In this post, Mary Bosworth, Director of Border Criminologies, describes some of the difficulties she has encountered in her research in immigration detention centres, linking to a new video about such matters, produced by the University of Oxford. Mary tweets @MFBosworth. This is the first post of the Border Criminologies' series on Research and Secondary Trauma.

At the best of times, criminological research is emotionally and ethically challenging; in this subject field we spend our lives thinking about painful issues. As numerous contributors to this blog have shown, conducting research on border controls, is often particularly difficult. Those subject to control are vulnerable, while those wielding power may be resentful or suspicious; their actions can be hard to witness. So, too, the varied expectations and aspirations surrounding our research often feel overwhelming. The relationship between understanding and reform is not a simple one.

Together, such matters, can be deeply affecting for the researcher. Yet, due to the rigors of academia, it is not always easy to admit to anxiety, uncertainty or failure. In any case, our feelings usually pale in comparison with those we are studying, making it easy to sweep them aside as irrelevant.

While our attention, is, rightly, usually trained on our research participants, it has become increasingly apparent that some consideration needs to be given to the process of study itself and its impact on researchers. As the ‘from the field’ blog posts make clear, there are all sorts of aspects of applied research that are confounding or complicated. There is also a range of emotional costs. In inviting researchers to share their experiences, Border Criminologies has sought to support a reflexive discussion of the nature and impact of our work.

In this arena, the Social Science Division at the University of Oxford and the Centre for Criminology, have both been active, devising training and information for researchers and supervisors about secondary trauma. As part of that initiative, I was asked to contribute to a series of videos that are designed for early career researchers. In mine, which can be found here, I speak about some of the practical and emotional difficulties I have faced over the past 8 years of research on British Immigration Removal Centres.

Even today, I find entering detention centres to be unsettling. I sleep poorly the night before. I worry about the purpose of what I do and its impact. The aspirations of research participants can be hard to live up to. My goal is to understand. Yet, those I interview and observe usually hope for more. They want my research to make things better.

The emotional demands of fieldwork can, sometimes, be overwhelming. Over the past eight years I have regularly felt unable to absorb any more pain, suspicion, confusion or hostility. Crying detainees, suspicious staff, and an unwelcome environment take their toll. During the research period and some months thereafter, I have suffered emotional and physical effects from sleeplessness to anxiety and palpitations. It is often difficult to find a way of discussing the research, let alone to analyze my findings, without feeling overwhelmed.

When someone asks me a question about detention, I often answer with too much detail, or, increasingly, without enough. Either I go on and on, or I find myself feeling cynical and wordless. What is the point of rehearsing the same problems yet again?

For long-term projects such as mine, such matters take a particular form. They are also, by now, familiar, if unresolved. To some extent, I’m used to feeling uncomfortable and unsure. These unpleasant emotions are mine to manage, and I accept them as an inescapable part of what I do.

But for doctoral students and postdocs, who might be entering the field for the first time, the strains of research will be novel and may be harder to resolve. It is for that reason, I think, that it is important for more experienced researchers to share their accounts of challenges and how they have overcome them. It is also crucial to consider and acknowledge moments when we have failed to do so.

Emotional trauma will manifest in different ways, depending on our personal histories. Individuals may be particularly affected by certain stories or experiences. It helps, therefore, to reflect on our vulnerabilities before commencing research, and acknowledge them as we go along. For secondary trauma and painful emotions cloud our thought and narrow our horizon. Painful feelings urge us towards simple resolution, desires, that in turn, can lead us to unhelpful or risky actions.

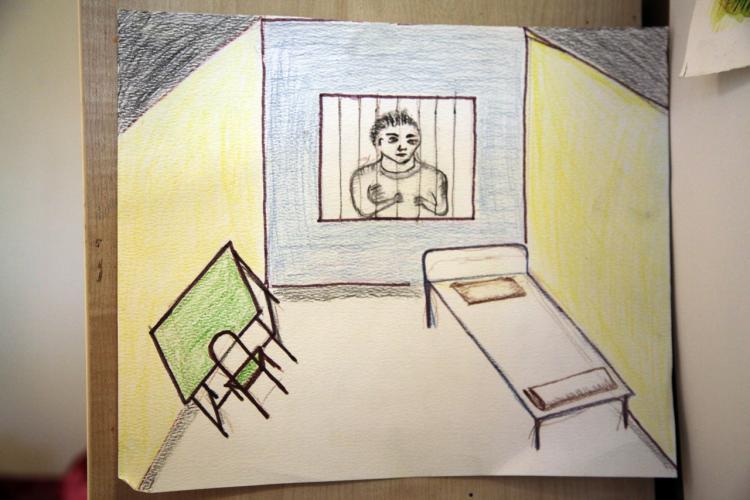

In the video, I was asked to discuss strategies for managing secondary trauma in the field. As you will see, there are some obvious practices that help: creating a support network, talking to peers, reaching out to professional support and building in time to process feelings before commencing analysis. I also began to vary my research methods and approach, trying to find new ways to interact with respondents in more positive and constructive ways. In particular, I experimented with visual methods to engage in the field. This approach provided a way for respondents to express themselves and for me to find out entirely new aspects of their lives and experiences. It was also a constructive way to facilitate the voices from inside these institutions, to provide avenues and ways to amplify their experiences and demands. In turn, Khadija von Zinnenburg Carroll used this material (and added to it), to create a film and images for an exhibition. Together we are putting together an art book with Sternberg Press.

When I began my research in detention I could not have predicted these kinds of visual ‘outputs’ and I feel proud of them. Yet, their effect on debates about and practices of immigration detention remains uncertain. Art may inspire reflection, but will it lead to meaningful change?

In fact, I think we need to manage our expectations about our role and potential impact. It is easy, particularly when conducting fieldwork in hard to access places or with vulnerable people, to feel pressure to make a difference. This pressure emerges from our interactions with those we study as well as from calls for impact within the academy and the research councils. Yet, we need to ask what kind of difference can we make and how best to make it? What is our responsibility? How are we accountable? How can we manage these kinds of expectations?

Despite these difficulties and ambiguities, I do think we have a responsibility to make a difference with our research. Our task is to be critical and thought provoking. How can these institutions justify themselves? How can we hold state power accountable? How does our work slow down or prevent the reproduction of these institutions? Can it? We are in the job of asking questions. We do not necessarily provide the answers. Our work can provide a foundation, evidence, and new ways of thinking. While such matters may be hard to measure, and so fit with some difficulty in the metrics of university management, and while they may also feel weak in comparison to the experiences of research participants, critical thought and reflection are vital in creating a socially just world.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style)

Bosworth, M. (2017) Secondary Trauma and Research. Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2017/10/secondary-trauma (Accessed [date]).