent) in 2019. The number of detainees with Level 2 convictions, such as larceny or illegal re-entry, remained unchanged across these four years, hovering somewhat above 2,000 detainees, or between 12 and 14 percent of all detainees with criminal convictions, on any given day.

Problems with Using Criminal Convictions in Civil Detention

Although the success of anti-immigrant rhetoric attempts to make the connection between undocumented immigrants and criminality appear “natural”, there is nothing natural about holding immigrants with or without convictions in for-profit civil detention centers. There are four important caveats to this data.

First, the U.S. Supreme Court has found that immigrant detention is a civil form of custody which is distinct from incarceration in that it is not intended to be used as a criminal punishment. This means that the detainees included in this report are not in detention because they are serving out a sentence related to their conviction. Rather, when non-citizens are sentenced as part of a criminal conviction, they serve out criminal sentences within the federal, state, and local prisons. In contrast, ICE oversees much of the civil immigrant detention system.

Second, for many of the detainees described here as "criminals", the criminal convictions on record represent crimes that do not neatly conform to popular stereotypes about criminality, including non-violent crimes, simple traffic citations, or immigration violations.

Third, many detainees listed as "criminals" received a conviction years or even decades in the past and served out their sentences, probations, and satisfied other conditions associated with their convictions.

Fourth, although I rely on the criminal/non-criminal distinction for this report, a distinction which is common within ICE's own reporting, I am in no way promoting a value distinction between immigrants with criminal convictions and immigrants without criminal convictions. Using ICE definitions, in fact, most U.S. citizens have engaged in some form of "criminal activity" such as speeding, jay- walking, and other minor infractions of the law.

From Challenging State Narratives to Challenging State Practices

Showing that most of ICE’s detainees have no conviction or a low-level conviction on their records is an important step in challenging the “stigma of criminality” that fuels immigration detention. But challenging narratives is not enough. Narratives are rooted in the institutional spaces and practices of immigrant detentions centers and extend out into the criminal justice system, which is itself complicit in producing a racialized “caste system” that disproportionately affects African Americans, Native Americans, and Latino/a immigrants. Efforts to merely reform immigrant detention, as César García Hernández argues, may only “entrench them further rather than threaten their existence” (143). Nonetheless, exposing the manifestly contradictory accounts between state narratives about “criminal” immigrants and the reality of the government’s own data is an important step towards dismantling the state’s monopoly on statistical forms of knowledge and governance.

To see all of TRAC’s immigration data tools, visit https://trac.syr.edu/phptools/reports/reports.php.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style)

Kocher, A (2020). Challenging State Narratives about Immigrant Criminality. Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2020/05/challenging-state [date]

Share: