Towards a Genealogy of Europe’s Migrant Spaces: A Map-Archive of Border Zones

Posted:

Time to read:

Post by Martina Tazzioli. Martina is Lecturer in Political Geography at Swansea University. She is the author of Spaces of Governmentality. Autonomous Migration and the Arab Uprisings (2015), co-author of Tunisia as a Revolutionised Space of Migration (2016), and co-editor of Foucault and the History of our Present (2015) and Foucault and the Making of Subjects (2016). She is co-founder of the journal Materialifoucaultiani and member of Radical Philosophy editorial board.

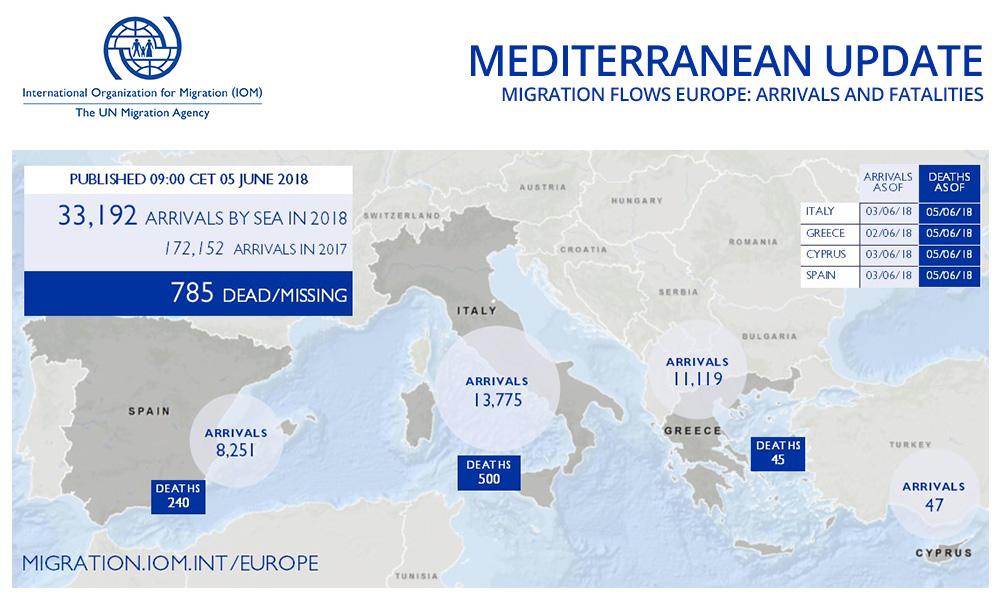

Just as state and media narratives about the so-called refugee crisis reproduce an image of Europe as a homogeneous space where migrants arrive by sea, migration maps produced by international organisations usually depict people as abstract flows invading Europe. Over the last three years, such maps have proliferated alongside cartographic representations of migrant deaths at sea. The IOM Missing Migrant Project and the UNHCR map are among the most updated databases that visualise deaths in the Mediterranean: in both, dots at sea represent the number of recorded deaths. Therefore, as numbers, dots or arrows, migrants do appear on maps as Europe’s intruders.

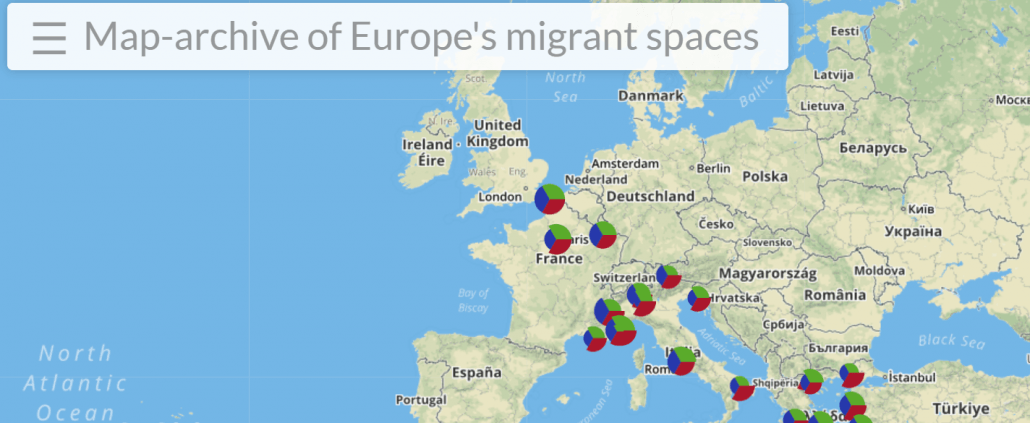

In this post, I discuss a new collective cartographic project, entitled ‘A map-archive of Europe’s migrant spaces’, which seeks to unsettle migration maps which ‘see like a State’ and corroborate the image of migrants invading Europe. In contrast, the map-archive visualises migrant border-zones in Europe as frontiers for migrants in transit. It introduces temporality into cartography by showing how these have changed over time in terms of border enforcements, migrant struggles and humanitarian control. For this reason, it is a map-archive and not just a cartography of migrants’ spaces. This map-archive is the result of a data-collection activity that combines archival research about the history of Europe's border-zones, and interviews with locals, migrants and activists.

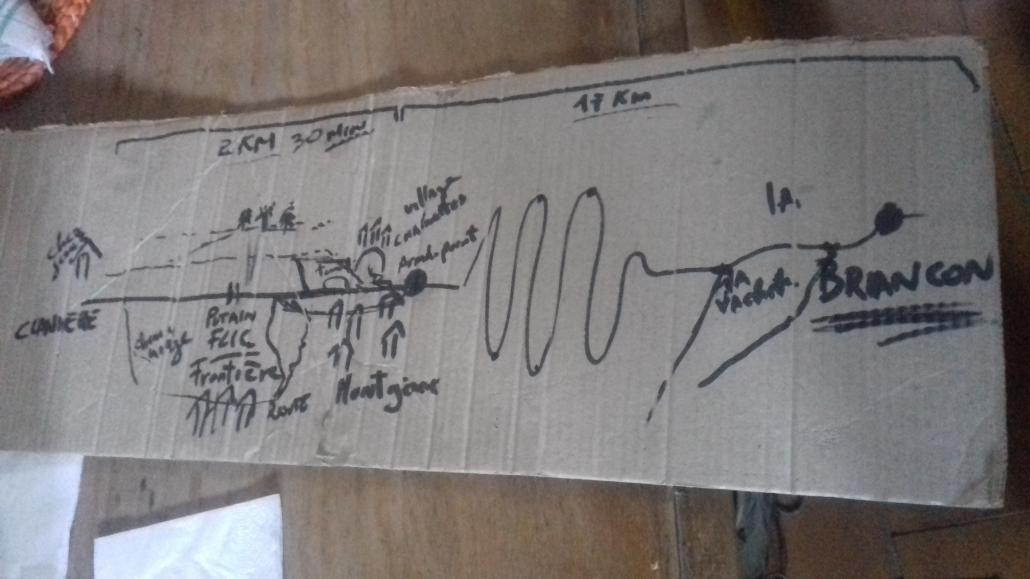

Some of the border-zones that are visualised on the map-archive have a quite long history, while other places have become effective borders for the migrants in transit only recently - for instance, the cities of Como in Italy and Briancon in France; others, like the Greek island of Lesvos, have become the spatial tropes of the refugee crisis. The project, which has been funded by Digital Economy Research Centre ‘Cherish’, is the outcome of a collaborative work made by researchers based in different countries - the UK, Greece, Germany, Italy and the US. In working together, we have asked a series of questions: What are the traces left of the places where migrants remained stranded for a long time, due to the closure of national borders and the suspension of Schengen enforced by some member states? How can we account for migrants’ struggles, their experience of violence at borders and their interactions with humanitarian actors that are not part of the ‘official’ European history? By engaging with these kinds of questions, the map-archive presents the heterogeneity of European space and the variable geometries of migration controls.

Temporality and political memory

An important element of the project is the exploration of how our shared knowledge about migration movements, struggles and solidarity practices have sedimented in Europe over time and how they have been reactivated in the present. Every place and city which is represented on this map-archive - Paris, Calais, Rome, Lesvos, Athens etc. - has been transformed by migrants’ presence.

For instance, at the French-Italian border many locals mobilised in support of migrants in transit, opening temporary shelters, providing food, as well as legal advice. In so doing, their actions may be viewed as part of a longer history of resistances, struggles and solidarity movements. On the Susa Valley, located on the Italian side of the border, for instance, in earlier times, people resisted the German occupation in the 1940s, mobilised against the construction of the motorway in the 1970s and more recently, in the 1990s, communities stood against the high-speed train (NoTav movement). As locals have declared, ‘acting in solidarity with the migrants is for us part of a broader struggle for social justice: we mobilised in the recent past against the high-speed train, today we mobilise for the migrants’.

All the spaces and cities, which are documented on this map-archive, have become frontiers and hostile environments for migrants in transit. Some places are ephemeral and fleeting. The Italian city of Ventimiglia, for instance, at the French-Italian border became a tough frontier for migrants in transit to France in 2011, when the French government suspended the Schengen agreement to obstruct the passage of Tunisian migrants who landed in Lampedusa in 2011 in the aftermath of the Tunisian revolution. In 2015, following some years during which border controls were slightly looser, Ventimiglia became again a difficult border to cross for migrants, since France suspended Schengen for the second time. However, far from being only a checkpoint for migrants in transit, Ventimiglia has been also an important space of collective migrant struggles; the images of migrants on the cliffs holding banners with the motto ‘we are not going back’ circulated widely in 2015.

Migrants unsettling the geopolitical map of Europe

This map-archive project foregrounds another Europe than the one represented on the geopolitical map. Instead of highlighting national frontiers and cities, it visualises places that have been physical borders for migrants in transit and, at the same time as they have also been sites of struggles. In so doing, this map-archive propagates Europe as a space shaped by the presence and struggles of migrants, as well as by border violence and spatial confinement. The geopolitical map of Europe is transformed into Europe’s migrant spaces; that is, the map depicts Europe as it is experienced and shaped by migrants’ presence. Indeed, migrants are subjected to spatial and legal restrictions as well as to human rights violations but at the same time, they also open up spaces for living and for collective struggles.

By giving account of the history of border-zones and keeping memory of migrant solidarity across borders, this project challenges the widespread security gaze on migration: from invaders, intruders and parasites of the welfare system, migrants appear as a constitutive and transformative drive of Europe’s history and of the collective political memory of the European citizens. Through this digital Map-archive, conceived as an open project that we aim to constantly update in the next future, we have pointed to the history of migrant spaces that are not part of Europe’s official archives nor of geopolitical maps. Yet, it is not only a question of spaces but also of what Foucault called ‘subjugated knowledges’ - in this case, the shared knowledges about solidarity practices and struggles - that have contributed to shape the political memory of Europe. Therefore, retracing the history of migrants’ spaces and of the sedimentation of migrants’ practical knowledges, the questions ‘whose Europe?” and ‘which Europe?’ are simultaneously raised from the standpoint of what has contributed to shape the European space without however being part of its ‘official’ history.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style)

Tazzioli, M. (2018) Towards a Genealogy of Europe’s Migrant Spaces: A Map-Archive of Border Zones. Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2018/11/towards-genealogy (Accessed [date]).

Share: