Child Mobility in the EU’s Refugee Crisis: What Are The Data Gaps And Why Do They Matter?

Posted:

Time to read:

Guest post by Nando Sigona and Rachel Humphris. Nando is Senior Lecturer and Deputy Director of the Institute for Research into Superdiversity, University of Birmingham. Nando is one of the founding editors of Migration Studies, and one of the editors of The Oxford Handbook on Refugee and Forced Migration Studies (Oxford University Press, 2014) and author (with Alice Bloch and Roger Zetter) of Sans Papiers: The Social and Economic Lives of Undocumented Migrants (Pluto Press, 2014). He is on Twitter @nandosigona. Rachel is Research Associate at the Institute for Research into Superdiversity, University of Birmingham and the Centre on Migration Policy and Society, University of Oxford. This is the third installment of Border Criminologies new themed series on Current Legal Issues on Migration organised by Ana Aliverti and Celia Rooney.

Child migration into Europe is diverse and often invisible in data and policy. Legal definitions, bureaucratic practices, rights and entitlements of child migrants vary across European states. While some segments of this population are visible in public debate and datasets, especially unaccompanied asylum seeking children, others are hardly visible, particularly dependent children to asylum seeking parents and undocumented children.

In a recent IOM Global Migration Data Analysis Centre data briefing paper, we review the data sources and statistics collected about child refugees and migrants arriving by sea in the EU, in transit through different European Member States and at destination. We highlight the gaps and limitations in data collection and inconsistencies in terminology, and point to their far-reaching effects for children and young people. This post offers a brief discussion of three aspects touched in the data briefing.

Magnitude, profiles and routes

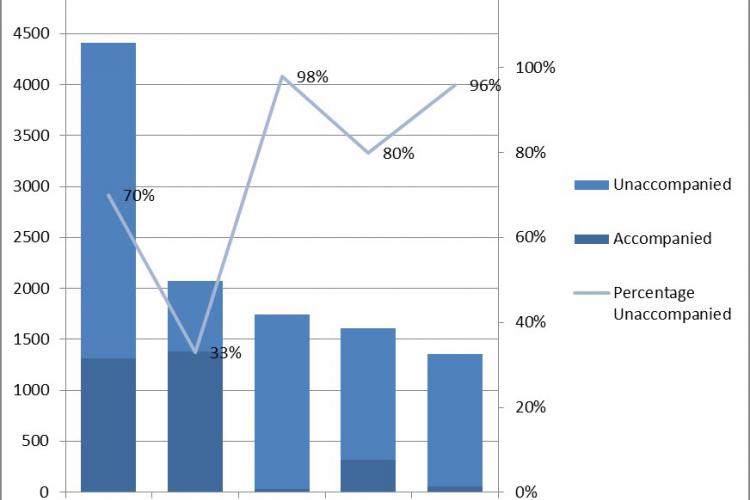

Over one million people reached Italy and Greece by sea in 2015. The large majority of them are young men and women, including 250,000 children. According to UNHCR/IOM data, Greece received 94% of child migrants who arrived by boat, while a far smaller contingent made their way to Italy, roughly 16,500 minors. While only 10% of the child migrants arrived in Greece without parents or guardians according to a UNHCR estimate, in Italy, unaccompanied children were the overwhelming majority (72%) of those who made the dangerous journey across the Mediterranean. A closer look at data on arrivals in Italy and Greece shows remarkable differences in terms of countries of origin across routes, but also reveals variations in terms of travelling arrangements (i.e. accompanied or unaccompanied) within a particular route. The overwhelming majority of minors from Egypt (98%) and Gambia (96%) embarked alone in the treacherous sea crossing from North Africa, whereas young Syrians mostly travelled with a parent or a guardian. In Greece, Syrians and Afghanis are the largest national groups, but while Syrians are more likely to travel with someone responsible for them, this is not the case for Afghan minors.

Often in the media data on sea arrivals and asylum data are conflated, this is potentially misleading for three main reasons: first, not all migrants who arrive by boat apply for asylum, second, not everyone applying for asylum came via boat, third, applications for asylum may happen or be recorded months after arrival in the host country. In relation to asylum seeking minors, EUROSTAT data on asylum in the EU offers an unexpected finding: of the 1.26 million first-time asylum applications lodged in 2015, 365,000 were from applicants who were less than 18 years old. But, perhaps surprisingly given the focus on unaccompanied asylum seeking minors in current debates about child refugees, only 90,000 of minor applicants were recorded as unaccompanied minors.

Data on children in the asylum process are particularly scares for dependent children, number and demographic data of whom are not recorded consistently.

Definitions and data collection

Despite widespread interest in the situation of unaccompanied minors in Europe, we found substantial differences in international, European and national definitions of children travelling alone. While attempts have been made to achieve some coherence at EU level, these have not always been successful and substantial differences persist. For example, there are differences between countries that afford protection mostly on the basis of the condition of separation and age and leave the consideration of the asylum claim as secondary (for example Italy, Spain and France), and countries where the asylum claim is paramount and is initiated at an early stage, therefore quickly dismissing claims made by minors from so-called safe countries (such as in the UK and Norway). Definitions are important because different categories provide different levels of protection in law or in practice.

Inconsistencies also greatly complicate any attempt to understand the significance of the phenomenon comparatively. For those who are recognised as unaccompanied asylum seeking children (UASC) there are significant differences in the way data are collected and identification occurs. For example, in Austria only UASC who receive basic welfare support are recorded. In Croatia only UASC in children’s homes are included in national statistics. In Spain, regional authorities provide data in different formats and therefore they may be incomplete. In the UK each of the four nations differs in the way they collect and publish their statistics.

Missing and double counting

Discrepancies in definitions and data collection can have implications for our understanding of who, where and how many these children are; for the mobility of children between European member states may lead to aggregated numbers of ‘missing’ children on one hand and ‘double counting’ on the other.

Evidence from Becoming Adult, for example, shows that in Italy double counting of unaccompanied minors is common, with some young people being recorded under the care of more than one local authorities at the same time. Duplication is found only much later, if ever, as databases are not joined-up. It may also occur that young people willing to join families or friends in a northern EU state are recorded as unaccompanied at arrival in Italy but then, once they join family members elsewhere in Europe, they lodge an asylum application as ‘accompanied’ minors. This phenomenon may be more widespread that many assume, considering that three quarters of asylum applications from minors in the EU are from accompanied children. So the paradox here is that a child who goes missing in Italy may well reappear in another EU country and be given a different bureaucratic label and, thus, be double counted in EU aggregated data.

Similarly, across EU states there is no consistency in the definition of ‘missing children’. Only half of EU states hold statistics on UASC who went missing or absconded; where statistics are available these are often not comparable or not systematically collected. Only a minority of countries report to have specific legal or procedural regulations on missing migrant children (Austria, Finland, Ireland and Romania). Reporting arrangements for such cases differ substantially. For example, in Estonia these cases are investigated immediately by local police (who issue a search alert). In Denmark they receive instead a lower priority than general cases, while in Belgium there is a fixed ‘no action’ period before the start of police investigations. In England, local authorities have different temporal definitions and safeguarding protocols.

EU data collection has struggled to adjust to the rapid movement of people across EU borders and data or estimates on missing unaccompanied children may not take into consideration children who have ‘reappeared’ elsewhere in Europe.

Mind the data gaps

There are many gaps and inconsistencies in data about children migrating to and through the EU. Although in Greece and Italy data are collected daily on arrival, they are not disaggregated by age or gender. This is also the case in other transit countries and for all dependents in asylum claims. Data on dependent children (including their gender and age) would reveal the hitherto invisible children in Europe who are identified as ‘accompanied’ and is crucial because the majority of migrant and refugee children who reached Europe by sea are accompanied. There is also an absence of data on family reunification and deficiencies in data on detention and return (particularly for those who were unaccompanied minors but then became of age). Moreover, not only are there gaps in data coverage but, as explained above, children are ‘double-counted’. This occurs when disjointed recording mechanisms aggregate, rather than consolidate and synchronise their data.

Early in 2015 EUROPOL denounced the disappearance of 10,000 unaccompanied minors in the EU with a warning that they may be victims of unscrupulous traffickers and subject to exploitation and violence. Despite attempts made to question the validity of the figure and the agenda of the agency in stirring such moral outcry, the ‘killer number’ (a term used by NGO fundraisers) was far too appealing for well-meaning NGOs, advocates and politicians who were genuinely concerned with the plight of this invisible army of potential slaves. The existence of cases of exploitation and trafficking is unquestionable; however, we question the magnitude of the phenomenon and the interpretation provided. The justification given by EUROPOL diverts attention away from the role of EU policy and practices in driving asylum seeking children to go missing and also the legitimate aspirations of, and pressures on refugee and migrant children for example in relation to joining family members elsewhere in Europe and generating income for remittances back home.

We argue that more rigorous scrutiny of data can improve our understanding of the phenomenon of ‘missing’ children and its primary drivers. Crucially, this may help us to refocus our efforts to address the structural causes of ‘missing’ children in order to improve the situation of lone refugee and migrant children.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style)

Sigona, N. and Humpris, R. (2017) Child Mobility in the EU’s Refugee Crisis: What Are The Data Gaps And Why Do They Matter?. Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2017/01/child-mobility-eu (Accessed [date]).

Share: