Fractured Childhoods: The Separation of Families by Immigration Detention

Posted:

Time to read:

Guest post by John Hopgood on behalf of Bail for Immigration Detainees (BID). BID is an independent charity that exists to challenge immigration detention in the UK. It works with asylum seekers and migrants, in both prisons and removal centres, to help secure their release. BID not only provides legal advice, information and representation to migrants, but also invests in research, policy, advocacy and strategic litigation. Follow them on Twitter @BIDdetention. This is the seventh instalment of Border Criminologies’ themed series on Current Legal Issues on Migration organised by Ana Aliverti and Celia Rooney.

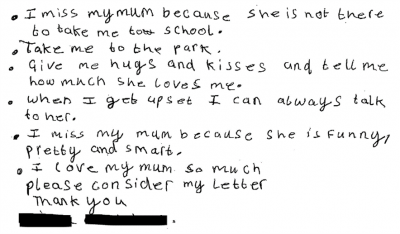

The impact of those decisions on the individuals concerned are, as always, best explained by those directly affected:

'He asks the same questions every night “where is mum gone? where is mum gone?” And

Last autumn, BID produced a piece of research, Rough Justice, which examined the cases of 102 parents who had been separated from their children by detention while facing deportation. These were all people who, prior to the LASPO Act, would have been able to access legal aid. However, in the wake of LASPO few were able to receive any legal advice or representation at all – just 28 (barely a quarter) were able to afford some limited, private legal representation.

Of the 102 parents, 22 (one in five) were deported from the UK without their children. Just six of those parents had legal representation while fighting for the right to remain with their families. Two parents were deported from the UK, wrenched away from their children, because of convictions for false document offences. More than half of the children who had their parents taken from them are British citizens.

During our work and research, we observed a dramatic shift from considering whether deportation would comply with our notion of what is fair and just, to a test that requires that deportation simply not be 'excessively cruel'. We experienced cases in which the Home Office argues that a parent-child bond won't be harmed by deportation because communication via Skype is possible. One client was told by the Home Office that deportation wouldn't breach Article 8 because his family life would be maintained if his British wife and 3 children moved with him to Afghanistan. Yet, such an argument continues to be contrary to official Foreign & Commonwealth Office advice.

The ace in the government's hand, however, is access to justice. Much of the legal aid that was previously available for immigration cases has been cut. This means that few families facing separation because of deportation are able to access any legal advice or representation that would allow them to put forward their case. Even if legal representation is secured, then the Home Office will often ‘certify’ human rights claims. This is the government's euphemistic term for telling those facing deportation that, before there is a chance for a court to decide on their human rights claim, the Home Office has to make a decision on whether their human rights will be breached by being removed from the UK immediately and having their appeal heard from the country to which they have been deported. Amplifying the problem, the Immigration Act 2016 has introduced a ‘deport first, appeal later’ regime, meaning there is no appeal to that decision other than by applying for judicial review – and no assistance to overcome the difficulties of mounting an appeal against deportation from a foreign country with no legal advice or support.

In no other setting would the separation of families by the state for reasons of administrative convenience occur without outrage. Yet, this suffering will continue to be faced by more children and families as the government's assault on access to justice for foreign nationals continues. Up to 1 in 4 people in detention never received legal representation, according to BID’s research, and as few as 1 in 10 people have access to a legal aid solicitor. It is therefore more difficult than ever for vulnerable families to put forward their case.

Removing legal aid for deportation cases involving families has placed an almost insurmountable hurdle in front of many whose greatest wish is simply to be allowed to live with their families. Successive governments may have found removing judicial safeguards and legal aid support straightforward and populist. But the irreversible harm caused by those changes cannot be so easily undone.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style)

Hopgood, J. (2017) Fractured Childhoods: The Separation of Families by Immigration Detention. Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2017/02/fractured (Accessed [date]).

Share: