The Circuits of Financial-Humanitarianism in the Greek Migration Laboratory

Posted:

Time to read:

Post by Martina Tazzioli, Lecturer in Political Geography at Swansea University. She is the author of Spaces of Governmentality: Autonomous Migration and the Arab Uprisings (2015), co-author with Glenda Garelli of Tunisia as a Revolutionized Space of Migration (2016), and co-editor of Foucault and the History of Our Present (2015) and Foucault and the Making of Subjects (2016). She is co-founder of the journal Materialifoucaultiani.

Two years after the beginning of what the EU defined as a ‘refugee crisis’, Greece has become the European laboratory of migration policies. The European Commission and the Greek government now portray Greece as a ‘post crisis’ space. According to European agencies, the transition from a period of ‘crisis’ to one of ‘post crisis’ manifests itself in the consistent decline in migrant arrivals. This post examines the effects of containment - whether spatial or temporal - on migrants’ geographies and lives. In so doing, I would like to bring attention to the circuits of migration data, which are the result of data sharing activities and stem from the implementation of financial tools used by humanitarian actors to support asylum seekers in Greece. In particular, I focus here on the Cash Assistance Refugee Programme which has introduced debit cards for asylum seekers. More broadly it examines modes of what I call financial-humanitarianism. This term is used to refer to the increasing financialisation of asylum support activities, i.e. both the implementation of financial tools, such as debit cards, in refugee assistance and monitoring programmes, as well as the opening of financial circuits around refugee management operations. In this regard, Greece represents a case study and a laboratory of experimentation of the first Refugee Cash Assistance programme funded by the EU via ECHO, and coordinated by UNHCR. NGOs that operate inside Greek hotspots and reception centres are in charge of giving and recharging debit cards to asylum seekers on a monthly basis.

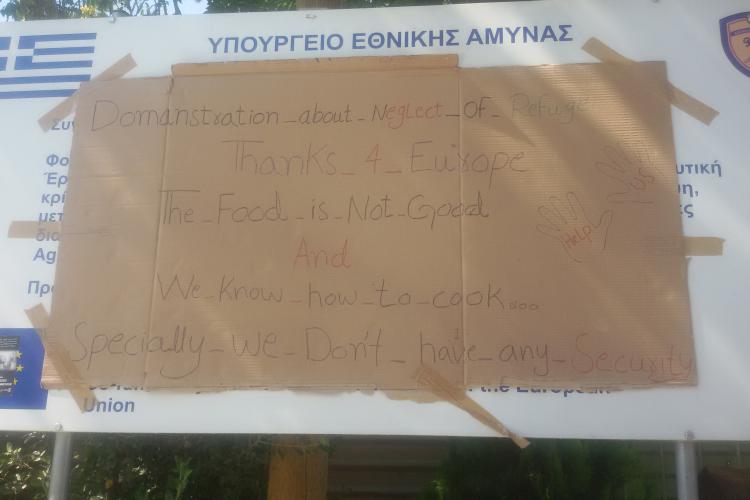

With the implementation of the EU-Turkey Deal Greece has become a space of protracted confinement for migrants. It is also now the starting point of a forced counter-route towards Turkey: about 1800 migrants have been deported to Turkey from the island of Lesvos since the implementation of the EU-Turkey Deal. However, the majority of migrants who arrive in Greece remain stranded on the islands. It can take up to one year before asylum seekers receive a decision. The hotspot of Lesvos - Moria - where there are currently around 3200 men, women and children, represents a neuralgic point of European migration policies and, at the same time, a vantage point; a space from where we can investigate how humanitarian interventions, security measures and processes of value extraction articulate each other.

The invisible circuits of data flows inside the cages of the hotspot

Moria is made of multiple concentric circuits of barbed wire. Its spatial economy extends well beyond its official boundaries, not only because migrants are currently allowed to go in and out, but also as a result of the variety of humanitarian and security actors operate within and outside the camp. I entered Moria hotspot on July 21, with the American NGO Mercy Corps, wearing their jersey for one day, to assist their monthly debit card delivery to asylum seekers. Entering via an NGO is of the few ways to enter Moria, as the government operates under a highly-restricted access policy. Within Moria, sectors A, B and C, full of tents or containers, earmarked for ‘vulnerable subjects’ are immediately visible on my right, beyond two fences of barbed wire and grids. Inside sector-cages A and B there are mainly Syrian families, and sector C holds only women. In front of each of these sectors there are volunteers from the NGO Eurorelief that block access to migrants from other zones of the hotspot; in the name of protection, they also push by force unaccompanied minors inside these sectors. Barbed wire also surrounds the area where the containers of UNHCR and of the European Asylum Support Office (EASO) are located; quite paradoxically, this is a sort of a ‘protection wire’ against migrants, following the riots that took place as a reaction against the indefinite waiting time before their asylum claim is processed and due to the high rejection rate.

Alongside the multiple barbed wire fences, less visible circuits are at play inside Moria and in the other Greek hotspots. These are the circuits of data and information collected during migrants’ identification procedures and asylum applications, as well as those gathered by UNHCR and NGOs to register asylum seekers into the Refugee Cash Assistance Programme. Many of those who have been blocked inside Moria for one year and who have low chances of getting international protection, are at the same time ‘beneficiaries’ of financial-humanitarianism, temporarily included in financial circuits of humanitarian assistance. This form of ‘migration industry’ differs from traditional ways through which private actors make profit running reception centers, extracting value from migrants by capitalising on their protracted presence. Rather, the Cash Assistance Programme enacts peculiar modes of humanitarian intervention in the field of migration management, and transforms asylum seekers into a source of profit for financial actors.

In order to obtain the monthly financial support, asylum seekers need to remain on the Greek islands or, if they are on the mainland, they have to stay in the Greek reception system. This form of humanitarian support via debit cards, in other words, creates modes of spatial entrapment. It also generates new forms of data as the UNHCR collects detailed information about refugees as ‘beneficiaries’ of this financial service and generates surveys concerning migrants’ purchases. In this regard, it is remarkable that the term ‘beneficiary’ has by now replaced the noun ‘refugee’ in the glossary of NGOs that work in Greece. ‘Beneficiaries’ are those people who are registered as asylum seekers and who are still living in a reception facility in Greece. The financial actor involved in the programme is Pre-Paid Financial Services, based in London: they earn 6 euros for every new debit card, and additional fees from UNHCR for every transaction made. In camps where food is provided, each asylum seeker receives 90 euros. In those sites where food is not provided they are given 150 euros. When I entered Moria, Mercy Corps was doing the monthly debit card distribution and recharge, checking that the asylum seekers on the list were still present in the camp.

Financialisation of humanitarianism or of refugee controls?

The expression ‘financial inclusion’, commonly employed by the World Bank and by the World Food Programme in reference to cash-based assistance programmes does not entirely capture the processes of financialisation of refugee support. Instead, temporariness and exclusionary criteria underpin the cash-assistance programme in Greece. In Moria, after the monthly check that Mercy Corps made tent by tent, some of the camp population were excluded from the debit card delivery and recharge, as at the time of writing there were specific eligibility criteria. Those rejected included asylum seekers who had not yet received a legal document by the Greek government.

Those who do not accept the conditions of such a coercive hosting are immediately excluded from the financial circuits of humanitarian support coordinated by UNHCR. As a UNHCR officer told me in Chios, debit cards for asylum seekers in Greece are not considered to be an integration programme but ‘a temporary mechanism for supporting populations in transit’. The selective and temporary inclusion of migrants into financial circuits complements processes of legal destitution: indeed, about 55% of the migrants who claim asylum on Greek islands are either quickly declared inadmissible to the asylum procedure and become deportable to Turkey or are rejected after a protracted wait. At the same time, both inside the hotspots and more broadly across Europe, refugees are increasingly criminalized. Similarly, the concentric layers of barbed wire in Moria and the effects of spatial confinement are combined with immaterial circuits of capitalisation over migrant populations in transit.

In which ways do these financial-humanitarian circuits work at the level of data exchange and data access? Since UNHCR took over the programme in April 2017, all data are stored by UNHCR; the NGOs involved in the debit cards delivery can access some of the information on request. The main worry raised by refugee support groups is that the centralised cash assistance system managed by UNHCR will strengthen data sharing with Greek authorities. In Athens, the Hellenic Red Cross showed me what they can see and the data they can access in real-time, via Pre-paid Financial Services and UNHCR: asylum seekers’ transactions are displayed, as well as the exact locations where the ‘beneficiaries’ took cash from ATM machines or the shops where they used the cards. While access to the cash assistance programme is based on an individual check to see if the person matches the eligibility criteria, UNHCR, which provides the payment, uses the data to produce general surveys about refugees’ purchases, and not to follow people’s internal displacements in the country. In these ways, the financialisation of humanitarian support of asylum seekers is revealed as a mode for temporarily governing migrant populations, while they are within the channels of asylum, sorting between people eligible for the cash assistance and others who are not. Financial-humanitarianism marks a partial shift away from traditional forms of humanitarianism: it shapes asylum seekers as subjects who, on the one hand, have to actively contribute to the government and confinement, and on the other are expected to become ‘autonomous’. These imperatives and effects of subjectivation generated on migrants are combined with disciplinary measures of ‘spatial fixation’. A focus on financial-humanitarianism enables grasping mechanisms of capitalisation over migrants’ movements and presence that go beyond the commodification of migrant labour force.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style)

Tazzioli, M. (2017) The Circuits of Financial-Humanitarianism in the Greek Migration Laboratory. Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2017/09/circuits (Accessed [date]).

Share: