A NGO’s dilemma: rescuing migrants at sea or keeping them in their place?

Posted:

Time to read:

Blog post by Julia Van Dessel and Antoine Pécoud. Julia is a PhD researcher at Université Libre de Bruxelles and Antoine is a Professor at University of Sorbonne Paris Nord.

In 2019, the Spanish NGO Proactiva Open Arms launched an information campaign in Senegal, with the objective of dissuading would-be migrants from irregularly migrating to Europe.

Created in 2015, Proactiva Open Arms is one of the leading NGOs in “Search And Rescue” (SAR) activities in the euro-Mediterranean region, along with others like SOS Méditerranée, Jugend Rettet or Sea Watch. Faced with daily shipwrecks and the thousands of migrant deaths occurring off the Greek and Italian coasts, these NGOs renewed well-established principles of solidarity at sea and chartered boats to rescue migrants.

While there is much support for this innovative pattern of civil society activism, SAR NGOs also face the hostility of EU governments. The border is a key site of national sovereignty and their presence in European maritime border-zones irritates states. For instance, some states have argued that, by saving migrants’ lives, NGOs facilitate unauthorized migration and become smugglers’ and traffickers’ partners in crime.

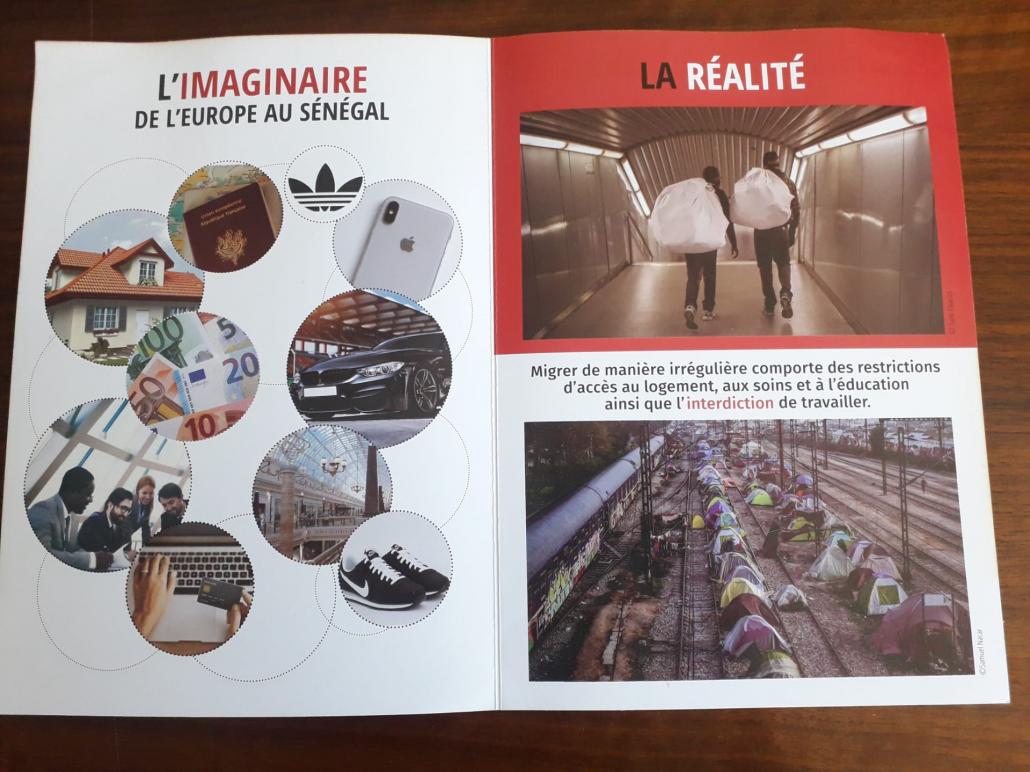

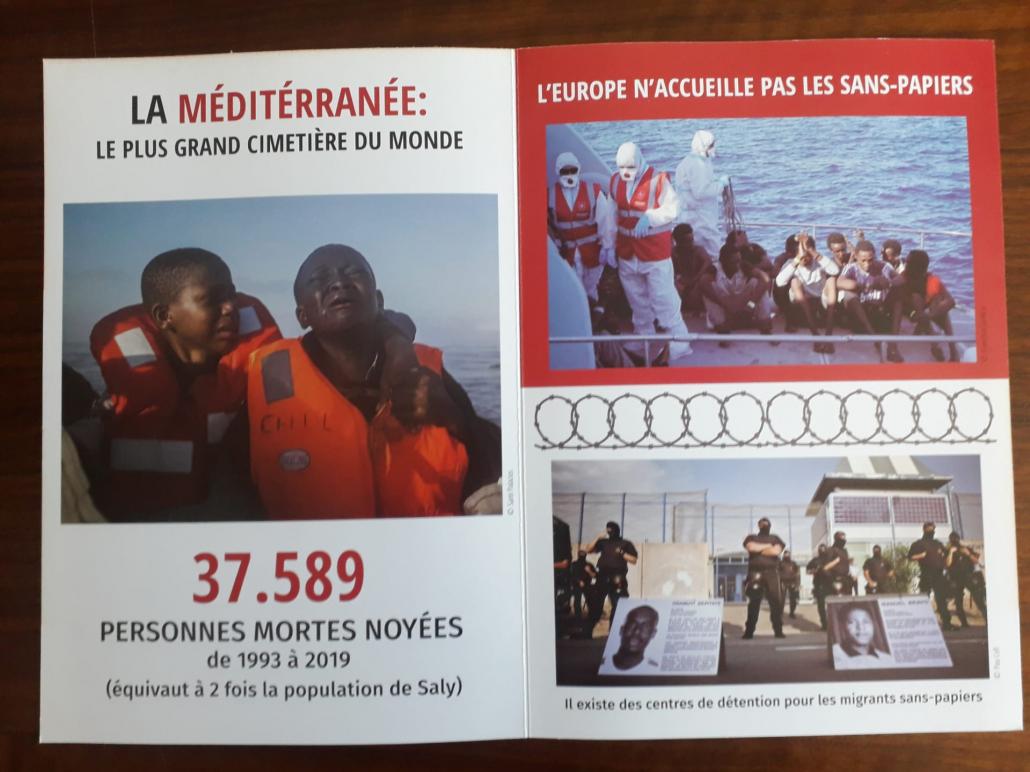

Today, Proactiva Open Arms is extending both the geographical scope and the strategic orientation of its operations. By working in the Mediterranean Sea, this NGO has realized that ‘once in the sea, there is no solution’. Therefore, and even though ‘migration is a fundamental right’, they have decided to start an information campaign in West Africa because ‘the solution is not here. It is at the origin’. Introduced in Senegal last year, the objective of the “Origin” project is twofold: to promote economic alternatives for the youth and to set up a network of local volunteers trained to “deconstruct the imaginary about migration to Europe”.

This is not a new idea. By running information campaigns to discourage migration, Proactiva Open Arms merely imitates what states and international organizations have been doing for decades. For example, in 2007, the Spanish government funded a video spot to raise awareness in Senegal about the dangers of irregular migration, featuring the famous Senegalese musician Youssou N’Dour. This was done in cooperation with the International Organization for Migration (IOM), an organization that has long specialized in organizing similar campaigns throughout the world. More recently, in 2015, the launch of the EU Emergency Trust Fund addressing the “root causes of irregular migration in Africa” paved the way for large scale initiatives on the continent such as the “Tekki Fii” (“Make it here” in Wolof) multimedia campaign, which highlighted “success stories” of local entrepreneurs in Senegal and the Gambia.

Proactiva Open Arms’ project rationale thus reiterates the arguments that are traditionally put forward to justify information campaigns. First, people in sending regions are unaware of the hardship of migration realities and candidly see Europe as a ‘promised land’. Second, their ignorance makes them vulnerable, because cruel smugglers and traffickers will exploit their naivety to embark them on dangerous journeys. Third, young and dynamic people should not migrate because their country of origin needs them to develop. This is why, in an often paternalistic and somewhat neocolonial fashion, Europe strives to convince ignorant Africans that their best option is to stay at home. This is also why these campaigns cynically use images of the harsh treatment facing migrants (deaths, camps, poverty) as reasons not to migrate.

Whereas Proactiva Open Arms challenges European politics in the Mediterranean, it aligns itself on Europe’s objectives in Africa. By saving migrants’ lives at sea, it contests the main concerns of European states, which prioritize border controls regardless of how many deaths occur in the process. However, by setting up campaigns to dissuade would-be migrants to leave Senegal, it does exactly what the same European states have been doing for years, contributing to their overall objective of keeping people in their place.

How can we make sense of this odd situation? A first answer lies in the well-known pitfalls of humanitarian activities. SAR NGOs are above all concerned with saving lives. This is an unquestionably urgent and sensible objective—which is also in line with the proclaimed neutrality that has long characterized humanitarian work: the purpose is ‘just’ to save lives, not to intervene in politics. This is why SAR NGOs blame European states for inhibiting their work, for example by blocking their boats or their access to ports, but without going much further in the denunciation of the overall context in which these deaths occur.

This leaves open the broader issue of the restrictive migration regime, which dominates European politics but fails to properly address the consequences of the socio-economic and political imbalances that characterize the relationships between Africa and Europe. Thus, in the eyes of Proactiva Open Arms, keeping potential migrants in Africa seems like a simple and efficient solution to save lives. Yet, in the face of development differentials, demographic trends, and the need for cheap and undeclared foreign workforce in Europe, this straightforward solution is unlikely to work.

A second answer may have to do with the often implicit postcolonial roots of European migration politics. One of the key features of colonial power was the lack of distinction between ruling and civilizing: dominated populations were to be controlled in their own interests, which legitimized the use of violence and coercion. At the EU's external borders, this mixture of care and control now takes the form of a "humanitarian-security" nexus, which portrays the irregular migrant as a victim and frames border control as a life-saving activity, in the interests of migrants. In this vein, information campaigns assume that migration must be controlled, not only in the interests of receiving states, but also to protect migrants themselves from abuses such as trafficking. To a large extent, this belief is shared by states and NGOs alike, which is why both organize information campaigns; this illustrates a seemingly counterintuitive convergence between states’ control apparatuses and NGOs’ humanitarian concerns.

There are NGOs that are exceptions, however. For example, Alarm Phone Sahara is a Niger-based network of associations that promote the free movement of people while also providing migrants with information and advice when crossing the desert. As Charles Heller writes, this type of initiative is very different from mainstream migration information campaigns: “While the flyer does inform migrants on these dangers, it takes the starting point that many people will leave despite knowing them and, as such, it provides migrants with information as to key security measures and their rights.” Yet, overall, ‘informing’ migrants today predominantly means discouraging them from leaving, and whether the message comes from state or non-state actors makes little difference.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style)

Van Dessel, J and Pécoud, A (2020). A NGO’s dilemma: rescuing migrants at sea or keeping them in their place?. Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2020/04/ngos-dilemma [date]

Share: