Locked In

This is the second installment of the themed series on Border Criminologies network members. The series aims to present our members’ ongoing research, recent publications, new course modules they might be developing, grants and awards, partnerships and collaborations, and questions they have been considering or struggling with.

Posted:

Time to read:

Research update by Alpa Parmar, Border Criminologies, Centre for Criminology, University of Oxford. Follow her on Twitter @AlpaParmar11.

In January this year, I was delighted to officially join the Border Criminologies team as my research developed in new directions through working on a project to understand how migration is policed in the UK. My previous work has considered policing and race and the criminalization of British Asian men. Migratory histories, ethnic identities, notions of belonging, and processes of exclusion and racism have thus always been part of my work and this project allows me to see how these issues are recast in the contemporary climate of mass migration. The University of Oxford John Fell Fund award enables me to work with Mary Bosworth on how mass mobility has influenced ordinary policing practices and how this impacts the relationship between the immigration service and the police in the UK.

The project is well under way and I’ve been spending time each week in police custody suites and on the beat with officers. Through hours of ethnographic observation and interviews with police custody sergeants, police officers, and custody detention officers, I’m seeing how people who have been arrested are treated in police custody and the additional processes, agencies, and procedures involved when the suspect is from (or thought to be from) a foreign national background. When a person is being booked into police custody, they are asked their nationality and it’s often, though not always, at this point that detailed checks are carried out about their immigration status. The person’s right to remain is checked and their removability is ascertained (with the command control unit and immigration compliance and enforcement teams). Interpreters are called if necessary, fingerprints are taken and checked against the Home Office database, and details of any previous contact with the Home Office are established. Photographs and samples of DNA (from a mouth swab or hair) can also be taken and stored on the police database. The police can hold a person for up to 24 hours before they have to be charged with a crime or released.

The cases of the migrants in the lorry and the criminal damage are so different, yet both are the focus of our policing migration project. As the custody sergeant told me:

foreign nationality is one extra part of the procedure. It’s not that we have a different process for foreign nationals, it’s just that we might see different things…and we have to look out for those things. The vulnerabilities are manifold and vary greatly, but it all comes under the label of foreign national.

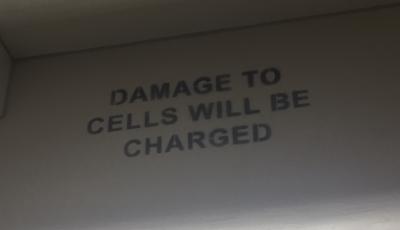

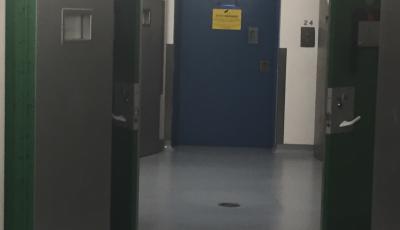

As you’d imagine, police custody suites are usually dark, tight spaces and can vary vastly in terms of how many cells are in a suite and how many people can be held at any one time. When I arrive at a suite I can usually see how many people are being held by looking at the board and also by glancing down the cell corridors, noting the pairs of shoes placed outside the cells.

Alongside the police custody observations, I’ve been working with the criminal records office (ACRO) to understand how they operate with the police to obtain and provide information about foreign national suspects’ offending histories from the EU and non-EU countries. For example, the ‘Ask ERIC’ app is increasingly used by police forces to access criminal conviction information for people within the EU. Over the next few weeks I will spend time with each of the hubs at ACRO to understand how previous conviction histories are requested when a person is arrested and the various agreements being set up to make this process of information exchange smoother.

Following the observations at ACRO, the next phase of the research will involve shadowing case workers at the immigration service to understand how information is used and processed at their end. For example, how is information about new and previous convictions used to progress the case for someone who has an insecure immigration status? How are systems of information amongst the police and immigration brought work together on a case? And how are decisions to remove someone based on criminal convictions made?

The multiple angles of this research project make it challenging to understand how the different parts connect to each other and I hope that this will become clearer in time. In the meantime, I see how this research brings together old and new strands of my work: the policing of minority ethnic groups and their migratory histories have always formed a lens of analysis for me, as has the blurred distinctions between victims and offenders when unpacking the relationship between race and criminal justice. Seeing who is brought into police custody and the reasons for arrest has also revealed the sharp reality of new forms of racism towards migrants that are often beneath the surface of everyday order and daily interactions.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style)

Parmar, A. (2016) Locked In. Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2016/06/locked (Accessed [date]).

Share: