Symbolic Violence in Germany: Defining a Nation through Exclusion and Expulsion

Posted:

Time to read:

Post by Olga Zeveleva, PhD researcher at the Department of Sociology, University of Cambridge. Her research explores intersections of displacement, mobility, and media. Olga is currently working on her PhD dissertation, dedicated to how journalists adapt to regime change, and how different media regimes delineate the borders of nation-states. Olga is on Twitter @OZeveleva. The blog post below is a brief summary of Olga’s latest publication in the journal 'Nationalities Papers.'

In 2014, European media outlets proclaimed a refugee crisis in the EU, and Germany quickly earned a reputation as one of the most ‘welcoming’ countries for asylum seekers ever since. Yet a study I conducted in 2014 at a major German refugee camp reveals that German state discourse leaves no room for asylum seekers or refugees in Germany’s national imaginary. My analysis of the texts, symbols, and spatial organisation of the refugee camp shows that Germany is depicted at this camp as a home to all ethnic Germans, while other groups are excluded from the narrative.

My findings are based on a study conducted in 2014-2015 that included ethnographic observation of border transit camp Friedland, a critical discourse analysis of texts (brochures, the website) relating to the camp, and a total of 15 narrative interviews with co-ethnic repatriate families and asylum seekers living in the camp, employees, residents of the town where the camp is situated, and a two-hour official tour of the camp.

Border Transit Camp Friedland

The German refugee camp Friedland is officially called a ‘border transit camp’ despite its geographic location precisely in the middle of present-day Germany. Established in 1945 by British occupation forces on the border of the British, American and Soviet occupation zones, today the camp hosts about 700 displaced persons from all over the world. The camp has a medical center, a Catholic church, a Protestant church, a day care center, a youth center, a large cafeteria, rooms for the residents of the camp, a museum, as well as offices of the Federal Office of Administration (Bundesverwaltungsamt), which deals with co-ethnic migrants, and the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees. (For a virtual tour of the camp with visual analysis, see my blog post here.)

There are several ways of ending up at this camp today:

- Quota refugees are picked out by the UNHCR and the German government;

- Smugglers may bring undocumented migrants to the camp;

- The legal status of migrants who have resided in Germany may expire and they come to the camp to renew their status;

- A person can come to the camp themselves, without smugglers and without documents;

- The police may send undocumented migrants to the camp;

- Jewish repatriates can claim residency and citizenship in Germany in accordance with post-World-War-II laws;

- Co-ethnic migrants (people who can prove “ethnic German ancestry”) from former Soviet states can immigrate and claim German citizenship, for which co-ethnics apply before their departure to Germany.

The Symbolic Space of the Camp

The symbolic space of the camp, which is comprised of several sculptures and a museum dedicated to the history of the camp, reflects only the background and history of the German co-ethnic migrants, but silences the narratives of all the other groups mentioned in the list above. The camp has no synagogues or mosques, but there are three churches around and in the camp. Discourses that materialise in the transit camp include themes of victimisation of ethnic Germans in the USSR, a discursive link of co-ethnic Germans from the USSR to the experience of German prisoners of war in the USSR, the idea of a ‘return home’ for all ethnic Germans, and the discursive juxtaposition of an unfree East with a free, democratic West.

The museum of the camp includes maps and photographs depicting World War II Prisoners of War (POWs) returning from the Soviet Union to Germany in the 1950s. The sculptures are also dedicated to POW history. The museum, located currently in a former barrack from the 1950s, shows maps of the Soviet Union where POWs and co-ethnic migrants came from before resettling to their ‘home’ in West Germany.

In this context, co-ethnic migrants occupy a peculiar place: they comprise a category of persons admitted to camp Friedland alongside other categories, such as refugees and asylum seekers. But upon further analysis of the narratives of the camp, Russian-Germans actually occupy a symbolic place similar to that of the prisoner of war returnees from the 1950s. Thus, the symbols spread across the camp depict the camp as a place of arrival for Germans; non-ethnic-German incoming migrants are not included in this symbolic narrative. (For more on the museum and sculptures at the camp, see my blog post here).

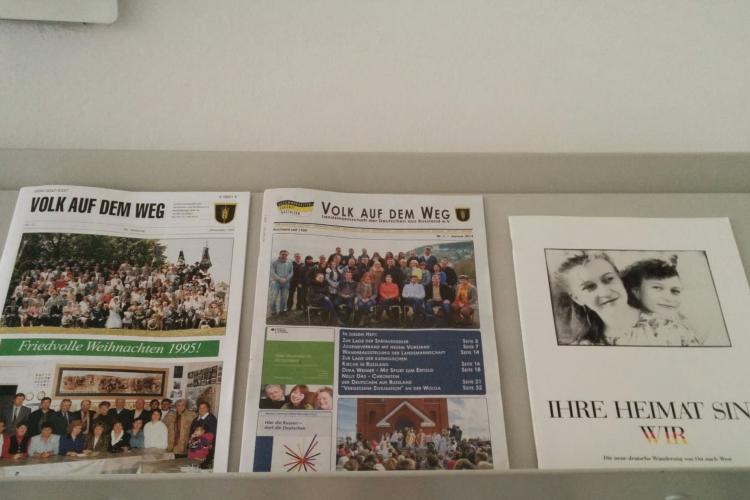

Thus, although the camp has taken on new functions as a place of temporary residence for asylum seekers and refugees, it is the story of the ethnic Germans that comes to the forefront, is depicted on photographs in the museum exhibition, represented in sculptures at the camp, and presented in the reading material provided in waiting rooms on the history of Germany and the history of Friedland camp.

Official Tour of the Camp: The Camp as a ‘Door Between East and West’

During the official tour I took, the camp was presented by the tour guide as a ‘door’ between East and West, subjection and freedom, and this metaphor holds constant both in relation to the times of the Cold War and in relation to the situation today.

In the post-war period and during the division of Germany, the camp stood on the border between all four occupational zones. Pointing to a large map hanging on the wall of the camp’s museum labeled as ‘North Asia – political,’ the guide explained, ‘Almost no flows go east. Compared to the west, very few people go there.’

Speaking of ethnic German repatriates from the former Soviet Union (also referred to as ‘Russian-Germans’) and continuing to point at the map, the tour guide went on to explain the present-day situation: ‘Now, the Russian-Germans come mostly from Kazakhstan and Siberia, and other people come here mostly from Syria, Afghanistan, and Iraq.’ This statement reflects an ever-present East-West divide, in which the construction of ‘the East’ includes Eastern Europe and the former USSR in the past, and ‘Syria, Afghanistan, and Iraq’ in the present. Thus, lines of demarcation between ‘East’ and ‘West’ are discursively redrawn by the tour of the camp, depending on the group of refugees or migrants he was referring to.

During the tour, the guide also alluded to East-West borders within the EU by stating that ‘migrants leave their countries to escape conflict, arrive to Italy or Greece, but it’s not far enough West for them, they want to come here [to Germany].’ Here, Germany is depicted as the most ‘Western’ destination for people fleeing poverty and war. In this construction, we see a multi-step legitimation of Germany as a beacon of freedom and as a destination: Germany is positioned by the guide in a hierarchy above the East and communism, above developing states as sites of conflict from which people flee, and above other countries (Italy and Greece) within Europe. In doing so, the camp retains its symbolic place between East and West across historical epochs, and erases historical responsibility for creating mass displacement.

The Camp as a Space of Classification

The camp functions as a space of classification and hierarchisation both of people and of narratives; the state produces and reproduces these narratives in order to create the discursive boundaries of its membership, and also to create a hierarchy of nonmembers. While co-ethnic migrants arrive as nonmembers, the high likelihood that they will receive residency status and then citizenship status means they are accepted into the structures of the nation-state and recognised as members. The state’s readiness to recognise co-ethnic migrants is manifested in how the camp’s museums and sculptures are organised. By gaining symbolic recognition and recognition by the state as citizens, co-ethnic migrants become part of Germany’s political life.

Other nonmembers of the state are divided into the larger categories of quota refugees and other asylum seekers. While Syrians have a higher chance of receiving asylum, undocumented migrants from other states end up spending much longer periods in the camp, with an even more uncertain outcome. In other words, they have been abandoned by the sovereign; both individually and as an abandoned collective, they will not be integrated into the political life of Germany. Their lives will also be marked by the experiences of detention and deportation; thus, they will be linked to the sovereign power of the German state through being abandoned by the German state.

The camp is the ultimate spatial manifestation of sovereign power. This analysis of Germany’s camp Friedland has shown that the dominant discourse of inclusion is based on ethnic German heritage and victimisation of ethnic Germans in the USSR. In this context, Russian-German co-ethnic migrants are therefore recognised in the symbolic order of the camp and can ultimately gain a place in the political life of the nation. Asylum seekers, by contrast, are not granted symbolic recognition in the camp, their stories are silenced.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style)

Zeveleva, O. (2017) Symbolic Violence in Germany: Defining a Nation through Exclusion and Expulsion. Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2017/09/symbolic-violence (Accessed [date])

Share: