Guest post by Ridy Wasolua. Ridy is an artist and one of the participants in Gatwick Detainees Welfare Group’s research project, Don’t dump me in a foreign land: Immigration detention and young arrivers. Ridy writes as an expert by experience, having arrived in the UK as a young child, experiencing Operation Nexus and prison, and being detained for a total of more than five years in Immigration Removal Centres in the UK. This is the second post of Border Criminologies’ themed week on 'Young Arrivers in Immigration Detention' organised by Dan Godshaw.

I was born in the DRC. I came here as a young child with my family because we had to flee from war. We got out just in time. Growing up in the UK, I always thought and felt that this was home. I thought I was British.

I made mistakes growing up and I’ve done time in prison. I understand and accept those mistakes and apologise to those who I have hurt. As someone who grew up in the UK and got into trouble, I didn’t understand – no one told me – that I would be treated differently to my friends who had British citizenship. Unlike them, I paid heavily for my mistakes. I paid with my liberty, my childhood, everything I loved. I got sent to immigration detention where I spent more than five years – most of my youth.

Detention is not a place for anyone. It’s not like prison. It’s worse than prison because they treat you very differently. If you can't speak the language officers can take advantage and they can be racist. They swear at you and tell you 'go back to where you come from you African. Go back to your country'.

My country?

My country is the place I was raised in, the place where I went to primary school, secondary school and college – Britain. But the officers look at you like you don't belong and don’t exist. When they look at you like that, you feel like you’re bleeding on the inside. You wonder whether life is worth living.

Detention is scary and frightening. Being locked inside those four walls makes you feel like you are worth nothing. That you are nothing. Some people have been detained so long that they’ve lost contact with their family, friends and everyone they love. People can be moved between different IRCs so often that they get lost in the system and lose all their support networks. As there is no time limit, usually the only way you can get out is if you have a good solicitor. But many people in detention don’t have the money to pay for one and can’t get legal aid. These people need our help urgently.

People can’t take the strain so they take drugs to escape the pain of what they’re going through. I’ve seen men try to hang themselves, set themselves on fire, cut their wrists and smash their heads on walls just to try to stop the pain.

How do you forget such a memory?

The pain of detention doesn’t stop when you get out. It continues to disturb me physically and mentally. My memories of being detained play in my head like horror movies. The ghosts of people held there become like zombies because they don't know where to turn, where to look, who to ask for help. The memory is so raw and emotional. This is happening to human beings. You have to have been released to be able to look back on detention and fully understand that this horror is real, that this exists in Britain today.

Until recently, many people were in the dark about detention. Some still don’t know that this happens. But now, with the help of programmes like BBC Panorama, people in Britain are seeing what happens in detention and now they are starting to wake up. Slowly but surely the truth is coming out. Thank you to everyone who is contributing to the struggle against detention and helping those of us who are going through it. We have to keep fighting for a maximum 28-day time limit to detention.

Another important change that needs to happen is that the authorities must tell people who grew up here without citizenship about the consequences of getting into trouble. They need to let people know that they can be detained and deported to places that feel foreign. This would stop young people from wasting precious years of their lives in detention centres.

Although I was a young man in foreign land I was raised British. Now the government wants to get rid of me. I learnt here that you have to fight for your rights, so I will use the tool of free speech to stand up and speak out – not just for me but to help the younger generation coming behind me. There are many youngsters just like me who are detained right now struggling, not knowing what to do. It is our job to stand up for them and work to bring detention to an end.

We need to communicate to the whole of the UK by using blogs like this and social media; by sharing information so that everyone can see what happens to people who grow up here but were not born in the UK. To see what people like me face when we make mistakes in our lives. People should respect the law, but British law is applied differently to people like me. It treats people who are Black and African unfairly and unjustly.

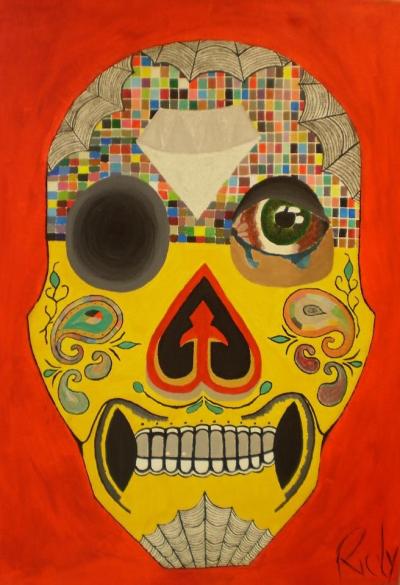

The main thing that keeps me going is my family and friends who support me. People who’ve grown up with me, understand what I’m feeling and what I’m going through. And my art – I can express my pain with paint and this is very important to me. I have to keep on fighting because I belong here like anyone else. No one has the right to tell you where you belong and where you do not belong.

We must pay attention to what’s happening to migrants globally. From the exploitation of migrants in Libya, to their arbitrary detention in the UK. We are humans. We make mistakes. But when humans who do not have citizenship learn from those mistakes and try to make life better, better is not enough.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style)

Wasolua, R. (2018) The Truth about Immigration Detention and Young Arrivers Like Me. Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2018/01/truth-about (Accessed [date]).