Guest post by Erin Routon. Erin is a Ph.D. candidate in sociocultural anthropology at Cornell University. Her research focuses on legal advocacy in migrant ‘family’ detention facilities in the U.S. Her work addresses questions of care and the management of the complex relationship between the state, for-profit carceral entities, and humanitarian legal advocacy.

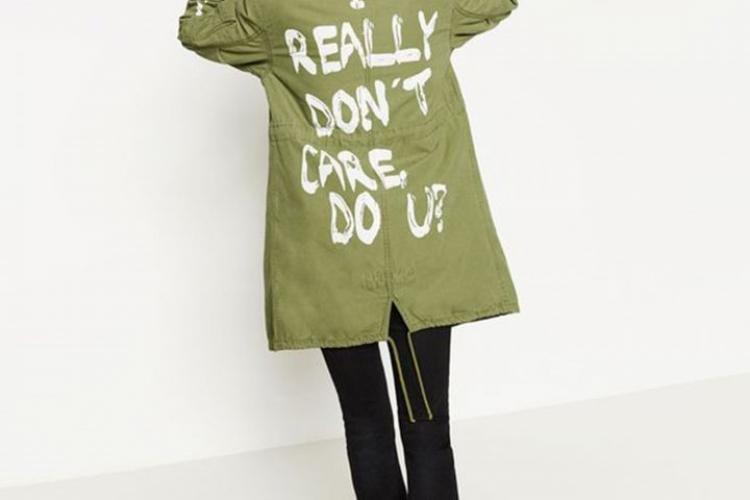

A few months ago, Melania Trump’s ‘flak jacket’ caused quite a stir. The jacket’s inscribed message inspired ever more protest finery, accompanied by vehement public claims of ‘I care’. Although it held the public’s attention for only a passing moment, in this post, I argue that the debate that ensued from this exchange deserves much more attention. Not because it matters what the First Lady wore when she visited the newly developed child detention camps at the border or why she chose to wear the jacket or even what it says about how the current administration feels about these affected families; this is evident in the ways they have implemented new policies and practices at the border, and nothing that the First Lady wears on her tours will change that. Instead of focusing on this, what we should interrogate is the notion of care itself.

It can be quite easy to look at recent measures of the administration and conclude that they simply do not care about migrant families. But what does it mean to care? While possessing rather indefinite boundaries, the concept of care is commonly characterized as having to do with the provision for, maintenance of, or emotional interest in the welfare of another being. What the administration is in fact doing, when either separating family members from one another and detaining them separately or detaining them together, is imposing a different sort of care upon these individuals. Care, in the administration’s language, is more appropriately understood as a project to control bodies, motivated less by empathetic concerns for migrant welfare and more by custodial interests. Yet the ways in which the various entities involved in such practices characterize their roles and activities reflect a vested interest in projecting a more traditional image of care, one that implies that their involvement stems from an interest in the well-being of the migrant, rather than from an interest to control, subjugate, or punish them. These simultaneous but seemingly incommensurate positions toward care are perhaps most evident when the federal government contracts with non-profit entities to fulfill incarcerating roles. For the past few years, family detention in the U.S., which serves to incarcerate asylum-seeking parents with their minor-age children, has been predominantly managed through federal contracts with large private prison companies. Indeed, most immigrant detention centers in the U.S. are managed this way. This approach, however, appeared to shift with the recent contractual involvement with the non-profit Southwest Key Programs.

Although they are just one of many non-profits contracted to ‘care’ for involuntarily incarcerated migrant children seeking asylum, Southwest Key Programs has certainly received the most attention for their involvement in recent developments at the Mexico-U.S. border. They are the organization operating the former Walmart-turned-incarceration camp in Brownsville, Texas, which potentially houses over a thousand migrant boys. In a recent interview with KRGV-TV, the CEO of the organization defensively claimed: ‘We’re not the bad guys. We’re the good guys. We’re the people that are taking these kids, putting them in a shelter, providing the best service that we can for them and reunite with family. And, that’s what this is all about.’ Following this, and in response to the outcry concerning their involvement in such detentions, the organization also released a statement via Twitter asserting that they do not ‘support separating families at the border’ and that they ‘remain committed to providing compassionate care and reunification’ of families.

While contracting with NGO non-profits for such detention appears relatively novel, using the language of care and compassion in justificatory claims for incarceration of asylum-seekers—especially when it comes to the incarceration of migrant youth—is not new. At the two so-called family detention centers in the U.S. where I conducted ethnographic fieldwork—which have served to drastically expand the practice of detaining migrant parents with their children since 2014—the language and imagery of caring is ubiquitous. Colorful children’s drawings line the walls of different buildings, some of which more closely resemble an American elementary school rather than a prison. As a slew of reporters was recently allowed to tour and observe, detainees are confined not to cell-blocks but ‘neighborhoods’, each bestowed with disturbingly childlike names such as ‘Red Parrot’ and ‘Brown Bear’. Prison jumpsuits are replaced with brightly colored t-shirts, jeans, and tennis shoes (the clothes they arrive in are confiscated until they are released).

Officials representing these correctional entities expend great effort to characterize their work in detaining migrant families as caring and compassionate. In an infamous statement during a recent Senate Judiciary Committee hearing concerning the practices of family separation, ICE director Matthew Albence astounded many when he likened these same family detention centers to ‘summer camps’, replete with amenities such as schooling, basketball courts, and dental visits. This tactic of listing amenities was unsurprisingly mimicked by the ICE officer, Michael Sheridan, who led reporters on their tour of that particular facility. Listing facility ‘offerings’ in this way is deployed to bolster the supposed ‘goodness’ of these facilities. These amenities are intended to demonstrate their care, thus serving to justify their continued existence.

In addition to such explicit characterizations deployed to garner public support for their actions, they also use subtler tactics to reify this sort of self-identification. For instance, since the opening of these facilities as family detention centers, they have been known as ‘residential centers’. In fact, both facilities in Texas place that characterization directly in their names: the South Texas Family Residential Center and the Karnes County Residential Center. Inside, prisoners are referred to as ‘residents’ and guards as ‘residential supervisors’. CoreCivic (formerly Corrections Corporations of America), the prison corporation which owns and manages the South Texas facility, describes the center on their website as providing an ‘open, safe environment which offers residential housing as well as education opportunities for women and children who are awaiting their due process before immigration courts.’ In his tour with reporters at this facility, Sheridan stated explicitly, ‘it’s a non-correctional setting. It’s informal.’

And yet, despite these official claims and regardless of the childlike physical qualities that adorn these centers, they are ‘correctional’, in the jargon of incarceration. They are prisons, and their ‘residents’—parents and their young children—are held captive. They are not allowed to leave when they desire, even after they have passed certain requirements that would allow them to continue pursuing legal status while in the U.S., or even if they have decided to accept deportation. Officials and staff at these centers tightly control the behaviors of their prisoners, have been accused of numerous abuses against the detainees, and exhibit deeply antagonistic attitudes and practices toward advocates who, among other things, assist detainees with their legal cases. These legal advocates, with whom I conducted fieldwork, have repeatedly over the years argued the point being made here: regardless of how well these centers might ‘care’ for their prisoners, there is inevitable, unavoidable harm that comes from locking up families and children. There is no justification for arbitrarily imprisoning asylum-seekers.

When carceral facilities are euphemistically characterized as ‘informal’ ‘residential centers’ or even ‘shelters’, facilities borne out of need, rather than federally-manufactured crises, and formed through compassionate interest, care becomes weaponized. For critical scholars of humanitarianism, this is far from revelatory. Many have conducted important fieldwork that demonstrates the ways in which so-called humanitarian efforts have caused more harm than good, some of which is done, like that of Southwest Key, in concert with official state entities (e.g. see here, here and here). These scholars have shown how both humanitarian entities as well as their logics, as often unchallenged or unquestioned in their ‘goodness’, can serve to assist and even reproduce such harmful projects of the state. This is precisely why care cannot be discussed or deployed uncritically. Not unlike the Obama administration, which used the language of care to reason for the construction of family detention facilities in the first place, state officials these days draw up contracts for new detention facilities with the same justification. This will continue.

In her critique on humanitarian ‘regimes of care’, Miriam Ticktin draws our attention to the ways in which immigration in particular has ‘come to be managed…by sentiments and practices of care and compassion’. She further argues that the centrality of such things in the political arena implies that they are seen as ‘solutions to global problems of inequality, exploitation, and discrimination’. Recognizing care’s capacity as a vehicle for exclusionary harm is of vital importance in this moment of manufactured crises involving migrants. It requires critical public attention—in essence, caring about how migrants are cared for—and response to claims of official activities that espouse a caring ethos, perhaps even more so than for those that accompany unabashedly hateful or prejudicial rhetoric. Critically attending to care will perhaps prove more challenging, as it is often easier to recognize the harm that accompanies the latter. But failing to lend a critical lens to the actual activities and vested interests of caregivers or caring entities may unintentionally perpetuate injustice.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style)

Routon, E. (2018) When the State Does Care, Do You?. Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2018/09/when-state-dies (Accessed [date]).

Share: