Guest post by Hanna Musiol, Associate Professor of English at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU). Her research interests include literature, law, curation, and critical pedagogy, with emphasis on storytelling, migration, political ecology, and human rights. She has developed several public humanities and global classroom initiatives in Europe and the US, and she publishes frequently on literary and visual aesthetics and justice. This is the final instalment of Border Criminologies’ themed series on ‘The Memory Politics of Migration at Borderscapes’ organised by Karina Horsti.

Education, Migration, and ‘the Violence of Organized Forgetting’

One of the key functions of education, Henry Giroux reminds us in a recent interview, is to produce not only skilled workers but ‘critical, self-reflective, knowledgeable [global] citizens.’ But, in his view, it is also education—instrumentalized, alienating, and market-driven—that fosters the opposite: the cultural amnesiacs, unaware of their complicated place in history and incapable of ‘mak[ing] moral judgments and act[ing] in a socially inclusive and responsible way.’ The mainstream presence of neofascism and anti-immigrant xenophobia in Europe and elsewhere certainly documents the dangers of such ‘organized forgetting,’ especially of the West’s own contribution to the current refugee crisis, of its own migrant history, its colonial past.

Humanities scholars and educators addressing the violent responses to migrants in Europe, the United States, or elsewhere, are, of course, encouraged to study education and immigrant ‘integration’ (or whatever assimilationist euphemism is mandated at the time) by local and international funding bodies and academic institutions. But not in the “long view” sense. For instance, the 2015’s 1.2 million Euro The Humanities in the Research Area (HERA) bid titled ‘Uses of the Past,” included no funding scheme to include academic institutions in the former European colonies as equal partners examining the European past.) We are often asked to engage in integration projects, but are rarely mandated to examine the failures of public education to help ‘forgetful citizens’ remember; or, asked to tackle the violent and institutionalized memory work “we” engage in our own fields. The way we, too, build, fortify, and police borders. Often ferociously.

Humanities and Storytelling as Civic Practices

New migrants share their life stories all the time. It a mandatory, involuntary part of any legal process. But research and education often require such sharing, too. Few migrants are properly acknowledged or fairly compensated for the narrative labor they perform, despite their narrative labor sustaining both creative/academic, and carceral industries. (Frontex’s staff is to double and its budget is projected to reach €322 million, by 2020, and this does not include individual Schengen’s states’s contributions) Many migrant storytellers in our classrooms and our research projects are exhausted by how their narratives are exploited. By the affective labor we demand in addition to their stories. (Sarah Ahmed in “Melancholic Migrants” and Dina Nayeri, in “The Ungrateful Refugee” talk about the burden of such demands). By how little we hear (not in the ablest sense, of course).

Yet, migrants and refugees have many stories to tell, many narrative styles to express them in, and many motivations to share their experiences on their own terms. As Viet Thanh Nguyen points out, ‘we come wanting to do more than just sell our stories to white audiences. And we come with the desire not just to show, but to tell.’ In order to tell, they find, or imagine, or force into being an audience of listeners. Zakaria Mohamed Ali’s trenchant film about his return to Lampedusa is titled, desperately, To Whom It May Concern, precisely because while the story is always there, the willing, generous listeners are not.

As a scholar of literature and the humanities, I come from beleaguered fields seen as inadequate to address current global problems, when not openly threatened with annihilation. And yet, this field has something to say about migrant storytelling and public memory work. When we are at our best—when we are not building aesthetic white supremacy mausoleums or acting as soulless accountants of aesthetics—we are able to nurture not only the aesthetic but also the civic dimensions of storytelling and enable mutual self-reflection. We are able to avoid the humanitarian model of civic engagement, which disempowers participants and replicates many of the inequalities and biases about givers and takers, producers and consumers of knowledge that it aims to challenge. We can shift attention to not only the voice, the story, or on the migrant as an ‘object’ of research, but also to the ‘forgetful citizen.’ More important, we can create the conditions for listening and reciprocity, Gianluca Gatta reminds us are key. If we succeed, we can make ‘civilizations heal,’ promises Toni Morrison. And this social and political dream has much to do with how ‘we do language,’ how we do the arts.

Of Borders and Travelers

UNHCR figures for forcibly displaced person stand at over 65 million, and this devastating global reality is impossible to ignore. At my home institution, the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), the grassroots response to the migration crisis was immediate, if informal. It involved, among other things, bringing local migrants with academic backgrounds or aspirations into the local academic networks, especially in the public health, medical and humanities fields. (The work was done under the aegis of the ‘NTNU for Refugees,’ although this name is misleading as we work not for but with refugees, in recognition of their expertise, agency, and contributions to our city and research community.)

Many refugee-involving initiatives focus on providing measurable, strategic skills to new migrants, and for a good reason. However, the immeasurable, civic potential of the humanities and the arts, and storytelling, is often overlooked. Of Borders and Travelers aimed to fill that gap. In the fall of 2016, our initiative devoted to storytelling, Anglophone literature, and migration opened its doors to students and refugees from far and wide—from Lofoten, Molde, Oslo, Trondheim in Norway, to the Czech Republic, Germany, Eritrea, Afghanistan, Syria, Iran, Libya, Poland, the US.

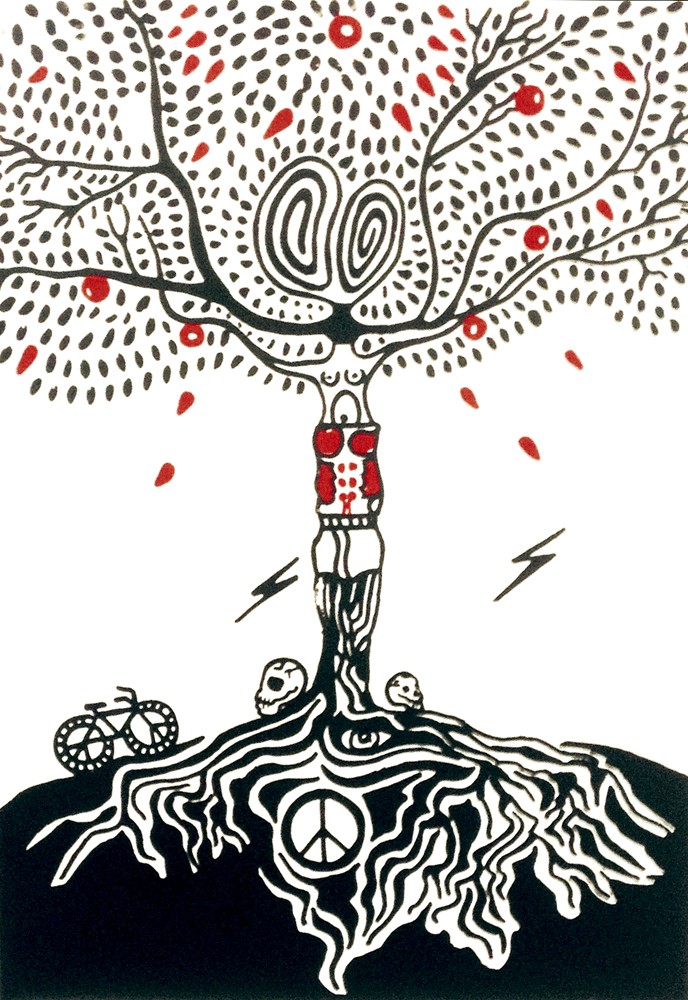

Over the course of several months, we turned to “doing language” and storytelling together. We wrote and read a lot; we listened; we debated ideas in class, in digital spaces, and in public; we collaborated; we drew new cartographies of Trondheim; we translated excerpts from American texts into Norwegian, Arabic, German, Persian, Czech, to find new words, new ways of seeing and saying things in our mother tongues. We wrote poetry, alone and together, and left our mark on the Trondheim poetry scene, too.

In the end, we became better writers, storytellers, and listeners. We also finally understood what Gloria Anzaldúa, Sandro Mezzadra and Brett Nielsen meant when they said that borders are not just walls. They divide, but they also connect and generate. And so we reflected not only on what the national, economic, linguistic, technological, gender, racial, ethnic, environmental, legal, and disciplinary borders are, but more so, on what borders do to us, how they make us into strangers, travelers, tourists, citizens, migrants, fugitives of our global moment and specific local space.

The three months we spent did not magically resolve systemic inequalities among us, but it forced us to see that the barriers of access to education, research, technology, knowledge-making, city space, and, yes, the future, for some of us and not others, have a history and a colonial architecture.

The Right to the Future

Current debates about immigration oscillate between the humanitarian and the carceral discourses, both of which seduce their publics with the promise of integration or homogeneity, with little concern for the genealogies of the marginalization of migrant communities, inside and outside of academia. Moreover, such conversations about migration gesture, often in fear, to the great beyond—the ‘future of the nation’, of Europe, of the global economy, the ‘future’ in the aftermath of migration.

It is time that academics and non-academics together claim the right to coexistence, to our futures being tied to each other, and tied, inseparably, to knowledge, research, and storytelling (Arjun Appadurai). And since the right to such a future is tied not just to the right to tell, but also to an obligation to listen and to remember, academic institutions must both acknowledge their complicity in producing migration history amnesia and engage in collaborative, reciprocal, nearly forensic narrative work across borders of nations and disciplines to redress it. Only then can we be more than barometers of impending human rights crises or mournful historians of disasters.

Acknowledgements: Of Borders and Travelers would not have happened without a small army of volunteers and collaborators: Kristen Over, from Northeastern Illinois University Chicago; Gianluca Gatta, from Archivio delle Memorie Migranti; Hannimari Jokinen, the curator of ort_m [migration memory], Hamburg; Adria Sharman, from Trondheim Kommune; Larry Siems, the editor of Guantánamo Diary; The ICORN Trondheim Refugee Writers at Risk; Sebastian Klein, from The Falstad Human Rights Center; and Olga Lehmann, of Trondheim Poetry Nights. First and foremost, however, credit goes to the NTNU students and Trondheim-based refugee academic guests for the extraordinary intellectual work they accomplished across many borders of our world.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style)

Musiol, H. (2017) On Migration Research, Humanities Education, and Storytelling. Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2017/06/migration (Accessed [date])

Share: