Big Data, Big Promises: Revisiting Migration Statistics in Context of the Datafication of Everything

Posted:

Time to read:

Guest post by Stephan Scheel and Funda Ustek-Spilda. Stephan is currently working as a post-doctoral researcher in the ERC-funded project “Processing Citizenship” at the University of Twente in the Netherlands. Before Stephan was working, together with Funda Ustek-Spilda, as a post-doctoral researcher on the ERC-funded project “ARITHMUS – How Data Make a People” at Goldsmiths, University of London. Stephan’s first research monograph “Autonomy of Migration? Appropriating Mobility within Biometric Border Regimes” is about to be published by Routledge. Funda is currently a Research Officer at the London School of Economics, Department of Media and Communications. She is part of the Horizon 2020 research project, Virt-EU. She also continues her work at ARITHMUS as a Visiting Researcher. Funda is working on her first research monograph “Choosing to be Invisible, Dying to be Visible” on the invisible work of women workers in the informal sector, which will be published by Routledge. This is the final post of Border Criminologies’ themed series ‘Migrant Digitalities and the Politics of Dispersal’, organised by Glenda Garelli and Martina Tazzioli.

We are witnessing the datafication of mobility and migration management across the world. In the context of Europe, programs like Eurosur use satellite images for surveilling the EU’s maritime borders, while the so-called hotspot approach aims to register all newly arriving migrants in biometric databases. Similarly, in the field of asylum, biometric databases are built for purposes of refugee management, while asylum seekers in Greece are distributed cash-cards. These new types and collections of data do not only change border and migration management practices. They also reconfigure how human mobility and migration are known and constituted as intelligible objects of government. The crucial innovation driving this datafication is the digitization of information that was previously stored – if at all – on paper files. This information is now available in a range of databases and can – at least in theory – be searched, exchanged, linked, and analysed with unprecedented scope and efficiency.

As a consequence, ‘Big Data’ are promoted as promising alternative sources for producing more reliable statistics on international migration. Several national statistical institutes (NSIs), international organisations and private actors are currently developing alternative methodologies for the production of migration statistics, for instance, by analysing mobile phone data, geotagged social media data from platforms like Twitter or Facebook or internet searches with particular search terms. Likewise, the UNHCR stresses the (potential) role of social media to inform humanitarian response.

The ‘huge potential of Big Data’ to provide accurate and up-to-date accounts of international migration is promoted. Nevertheless, the promises driving these efforts are just as big as the data they refer to. In this post, we briefly discuss three reasons why it is rather unlikely that Big Data will simply solve the most important known limitations of migration statistics. Each reason is related to a form of politics which, taken together, shape the quantification of migration.

The politics of numbers: policy-driven evidence for evidence-based policy making

The first issue that innovative methodologies are unlikely to solve is the so-called politics of numbers. This politics concerns how institutional interests and agendas of the actors of a particular policy field shape decisions about how migrants are counted and what kind of numbers are ultimately disseminated in the public sphere. For example, according to a tweet by FRONTEX ‘more than 710,000 migrants’ ‘entered

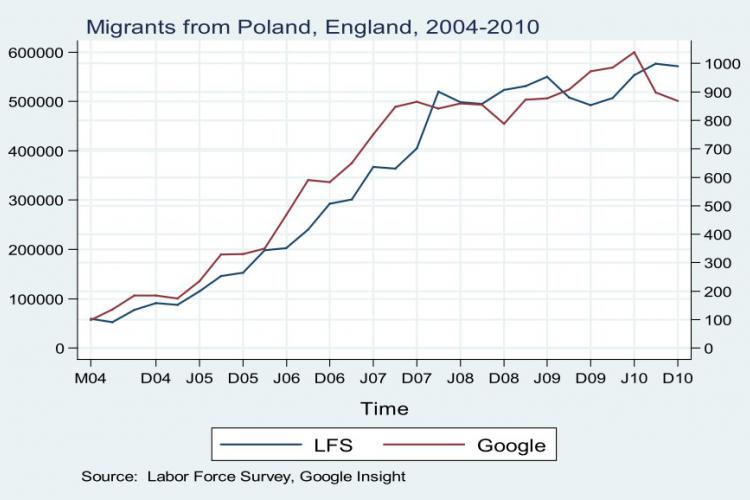

In this context, it is important to note that methodological heterogeneity is not necessarily a bad thing. Rather, statisticians can only assess the reliability and accuracy of any method, as well as its strengths and weaknesses, by comparing it with another method. To illustrate, in England and Wales, the International Passenger Survey (IPS) –the principal method used by the National Office for Statistics (ONS) for the production of migration statistics– became a matter of concern after the last census in 2011. According to the census results, the population size of England and Wales was 464,000 people larger than what had previously been reported by ONS. The latter was based on the so-called ‘cohort component method’, which adjusts the population size of the previous census on an annual basis by recorded births, deaths and net migration figures. An investigation concluded that the ‘largest single cause’ for the divergence was a ‘substantial underestimation’ of immigration from the eight new Eastern European member states by the IPS in the early 2000s. The questionable reliability of ONS migration statistics became a matter of public debate in the context of the promise of then-Prime Minister David Cameron to reduce net-migration to the UK to the ‘tens of thousands each year’, down from an estimated 252,000 in 2010. In light of the inherently probabilistic results of the IPS, a report of the Migration Observatory concludes that ‘efforts to meet the government’s [migration] target lack, for the time being at least, an adequate measure of success.’

The availability of established methodologies for evaluating the results of innovative methods is particularly important in the context of Big Data, since these data sources have usually been generated for different purposes than the production of migration statistics. Consequently, the usage of alternative data sources like mobile phone or Twitter data raise several methodological issues, such as selection bias. Mobile phones and Twitter are, for instance, not used equally by all groups of migrants. This is, why contrary to what their proponents may claim, Big Data-based methods are unlikely to replace established methodologies for migration statistics any time soon. They might rather complement them, thus adding to the already existing methodological heterogeneity.

The politics of (national) distinction: quantifying migration, enacting the nation

The politics of method are also intertwined with a politics of (national) distinction. These politics arise because migration concerns a core issue of national sovereignty: the claimed authority of nation-states to decide on the terms and conditions of entry to and stay within their respective jurisdiction. This claimed prerogative of nation-states results in different migration regimes across nation-states, including different ways of categorising and counting migrants and asylum seekers. Since migration policies are shaped by and are a source of national identity and distinction ‘the harmonization of migration and asylum statistics and policy is controversial as it intervenes in the nation state’s [claimed] sovereign control of who should stay on its territory’, Marianne Takle rightly notes.

The persistence of these differences can be illustrated through the European Statistical System (ESS) that comprises EU member states as well as associated countries. The ESS resembles a ‘hard case’ insofar as it constitutes one of the most advanced, harmonized and robust statistical systems in the world. Principle 14 of the European Statistical Code of Practice stipulates that ‘Statistics are compiled on the basis of common standards with respect to scope, definitions, units and classifications in the different surveys and sources’ to ensure ‘European Statistics are consistent internally, over time and comparable between regions and countries.’

However, our study into the operationalization of otherwise well-established legal categories of asylum-seekers and refugees demonstrates that their conversion into statistical categories entails various moments of adaptation to national contexts. These adaptations, in turn, result in important differences across EU member states. For instance, the harmonised statistical categories for ‘forced migrants’ of the ESS include ‘refugee’ and ‘first time [asylum] applicant’ only, despite the plethora of nationally varying sub-categories. DeStatis, the NSI of Germany, provides an explanatory note on the German asylum regime which distinguishes between asylum seekers whose applications are still pending, have been rejected and have been granted protection status. Each group comprises further sub-categories. These range from migrants who still have to lodge their asylum application or those appealing a decision, to five different types of recognised asylum seekers and various types of rejected asylum seekers, including 154,780 people whose presence in Germany is ‘tolerated’ as they are not deportable.

How asylum seekers and refugees are counted in migration statistics and in the overall population also differ between EU member states. DeStatis counts people from all the aforementioned subcategories in its migration statistics and its population count. Other NSIs in Europe pursue a different policy. For instance, the NSI of Norway, excludes all asylum seekers from its population statistics, as they are not included in the national population register, on which these statistics are based. This is because asylum seekers are not issued personal registration numbers until their application is granted. Eurostat metadata indicates that in many EU countries, only accepted refugees are included in migration and population statistics. The legal limbo asylum seekers find themselves in is reflected in whether and how they are included in migration and population statistics.

Taken together, the three types of politics discussed here demonstrate that Big Data-based methodologies are unlikely to revolutionised migration statistics. Many of the known limitations of migration statistics are related to political issues that cannot be addressed through a technological fix. Rather, the politics of numbers, the politics of method and the politics of national distinction will also shape the development and use of innovative Big Data-based methodologies for migration statistics. So, it is not only the newness of methods per se, but why and how these methods are developed and by whom, that require our attention.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style)

Scheel, S. and Ustek-Spilda, F. (2018) Big Data, Big Promises: Revisiting Migration Statistics in Context of the Datafication of Everything. Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2018/05/big-data-big (Accessed [date]).

Share: