Fact Check: Did ‘Wir Schaffen Das’ Lead to Uncontrolled Mass Migration?

Posted:

Time to read:

Guest post by Thomas Spijkerboer, Professor of MigrationLaw, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. Thomas is on Twitter @ThomasS_VU.

It is widely assumed that the German ‘decision to suspend Dublin and open the borders,’ epitomized by Angela Merkel’s ‘Wir schaffen das’, led to ‘uncontrolled mass migration’ in the summer and fall of 2015. This belief is not only held by media and politicians, but also by prominent academics like Ruud Koopmans. The empirical claim contained in this belief has two elements: one relating to the ‘suspension of Dublin’, and one relating to the ‘opening of the borders.’

Are these claims correct?

According to the European Asylum Support Office (EASO), for the period 2010-2014 about 10% of the registered asylum applicants in the EU were the subject of Dublin claims, i.e. the country where they had applied for asylum asked another EU member state to accept responsibility for examining the asylum claim. About 2% of all asylum applicants was subsequently physically transferred to another Member State under this scheme (EASO Annual Report 2015). These numbers make clear that the Dublin system was invoked in only a minority of all asylum cases, and actually applied in merely a tiny fraction. It is unlikely that the decision to suspend a set of legal rules which was hardly being applied in the first place has had any significant influence on the number of asylum seekers and refugees in Europe.

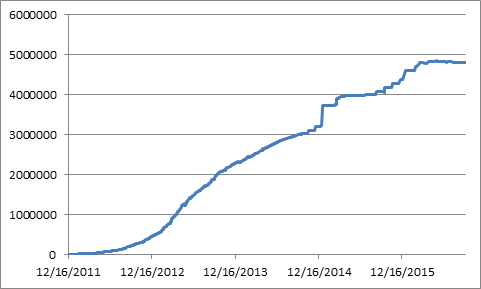

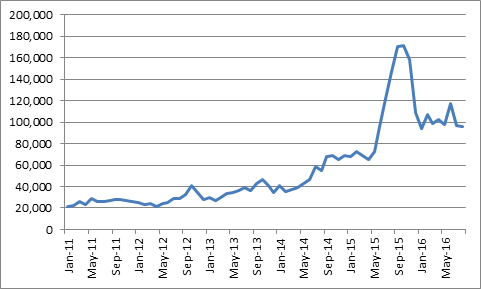

'Wir schaffen das' was used by the German vice-chancellor Sigmar Gabriel on 22 August 2015 and by chancellor Merkel on 31 August 2015 in a speech. The suspension of Dublin (also dubbed as 'the opening of the borders') occurred in the same period, late August 2015. Has this caused people in “the Middle East and far beyond” to decide to travel to Europe? If this were the case, we would see an increase in the number of refugees in September and October of 2015. In this post, I will focus on Syrians, the largest group of refugees coming to Europe. The expected increase could either be an increase in the number of Syrians fleeing their country, inspired by 'Wir schaffen das', or it could be that the number of Syrians traveling to Europe has increased, and I will consider both.

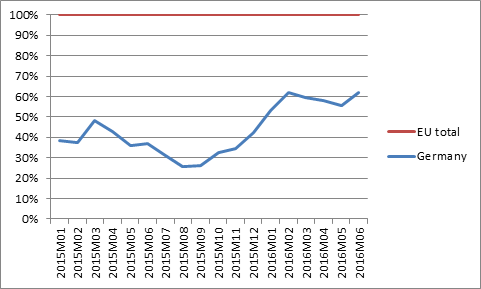

So, the number of Syrian asylum applications had already been increasing sharply for a year. 'Wir schaffen das' and the suspension of Dublin occurred towards the end of this increase, and therefore it is implausible that they caused it. However, could it be that “Wir schaffen das” or the suspension of Dublin, while not influencing the decision of refugees to travel to Europe, did influence the choice of destination country in Europe? Could it be that the relatively large number of people applying for asylum (and not just Syrians) in Germany were influenced by Merkel’s statement? This requires an analysis of the relative distribution of asylum seekers over different European countries through time.

We should, of course, take into account that asylum policies are only one of the potential determinants of the choice (if any) of country of asylum seekers. Existing studies (such as Neumayer, Neumayer, Kuschminder, De Bresser & Siegel) suggest that, apart from physical safety, other important determinants are the presence of family and existing asylum communities, colonial and linguistic links, geographical proximity, as well as perceptions about the economic climate, the levels of xenophobia and the country’s immigration policies.

Summarising:

- It is very unlikely that the decision to suspend Dublin has influenced the number of Syrian asylum seekers and refugees in Europe.

- It is unlikely that the peak of the number of asylum seekers and refugees in Europe was related to 'Wir schaffen das'.

- It is quite possible that “Wir schaffen das” has contributed to asylum seekers choosing Germany instead of other EU Member States as the country of destination.

Are there better explanations for the high number of refugees in Europe in 2015?

Both voluntary and forced migration are complex phenomena, that are influenced by many factors. Policies of potential countries of destination are just one of these factors. Therefore, the idea that one policy measure, let alone one statement can by itself have dramatic effects is extremely implausible to start with. Syrian refugees primarily flee from somewhere. So a primary factor to look at is the development of the violence in Syria (the intensity, its geographical distribution and existence of safe corridors between war zones and the border). Another factor is whether refugees are able to subsist in neighbouring countries. People respond creatively and dynamically to a geopolitical crisis as a whole, not in a linear way to European policy statements.

Elsewhere, I have put forward the hypothesis that the peak in 2015 was a consequence of the de facto prohibition for Syrian refugees of seeking asylum. The most likely understanding of what happened in 2015 is that the combination of the prohibition approach to refugees, the lack of resettlement from Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan and Iraq, and the inability of refugees to receive an acceptable level of subsistence in these countries led to a rapid increase in the demand for the services of smugglers on the Turkey-Greece route. Anecdotal evidence suggests that this initially led to a sharp increase in prices for those taking this route. The resulting increase in profit margin attracted more people to the smuggling business. This then led to a rapid increase in supply, which resulted in falling prices. The lower prices triggered others, such as refugees from Eritrea and Afghanistan, as well as non-refugees, to travel to Europe. This could explain why not only the number of Syrians entering the EU via Turkey has increased sharply, but the number of people from other nationalities as well. The combination of prohibition and not giving refugees a viable alternative in the region has had the opposite of the intended effect, in this context. It led to more migration, not only of Syrians, but also attracted those who might not have otherwise migrated to Europe, to take the eastern Mediterranean route. At present, the data required to test this hypothesis are not available. More than simple statistics are needed, including long-term qualitative research and new statistical data sets that are better geared to investigating policy effects. Nevertheless, the hypothesis I put forward is in line with dominant scholars in the sociology of migration, and it offers a more nuanced explanation of the statistical data rather than the idea that 'Wir schaffen das' or the suspension of Dublin straightforwardly motivated people to move to Europe.

What is the policy relevance of this?

The analysis presented here supports the idea that Angela Merkel has not caused the increase in the number of refugees in Europe, but that, to the contrary, she was responding to a big increase. What Merkel was saying in the summer of 2015 was that, instead of trying to deny that big numbers of refugees needed protection in Europe, it was a better idea to acknowledge this as a given fact. The thrust of her argument was: let us not try to close the border, but let us do everything to provide shelter to people who need it.

However, if one government is perceived as being more generous than other European governments, this may well influence the distribution of asylum seekers within the European Union. What does this imply? Should governments try to influence the perception which asylum seekers have of their country? If they succeed in coming across as tough on refugees, and if they all do so with equal success, this leads to a distribution which is similar to the status quo ante, but only with tougher rhetoric (and possibly with tougher policies). Competing on (actual or perceived) toughness does not significantly diminish the total number of people getting to Europe, but only affects the distribution of asylum seekers over EU member states. If policy makers want to prevent an uneven distribution of asylum seekers over EU member states, it seems more plausible to opt for effective harmonization of European asylum policies, something that has miserably failed so far. This would create a level playing field and would eliminate some factors contributing to the uneven distribution of asylum seekers over EU member states.

In this blog post, I have put forward an alternative hypothesis to explain the rise of the number of refugees in Europe in 2015. As I indicated, empirical research to test this hypothesis fully is absent, but the hypothesis makes suggestions about the increase of the number of refugees in a more complex way, beyond the idea that 'Wir schaffen das' or the suspension of Dublin were the cause. If my hypothesis is even partly correct, this implies that under certain conditions European policies may completely backfire and lead to more migration and more border deaths, instead of less. This, in turn, would require a fundamental reconsideration of the premises underlying European asylum law and policy.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

Share: