Adopted and Deported, Orphaned and Detained: The Case of Adam Crapser and the 20,000 Deportable Korean Adoptees in the U.S.

Posted:

Time to read:

Guest post by Hayeon Kim. Hayeon is a graduate of the MSc Migration Studies Program at Wolfson College in 2018. You can read her complete dissertation here. Hayeon’s academic background is in Asian American Studies and American Studies from Northwestern University (Evanston, IL, USA), which inspired her multi-disciplinary approach to race, deportation, and post-war migration. She currently works at Google as an Associate Product Marketing Manager with aspirations to pursue a PhD in the next few years.

In this post, I discuss the peculiar case of Adam Crapser, a Korean adoptee and former Washington State resident who, at age 41, was deported in 2016 from the United States. Despite his adoption papers and U.S. ‘birth’ certificate, Adam was considered a citizen of South Korea, his official country of birth, and moreover a ‘criminal alien’ of the United States. Adam’s case received high media attention and support from human rights activist organizations largely due to its perplexity: how can someone, adopted at the age of three, be deported nearly four decades later?

According to U.S. immigration law, Adam was deported for his convicted offenses, which included burglary when he returned to the Crapser’s home as a homeless teen in search of his own belongings. Adam’s attempt to renew his Green Card triggered a background check for these convictions. Consequently, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement opened deportation proceedings on Adam on January 2015, detained him on February 2016, and deported him 9 months later in November 2016, ultimately separating Adam from his wife and children.

Adam’s case raises questions about citizenship and deportation at-large, and unearths the contradictions of America’s deportation regime. According to the Adoptee Rights Campaign, there are nearly 20,000 Korean adoptees living in the U.S. who lack citizenship records and are thus subject to deportation, and the number is increasing. Based on this trend, no one seems to be ‘safe’ from the mechanisms of deportation, not even adoptees.

Citizenship laws for adoptees have changed over the years, but prior to 2001, automatic citizenship was nonexistent for children adopted by U.S. citizen parents. For example, Adam was adopted in 1979 and given permanent residence status, but it was the responsibility of his adoptive parents to apply for his naturalization and pay the necessary application fees to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (formerly the Immigration and Naturalization Service). Due to the neglect of his adoptive parents, who chose not to apply for his citizenship and periodically withheld his adoption records, Adam was left without citizenship and thus vulnerable to deportation laws.

The citizenship rights, or lack thereof, of Korean adoptees and their subsequent deportability offer an important space to assess the impulses of public sympathy, and to critically analyze how these impulses may align with or belie the social imaginations of the citizen, the alien, the criminal, and the parent. Adam’s case in particular is confounding based on multiple racial, social, and legal notions of citizenship, crime, and deportation: as an East Asian man, he is not readily racialized ‘criminal’ but perhaps as ‘alien’; as an adoptee, he is assumed to be a U.S. citizen; and his deportation no longer affords him the full opportunity to be a parent.

.jpg)

9-minute VICE documentary on Adam Crapser, (TW: suicide, child abuse)

It is necessary to unpack the historical context behind Adam’s case. International adoption of foreign-born children to the U.S. boomed during the combat years of the Korean War (1950-1953), when the resulting 5.8 million refugee population and approximately 100,000 children orphans presented both a political and humanitarian crisis.

On the one hand, a combined anti-communist agenda afforded Asian babies exceptional pathways to migration given the relatively restrictive policies at the time, such as the national origins quota limiting non-Western European immigrants. The ‘rescue’ of ’war orphans’ as a Christian American relief effort, on the other hand, quickly systematized the adoption of Korean babies across the world as a narrative of aid--with no serious debate on the issue of U.S. citizenship. Children born to American citizen soldiers and Korean mothers (or so-assumed based on their biracial identities), dubbed ‘GI babies,’ were considered abandoned, and thus adoptable orphans, rather than as children of American citizens.

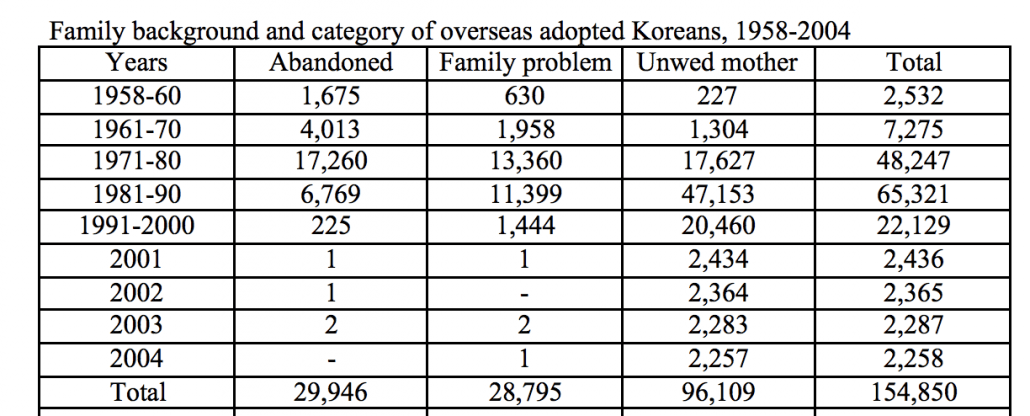

An adoption industry was soon born, in which Korea was the biggest sending country of ‘orphans,’ whereas the U.S. was the biggest receiving country. Orphaned children made up the majority of those adopted in the 1950s and early 1960s, however, as the number of annual adoptions scaled the thousands, adoptions largely encompassed children with living biological mothers. At its peak in 1985, there were 8,837 Korean babies adopted overseas of which an estimated 72% were born from unwed mothers. As adoptees progressed from orphans to ‘paper orphans,’ an adoption industry was born. By the turn of the 21st century, one in every ten Korean American was an adoptee.

The implications of this shift from abandoned, ‘GI babies’ to full-Korean children is crucial to understanding how the logics of adoptability also shaped their deportability. According to U.S. immigration and adoption law, children can only be adopted as ‘orphans.’ As such, ‘orphaning’ the child from the mother(land) became a process intimately tied to assimilation and linear acculturation. Making a child adoptable required that they not only be legally orphans but socially as well. This implied that a ‘clean break’ of ties from the biological parents and birth country meant a child was more assimilable, much to the child’s trauma. Adam remarks:

‘My whole life I was told… that I need to stop worrying about Korea... that I need to quit crying about all these things, about the orphanage, and about my birth mom, because I’m American. That’s what I was told, that I’m American’.

Critical adoption scholarship has provided an urgent and necessary interjection to the dominant narratives of the adoption industry. As more and more scholars, many of them who center adoptee voices or are adoptees themselves, have begun to assess the implications of race, post-war migration, and gender. While the discourse on transnational adoption has evolved extensively over the past few decades, the implications of border criminologies and forced migration remain understudied in this growing field.

Take for instance, the mirroring of adoptability and deportability of Korean adoptees. In many ways, orphanages emerge as rough sketches of the detention centers through which Korean adoptees are ‘housed,’ ‘processed,’ and ‘migrated’ across national borders. Both are institutions of human migration through state-sanctioned laws and actors, moving people across borders as a matter of administrative immigration law or ‘humanitarianism.’ Often, both orphanages and detention centers evoke or involve family separation and potential profit for the state. As Adam expresses in the quote above, orphanages can be forms of erasure for not only his kinship ties, but also his cultural and national identities. Social workers on Adam’s case further expressed Adam’s difficulties in the detention center, where his mental health took a toll as a result of his separation from his family. Adam himself recounts the pain of deportation in his apartment in Seoul, Korea. Detention centers and orphanages are thus institutions of social quarantine and family separation, though more empirical studies can be made to interlace these comparisons.

These institutions implicate a process of orphaning and re-orphaning from the family and nation. The traumas of adoption and deportation, of orphaning and re-orphaning, mirror each other like the endless pit of reflections in which the original subject becomes lost in its reflections. In this case, the national origin of the subject is confused with notions of belonging, and in so doing, the state is relieved of an ‘orphan’ or ‘criminal.’ When the adoptee/deportee is (most likely) a person of color, their notions of belonging are more critically at-risk. Adoptee deportation presents a new parameter for thinking about race and citizenship, and the implications of a growing deportation regime that can justify the deportation of adult adoptees.

Conclusion

Adam Crapser’s case is both ‘exceptional’ and constitutive of the ‘norm’ of the deportation regime. Adam is an exceptional deportee, in that adoptees are typically privileged with U.S. citizenship and thus exempt from deportation. Yet, they are also part and parcel to the norm of deportation, in which crime--however conditioned by the person’s upbringing--cannot relieve even the most ‘American’ of Asian Americans. For a child to be considered completely adoptable and then deportable as an adult are not contradictions of the American immigration system, but similes of the deportation regime.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style)

Kim, H. (2019) Adopted and Deported, Orphaned and Detained: The Case of Adam Crapser and the 20,000 Deportable Korean Adoptees in the U.S.. Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2019/02/adopted-and (Accessed [date])

Share: