Pushing Migrants Back to Libya, Persecuting Rescue NGOs: The End of the Humanitarian Turn (Part I)

PART I

Posted:

Time to read:

This was not to be the end of the matter, however. Instead, the Italian authorities responded, first, by denying the Open Arms permission to bring the migrants to Italy, which has always been the landing point for NGO vessels acting under the coordination of the Italian MRCC. When the Open Arms was finally allowed to dock in the Sicilian port of Pozzallo, the Italian authorities confiscated the ship. The captain and the head of mission were subsequently charged with aiding ‘illegal immigration’.

This case is unique insofar as it is the first time that: a) The Italian MRCC declares to have transferred SAR coordination to a Libyan counterpart; b) Investigations are opened for acting against the code of conduct that the Italian government imposed on SAR NGOs in the summer of 2017; c) Investigations are opened for not disembarking people in Malta, as requested by the Italian MRCC when the Open Arms transited Maltese waters to evacuate two persons in immediate need of medical care.

On 31 March 2018, the Italian authorities were involved in a similar incident with the Aquarius, a ship operated in partnership by SOS Méditerranée and MSF. After a negotiation with the Libyan Coast Guard, the Aquarius was allowed to take on board only 39 vulnerable and medical cases of the 129 passengers. The rest were forcibly returned to Libya.

In this post, I argue that these incidents are part of a series of developments, which show that Italy is tightening its policy of containment to prevent ‘unwanted’ migrants from reaching European soil, while at the same time waging a war against humanitarian organizations. Through these actions, the government facilitates returns to Libya, which are carried out on Italy’s behalf by the Libyan coast guard and navy. In so doing, Italy is putting an end to its humanitarian turn and moving towards a more exclusionary management of the space of the sea.

The humanitarian turn: Stopping push-backs, launching rescue operations

In February 2012 a landmark judgment of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) found Italy guilty of having returned 24 people from international waters to Libya in 2009, which forced the Italian authorities to review their operations at sea.

In the wake of the Lampedusa shipwreck, which caused the death of 366 people just half a mile off the Italian island on 3 October 2013, Italian authorities launched Mare Nostrum, a large-scale military operation with a twofold, security-humanitarian task. On the one hand, it aimed at protecting borders, capturing smugglers and enhancing police cooperation with the authorities of North African countries, to prevent people from attempting the sea-crossing. On the other hand, it aimed to save lives at sea. Its operational area went as far as the limits of Libyan territorial waters. In August 2014, the Maltese NGO MOAS launched the first non-governmental SAR mission, in cooperation with the Italian authorities, with more NGOs following its example in the following years.

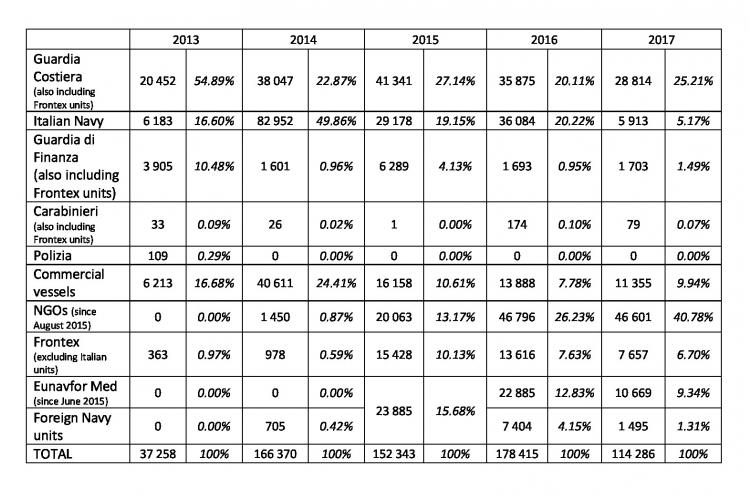

While Italian and EU authorities were trying to strengthen cooperation with Libya in order to prevent people from attempting the sea-crossing, the space of the sea was humanitarianized in such a way as to minimize loss of life and ensure that no one would be returned to Libya from international waters. This picture gradually changed at the end of 2014. While non-governmental SAR efforts increased, governmental engagement in rescuing people decreased. From 2016 onwards, SAR NGOs were also confronted with growing hostility, first, from the Libyan authorities, and then, the Italian ones.

Terminating governmental humanitarian operations

Mare Nostrum was terminated at the end of 2014. The EU not only refused to fund a similar European SAR operation, but also accused the Italian mission of being a pull-factor attracting more migrants and facilitating smuggling organizations. The Italian Navy’s presence in the Central Mediterranean was now limited to the few assets of the operation Mare Sicuro.

At the same time, the EU border agency Frontex launched its new operation Triton, which had no specific SAR task and a very small operational area, up to just 30 miles from Sicily. After a new large-scale shipwreck occurred in April 2015, with an estimated 700 people losing their lives, it was clear that leaving the area south of Lampedusa unattended would only increase the death toll.

While Frontex Triton’s operational area was expanded, and its budget tripled, two state-led humanitarian missions were launched – by Germany and Ireland, respectively – in May. However, both countries later decided to suspend their humanitarian operations and join the EU common security and defence policy mission Eunavfor Med – Sophia that was launched on 22 June 2015. Germany did so as early as 30 June that year, while the redeployment of Irish navy assets from humanitarian to security tasks was enforced only two years later.

Supporting the establishment of a Libyan SAR region and MRCC

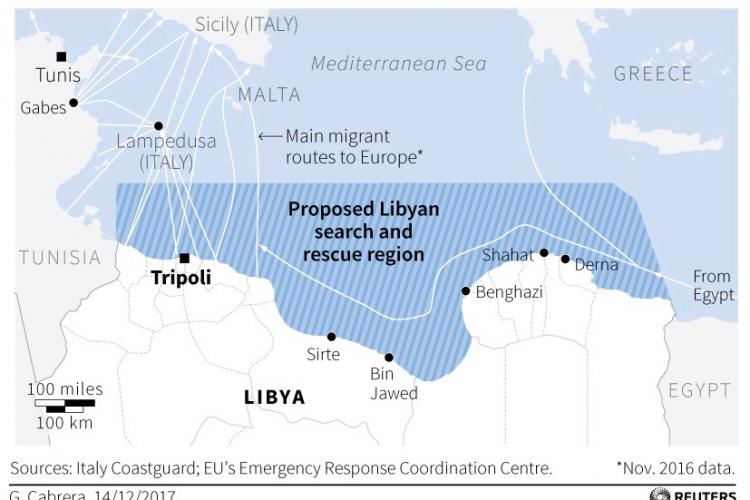

Importantly, Eunavfor Med’s mandate was amended in 2016 to include capacity building and training of the Libyan Coast Guard and Navy. Relevant activities started in October that year and are ongoing. The EU is also committed to assisting Libyan authorities in ‘defining and declaring a Libyan Search and Rescue Region with adequate Standard Operation Procedures’.

The first SAR interventions coordinated by the Libyan authorities in international waters were reportedly carried out as early as September 2017, although no Libyan SAR region officially existed yet, and the EU-funded project led by Italy and aimed at establishing a Libyan MRCC was yet to begin. In fact, these activities were coordinated by an Italian warship from the port of Tripoli. Therefore, Italy could be held accountable for those forced returns as well. Indeed, Italy is also supporting the Libyan Coast Guard and Navy, as well as the Libyan Ministry of Interior, independently from the EU. Following the agreement of 2 February 2017, Italy decided to provide Libyan authorities with ten patrol boats and technical support, and a military mission to Libya was launched in August 2017. The two countries further agreed to establish a joint coordination centre in Tripoli.

Restricting the actual operational area of European and Italian missions

While Eunavfor Med and Frontex Triton had contributed to search and rescue in the area next to Libyan waters in late 2015 and 2016, their assets (as well as those of Mare Sicuro) gradually withdrew from that area between 2016 and 2017, in order to leave the Libyan Coast Guard free to push back migrants, as well as to chase and intimidate NGO vessels.

Such figures suggest that without NGOs, commercial ships would be once again overexposed to distress calls. Consequently, the maritime industry has asked to ‘re-establish [the] legitimate right of NGOs to conduct rescues’. The involvement of commercial ships should be reduced to the minimum not only to relieve them from the heavy financial burden, but also because merchant ships are not equipped, and their crews are not trained, for SAR: therefore, their rescue interventions can easily result in tragedies.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style)

Cuttitta, P. (2018) Pushing Migrants Back to Libya, Persecuting Rescue NGOs: The End of the Humanitarian Turn (Part I). Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2018/04/pushing-migrants (Accessed [date]).

Share: