A Critical Look at the Italian Immigration and Asylum Policy: Building ‘Walls of Laws’

Posted:

Time to read:

Post by Francesca Esposito, Doctoral Candidate in Community Psychology, ISPA-University Institute, Lisbon

Another controversial point of the reform concerns migrants’ access to asylum. In order to speed up international protection procedures, the new law establishes only two jurisdictional levels, instead of three, for appealing against an asylum decision, thus reducing asylum seekers’ guarantees and possibilities to be eligible for asylum. Furthermore, specialised courts for assessing these appeals (as well as immigration-related ones) will be established with no obligation to asylum seekers to appear before the judges, allowing for judges’ decision to be based on the video-recording of the applicants’ interviews with the Territorial Commission. As a result, asylum seekers’ right to defense is substantially curtailed, thus limiting their effective access to justice.

Finally, the new Law attributes the role of public officials to practitioners working in reception centers for asylum seekers. That is to say, it appoints the person in charge of the center as responsible for notifying the decision of the Territorial Commission to the asylum seekers housed in the facility. This point has been very much contested by social workers who refuse to play this role of control and repression.

It is also worth noting that some key events forerun this legislative turn. First, a circular, dated December 30, 2016, was issued by the Head of Police emphasizing the importance of the control, identification and removal of foreign nationals. Subsequently, a telegram of the Ministry of the Interior’s Central Directorate for Immigration and Border Police, dated January 26, 2017, urged the Police Headquarters of Rome, Turin, Brindisi and Caltanisetta to carry out ‘targeted services aimed at tracing of Nigerian citizens in illegal position’ in order to detain, and later deport them. At the beginning of February 2017, the Italian government also signed a new memorandum of understanding on cooperation with Libya to curb the flow of migrants to Europe (on the tragic consequences of the implementation of this memorandum see the article of Fulvio Vassallo Paleologo).

These changes mark a regression from the previous Italian immigration policy of 2014 which, among other things, drastically reduced the immigration detention time limit to 90 days (or 30 days in the case of migrants who served a prison sentence of three months or more). So too in the last few years the number of Italian detention centers has been progressively reduced to four (respectively located in Rome, Turin, Caltanissetta, and Brindisi), thus transforming immigration detention into a dispositif for selecting and containing a specific ‘dangerous mobility,’ as Giuseppe Campesi and Giulia Fabini have argued most recently at the Seminar ‘Policing, Migration & National Identity’, held at the University of Warwick).

Against this context, the Minniti-Orlando Decree marks a decisive break from previous positive steps to radically change the face of immigration detention and points to further repression and criminalization of human mobility in Italy. While a dominant narrative of a European humanitarianism toward refugees is produced and upheld by mainstream media, a large part of people on the move are increasingly persecuted and exposed to state violence and, in some cases, even death (see, for example, the work of Rachel Lewis on lesbian migrants). Only few people, the ‘genuine’ refugees, are considered worthy to gain access to ‘Fortress Europe’. In contrast, the lives of others are produced as ‘devalued and ungrievable’ (Butler 2009). The discourse of the ‘humanitarian crisis’, and the framing of refugee migration as a hot spot, also works to reinforce such distinction between deserving and undeserving bodies (see Fernando and Giordano). As Eithne Luibhéid acutely observes, distinctions between people crossing international borders (e.g., refugees, asylum seekers, legal migrants, or undocumented migrants) do not reflect empirically verifiable differences, but are rather imposed by states to legitimise a differential attribution of rights (or the exclusion from their access). According to her, they function as ‘technologies of normalization, discipline, and sanctioned dispossession’.

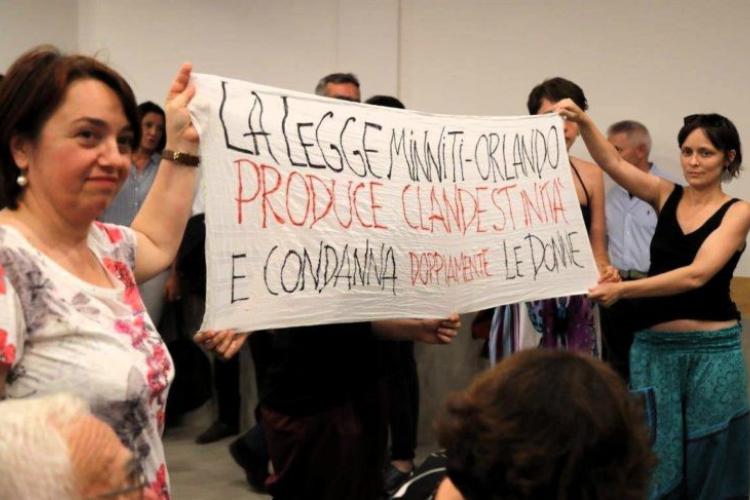

The changes in the Italian immigration policy have been heavily criticized by individuals and migrants’ rights organizations (see for example, ABuonDiritto, ASGI, Associazione Diritti e Frontiere, Casa dei Diritti Sociali, LasciateCIEntrare, Lunaria, Trama di Terre). In particular, the network of social workers against the Minniti-Orlando Decrees was created to resist the repressive mechanisms implemented by this reform. Sits-in, public assemblies and campaigns, and other political initiatives are taking place across Italy. Furthermore, on June 1, ASGI, in the frame of activities undertaken by the Coordination #nodecretominniti, has organized the a conference to critically discuss the new Law and devise strategies to counteract it ( you can see the video in Italian here).

As scholars engaged in the fight for social justice, it is important to do our part by, for example, reminding the public of the detrimental effects that detention has on all people directly or indirectly exposed to it. Such effects not only affect detained migrants, but also service providers working at detention facilities (see for example, Puthoopparambil et al). In the words of Lorenzo Tucco, President of the Association for Juridical Studies on Immigration (ASGI): ‘There are many ways to build walls: with concrete or with laws.’ A common effort for creating a bottom-up push for change is urgent to tear all these walls down.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style)

Esposito, F. (2017) A Critical Look at the Italian Immigration and Asylum Policy: Building ‘Walls of Laws’. Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2017/07/critical-look (Accessed [date])