A Toll Instead of a Barrier: A Case Study of Border Performativity in the French-Spanish Intra-EU Border

Posted:

Time to read:

Guest post by Iker Barbero, Lecturer in Law at the University of the Basque Country. This post is the result of the work carried out within the research project entitled IUSFUNDIE: Fundamental rights and current forms of arrest, detention and expulsion of persons in an administrative irregular situation (Universidad y Sociedad 15/20). A long version of this blog has recently been published in the European Journal of Migration and Law. This is the fourth post of the Border Criminologies’ themed series ‘The Changing Dynamics of Transnational Borders and Boundaries’, organised by Cristina Fernandez Bessa and Giulia Fabini.

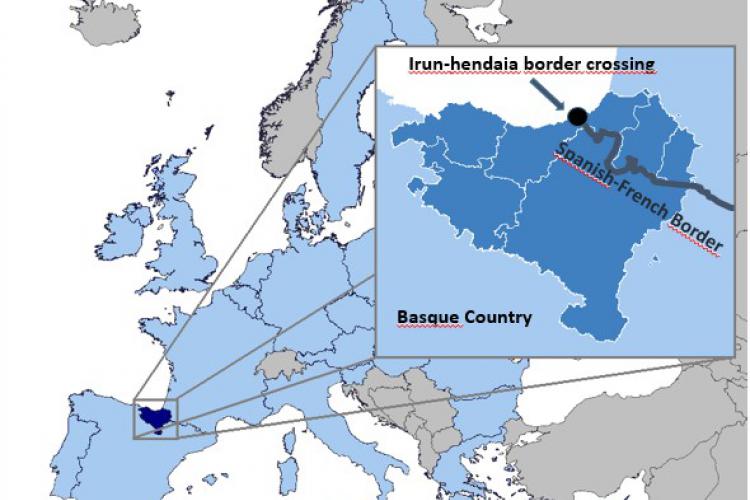

Usually, when discussing borders in Spain, journalists and academics focus on the Southern border of Andalusia, Canary Islands, or the fences of Ceuta and Melilla. However, we know very little about the Northern border: the internal border with France. Analysing and understanding some of the logics of the performativity of control in this specific context will allow us to reflect on the discourses, practices, transformations and dynamism of the borders that are occurring inside the EU and the Schengen territory (and open research lines with the exploration of other internal borders such the French-Italian border, for example).

Drawing on statistical data on the number of foreign nationals, who end up in detention in the Autonomous Region of the Basque Country (Northern Spain), we observed that despite the immigrant population being evenly distributed among the three provinces that integrate the region (Gipuzkoa 8.8%, Bizkaia 8%, Alava 10.5%), the police stations in Gipuzkoa record three times more arrests every year under Foreigners´ Law. More specifically, we noticed that while the number of detainees in the Gipuzkoa province capital (Donostia-San Sebastian) police station is similar to the rest of the main cities (400 annually on average), the local police station in Irun, which is at the border between Spain and France, is much higher, with 800 people detained every year. On top of this, arrests in the Basque Country increase, while in the total in Spain drops 70%.

People who live on both sides and cross the border frequently confirm that it is common to find police controls near the border. Since 2015, France has re-established internal border controls as part of the state of emergency declared after the Paris attacks, further enforced by Macron’s anti-terrorist law of October 2017). In fact, the temporary reintroduction of border control at internal borders on public order and internal security grounds, is predicated by the Schengen Border Code (SBC) (art. 25 et seq).

Although there are three main border-crossing points between France and Spain , in terms of dispositives and technology, two of them can be considered more strained than the third one. The border area of the "Biriatou border crossing" is located around the toll of the A-63 highway road that replaced the old border posts between the two states. However, the location and architecture of this toll is built with cameras, agents' entries, and other surveillance dispositive. Just 100 meters from the Santiago border crossing, and relatively close to the French railway station, where most of the ID checks are carried out on French soil, we find several border control structures. First, the French Police of the Air and Frontiers station; secondly, the French-Spanish Centre for Police Coordination (Blois Convention 1998), open for 24 hours, which employs 64 agents of different police forces in charge of sharing information from the respective databases (SIS, Eurodac, Adexttra, Argos, etc) and the coordination of border operations; and finally, the French Administrative Detention Centre, where according to CIMADE about 70% of detained migrants have been arrested crossing the border.

Under the 2002 Readmission agreement between Spain and France, between 2003 and 2015, more than 300,000 people caught on one side with no authorization to remain were deported to the other side (Source: Spanish Ministry of Interior). More specifically, article 5 states that the police can undertake readmissions ‘without any formality’. Organizations such as CIMADE, SOS Racismo Gipuzkoa, or the Spanish General Council of Lawyers have denounced this procedure drawing on the constitutional and administrative tradition of fundamental rights of both countries, according to which a public action like deportation-readmission need to be accompanied by procedural safeguards, such as access to information and the right to defence and appeal.

In his essay ‘What is a border?’, Balibar states that borders are not any more a classical barrier. Police controls have multiplied and mutated all along the territory as a kaleidoscopic vision. The EU internal borders have never disappeared, as envisioned by the SBC, but have transformed into a police managed model. Indeed, article 23 SBC ( in line with the Article 72 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union), states that the absence of controls at internal borders would not affect the exercise of police powers by the competent authorities of the Member States (in respect of the maintenance of law and order and the safeguarding of internal security), in so far as the exercise of such powers does not have an equivalent effect to border inspections (see European Court of Justice´s Melki and Abdeli Case C-188/10 and Case C-189/10, Adil C-278/12, and the recent Case C-9/16). This 23 SBC provision would enable random inspections to be carried out within the territory and border area without equivalent effect to border inspections. In any case, the controls should be based on general police information and experience on possible threats to public safety and intended, in particular to combat cross-border crime and related to the obligation to carry foreign documents without any necessary prior communication to any EU authority. The Council, in a recent Implementing Decision explicitly encourages Member States to assess whether police checks have the same results as for temporary controls at internal borders, in other words, recommending the use of police checks.

Drawing on the discussion above, similar to other places, the myth of Europe without borders is brought into question. The border is no longer the police cabin and the red and white barrier but any form of selective control, being this a joint police patrol, a coordination centre for a dynamic enforcement of readmissions or a toll. In light of the data, discourses and arguments contained in the soft law documents of the European institutions, it is possible that identity checks, especially in border areas, become more widespread in the future. Following Nancy Wonders´, there is a performative process of invisibilization of the ‘classic border’ while there is a hypervisibility of police checks in border zones and inside the territory with similar objectives but more effective results in social perception. This is a strategic move of the European Union to continue with the border control policy while making EU citizens feel that they can move freely according to their citizenship right/principle. More fieldwork needs to be conducted in different contexts to see whether this situation can lead to a de facto permanent reintroduction of borders, and the end of the borderless Europe project as we knew it.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style)

Barbero, I. (2018) A Toll Instead of a Barrier: A Case Study of Border Performativity in the French-Spanish Intra-EU Border. Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2018/06/toll-instead (Accessed [date]).

Share: