Guest post by Gregory L. Cuéllar. Gregory is Associate Professor of Old Testament at Austin Presbyterian Theological Seminary. His areas of research are religion and migration studies and museum studies and archive theory. He is currently completing two books, Resacralizing the Other at the US-Mexico Border for Routledge (2020) and Religion in Immigrant Detention: Resisting Faiths in a State of Removal for Palgrave (forthcoming). His most recent book is titled, Empire, the British Museum, and the Making of the Biblical Scholar in the Nineteenth Century Archival Criticism (Palgrave, 2019).

As early as 1911, the US federal government had installed a kosher kitchen in its detention facility at Ellis Island to accommodate immigrant Orthodox Jews. During the same period in the UK, a parliamentary committee was commissioned to establish a ‘receiving house for alien immigrants’ at what Daniel Wilsher calls ‘London’s Ellis Island.’ Included in the committee’s plans for this detention facility was the provision of a kosher kitchen for Jewish immigrants.

Today in the US and in the UK, accommodating the religions that migrants bring with them into detention falls mainly on the private prison companies (UK IRCs: Mitie, GEO, G4S, Serco; and US Detentions: GEO Group, CoreCivic) contracted to manage these facilities. Although each of these companies has distinct approaches to immigrant detention, their provisions of religious care are guided by specific government standards. In the UK, these are The Detention Centre Rules 2001, and in the US they are stipulated in Performance-Based National Detention Standards 2011 (PBNDS 2011). In accordance with US and UK detention standards, the private prison companies are required to hire religious care personnel (UK: ‘Managers of Religious Affairs and Ministers of Religion’; US: ‘Chaplain or Religious Services Coordinator’) and provide relevant programing and sacred spaces for religious worship and learning.

2018 photo of Buddhist prayer room at Harmondsworth (Heathrow IRC), Immigration Detention Archive, Border Criminologies, University of Oxford, management contract with Mitie

2019 screen shot photo of a multi-purpose chapel at Otay Mesa Detention Center in San Diego, California, Intergovernmental Service Agreement with CoreCivic

In the US, the First Amendment protects the constitutional rights of immigrants to practice their religion of choice when in detention, while in the UK the right to freedom of religion in detention is protected under Article 9 of the European Convention on Human Rights. In my UK fieldwork this past summer (2019), I visited Brook House (Gatwick IRC), Harmondsworth, and Colnbrook (Heathrow IRCs). The former is managed by G4S and contains a Christian chapel (with a capacity for sixty people) and a separate multi-faith room. At Heathrow Mitie operates a number of rooms (“World Faith Rooms”) for different religious traditions: Evangelical Christianity, Eastern Orthodox, Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism, and Sikhism.

The Managers of Religious Affairs at the Gatwick and Heathrow IRCs are ordained clergy in the Protestant/Evangelical Christian tradition, while their Ministers of Religion (chaplains) reflect the faith traditions most represented among the detainees. In the US system, the Manager of Religious Affairs is the Detention Chaplain. Immigration detention centers there possess no interfaith teams of chaplains nor distinct worship spaces for non-Christian detainees. In my research, I have yet to encounter a non-Christian Manager of Religious Affairs (UK) or Detention Chaplain (US). In both contexts, it seems, the Christian tradition remains the default religion in programing, literature, sacred spaces, and religious personnel, even when, for instance, at Brook House and Tinsley House the majority religion among detainees is Islam.

A range of evidence suggests that detainees find some relief from religious care in detention. Yet press reports in both countries have also revealed egregious and shameful violations of migrants’ religious freedoms in immigration detention. The multiple stakeholders investing in immigration detention in the US and UK, from the state level to the private sector, represent the gatekeepers to how religious care should function within immigration detention. As revealed in the press reports above, this power dynamic allows for religion to be used either as a source of healing or trauma for immigrant detainees.

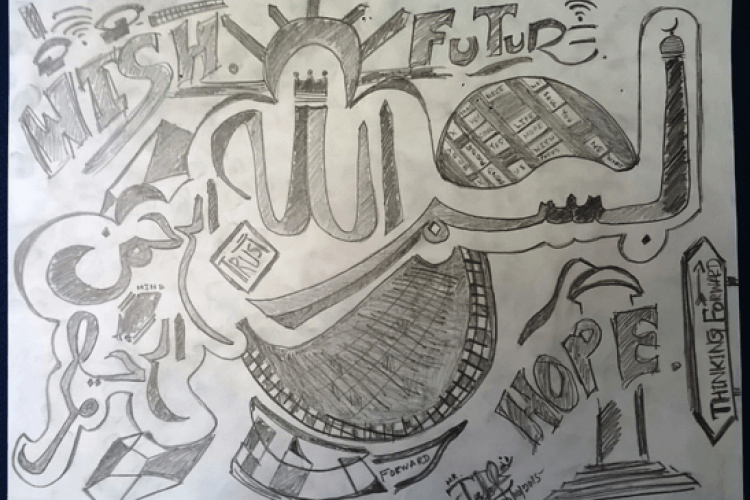

Bismillah ir Rahman ir Raheem (In the Name of God the Most Gracious, Most Merciful), 2015, Pencil drawing, 9 ´ 12² (22.9 ´ 30.5 cm), Immigration Detention Archive, Border Criminologies, The University of Oxford (produced in detention)

Expressions, symbols, and images of religious belief can be found in contemporary artistic productions of detained migrants. Take for instance the drawing above, titled Bismillah ir Rahman ir Raheem (In the Name of God the Most Gracious, Most Merciful). It is part of a larger collection of artwork called the Immigration Detention Archive, at the Centre for Criminology at the University of Oxford. The collection includes artwork created by immigrant detainees in the art rooms of two different Immigration Removal Centres (IRCs): Campsfield House, outside Oxford; and Colnbrook, adjacent to Heathrow Terminal 5. The vast majority of those detained in the multiple IRCs scattered across the UK are men, and most are from former British colonies or sites of recent conflict. The top five nationalities of those leaving detention in March 2016 were: Pakistani, Indian, Albanian, Bangladeshi, and Nigerian (see work by Mary Bosworth). In this carceral context, the fear-deportation syndrome is an everyday reality for these immigrant detainees. After consulting the entire collection, I identified several drawings with religious themes like the one above.

Mirna, Dios estuvo siempre con nosotros (God was always with us), marker, 2016, 11 ´ 14² (28 ´ 35.5 cm), Arte de Lágrimas Refugee Art Gallery

This drawing, titled Dios estuvo siempre con nosotros (God was always with us), was created by an adult mother from El Salvador. After her release from a Family Immigrant Detention Center in Dilley, Texas, US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) had taken her and her son to the Central Bus Station in San Antonio, Texas. I met Mirna when she arrived at the bus station, where I was working with a team of graduate students to provide food and hospitality to asylum-seeking families. These families were usually released wearing GPS ankle monitors. While sitting with them in the bus station, we offered them art materials to pass the time while they waited for their buses. In the drawing, Mirna tells the story of her migratory journey to the US. On the left side she writes, ‘I only know God was always with us and will be there for everything we lack for accompanying from point we started this trip, I praise and bless him forever. Despite the suffering he gave us strength to embolden our faith.’

Within the academic professional literature very little has been written on the role of religion in immigration detention. In my work, I seek to understand how people’s faith can offer a source of support in detention. I am also interested in how and whether religions shift behind bars. To what extent does religion inform detainees’ vision of liberation in immigration detention? I am also interested in institutional factors. How have private prison companies implemented standards for religious care in these institutions? Are there particular religions that private prison companies tend to privilege in immigration detention? What specific type of training or education do private sector religious personnel receive to care for migrant trauma?

Βoth governments have distinct standards that define and regulate religious care and practice in their immigration detention complexes. The rules stipulated in these standards point us to a series of state actors who exert high levels of control and influence over the provision of religious care in immigrant detention. When read critically, they reflect strategic investments on the part of the state to ensure a particular kind of religious experience in immigration detention, whereby religion assembles into state approved spaces, personnel, programming, literature, food, and dress. By entrusting private prison companies with the implementation of the state’s standards for religion in immigration detention, it expands beyond a human right to now a profit-seeking privatized service.

When considering the carceral logic that undergirds immigration detention and the state actors and private managers determining the nature of religious care within it, religion comes forth not solely as a positive force but rather as a lucrative domain to shape the beliefs of detainees and hence influence their social decisions (See my article). In this article, the policy in question pertains to state approved religious care in U.S. family detention centers (mainly single mother-child families). In my analysis, I incorporate the original artwork of asylum-seeking children, who were released from detention, as a source for understanding the role of religious belief in their migration journeys. And yet, as the images in this post have demonstrated, detainees themselves produce items of faith, in stark contrast to this exploitive aspect of religious care. For them, religion marks a genuine resource for fostering a sense of cultural belonging in a place designed to racially criminalize them. Religion can also inform acts of protest and resistance against unjust and abusive treatment. Finally, those of us working to give voice to the plights of migrants in immigration detention must take seriously their religious commitments. If not, we allow their religious identities to be controlled by governments and private prison companies.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style)

Cuéllar, G. (2020). Religion in Immigration Detention: Comparing the US and UK. Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2020/01/religion (Accessed [date])

Share: