Asylum Archive: An Archive of Asylum and Direct Provision in Ireland

Posted:

Time to read:

Guest post by Vukasin Nedeljkovic, creator of Asylum Archive. From April 2007 to November 2009, Vukasin was housed in a Direct Provision Centre while seeking asylum. Asylum Archive grew from that experience: ‘I kept myself intact by capturing and communicating with the environment through photographs and videos. This creative process helped me to overcome confinement and incarceration.’ In this post, and through Asylum Archive, Vukasin examines the notion of direct provision, constructing a theoretical framework on the issues of power, authority, detention, and supervision.

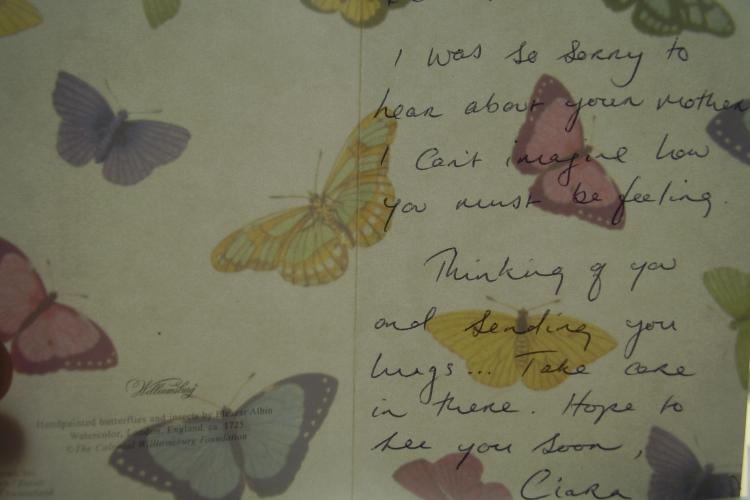

I receive a postcard covered with the butterflies; the yellow butterflies with the white dots, the purple butterflies with the white dots, the green butterflies with the green dots and the blue butterflies. I look at the postcard. I hold the postcard. The tears roll over my cheeks on to the postcard.

My window is divided in half. There are yellow marks at the both sides of the window. The mark on the left side of the window is bigger and wider then the mark on the right side of the window. There are fields in a distance. They seem too far away. I can't see the greenness of the fields. It rains almost every day. The fields are becoming greener every minute. I want to see the fields with my tired, sleepless eyes. I am afraid to leave the room 24. I am not able to smell the fields. It is just round a corner. There are walls and barriers on the way.

I bite my nails; the drops of blood roll over my finger. I look at my hand; in my room, on the piece of paper, I write down ‘lost’ using the same blood. On a different piece of paper I also write ‘lonely.’ The sun is coming through the dirt of my window. I see the children playing outside. I smell the chicken nuggets and chips. It is dinnertime soon. – Nedeljkovic, 2008

The direct provision scheme was introduced in Ireland in November 1999 to accommodate asylum seekers in state designated accommodation centres. There were more than 120 centres located across the country, some of which include former convents, army barracks, hotels, and holiday homes. Most of the centres are situated outside cities on the periphery of society. The decision to house asylum seekers in remote state centres significantly reduces their possibilities for integration, leaving them to dwell in a ghettoized environment.

Asylum seekers live in overcrowded, unhygienic conditions, where families with children are often forced to share small rooms. The management controls their food intake, their movements, the supply of bed linen, and cleaning materials exerting their authority, power, and control. According to Ronit Lentin, direct provision centres are ‘holding camps’ and ‘sites of deportability’ which ‘construct their inmates as deportable subjects, ready to be deported any time.’ Similarly, the Free Legal Advice Centre states that these privately owned centres, administered by the Government of Ireland, constitute a ‘direct provision industry,’ which makes a profit on the backs of asylum seekers.

Asylum Archive originally started as a coping mechanism while I was in the process of seeking asylum in Ireland. It’s directly concerned with the realities and traumatic lives of asylum seekers. Its main objective is to collaborate with asylum seekers, artists, academics, and civil society activists, amongst others, with a view to create an interactive documentary cross-platform online resource, which critically brings forward accounts of exile, displacement, trauma, and memory.

Asylum Archive is not a singular art project that stands ‘outside of society’ engaged in an internal conversation; rather, it’s a platform open for dialogue and discussion inclusive to individuals that have experienced a sense of sociological/geographical displacement, memory loss, trauma, and violence. It has an essential visual, informative, and educational perspective and is accessible, through its online presence, to any future researchers and scholars who may wish to undertake a study about the conditions of asylum seekers in Ireland.

My practice-based doctoral project at the Centre for Transcultural Research and Media Practice, Dublin Institute of Technology, examines a particular time in recent Irish history―from the inception of the direct provision dispersal system in 1999 to the present day―while at the same time the Asylum Archive project creates a repository of asylum experiences and artefacts.

Issues of governance, exile, displacement, trauma, and memory have preoccupied many scholars and are helping me make sense of my experiences and the direct provision scheme. For instance, the photographer and theorist Allan Sekula describes Bentham’s idea of the panopticon where ‘the principle of supervision takes on an explicit industrial capitalist character: his prisons were to function as profit-making establishments, based on the private contracting-out of convict labour. Sekula observes that for Foucault, ‘panopticism’ provides the central metaphor for modern disciplinary power based on isolation, individuation, and. He also contends that ‘

This project also considers questions of memory in the asylum-seeking process. As Arjun Appadurai has astutely argued:

Memory, for migrants, is almost always the memory of loss. But since most migrants have been pushed out of the sites of official/national memory in their original homes, there is some anxiety surrounding the status of what is lost, since the memory of the journey to a new place, the memory of one’s own life and family world in the old place, and official memory about the nation one has left have to be recombined in a new location.

Direct Provision Centres are the primary focus of my research. The ‘new’ category of institutions that are ‘deprived of singular identity or relations’ where the undefined incarceration is the only existence. The identity of asylum seekers is unknown; ‘their identity is reduced to having no known identity.’ Direct provision centres are ‘non-places’ where asylum seekers establish their new identity through the process of negotiating belonging in a current locality.

Direct Provision Centres are disciplinary and exclusionary forms of spatial and social closure that separate and conceal asylum seekers from mainstream society and ultimately prevent their long term integration or inclusion. They are, as Steve Loyal argues drawing on Erving Goffman, ‘total institutions, forcing houses for changing persons, each is a natural experiment on what can it be done to the self,.’ The Direct Provision Scheme is a continuation of the history of confinement in Ireland through borstals, laundries, prisons, mother and baby homes, and lunatic asylums. When the Irish state initiated the Direct Provision Scheme, it deliberately constructed a space where institutional racism could be readily instantiated, explicitly through, for example, the threat of transfer to a different accommodation Centre or for deportation.

In this sense, Direct Provision Centres are, in the words of Emmanuel Levinas, ‘the absence of everything... the place where the bottom has dropped out of everything, an atmospheric density, a plenitude of the void, or the murmur of silence.’

However, in my view, Direct Provision Centres cannot be exclusively perceived as sites of incarceration, social exclusion, or extreme poverty. More importantly, they can be seen to constitute oppositional formations of collectivity and resistance against State policy in which different nationalities and ethnic groups exist and persist despite the very conditions of confinement created by the state.

Key questions remain. First, how can asylum seekers be less than strangers in a profit-making direct provision establishment? Second, can ‘slow activism’ be of value in Irish debates about transforming direct provision, where the activist potential for change is, according to Wallace Heim, ‘listened’ into existence? And third, what will it take for society to understand the inequalities that are perpetuated through the operation of direct provision? These are questions I continue to examine in my doctoral research and through the Asylum Archive.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style):

Nedeljkovic, V. (2016) Asylum Archive: An Archive of Asylum and Direct Provision in Ireland. Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2016/04/asylum-archive (Accessed [date]).

Share: