Guest post by Olga Zeveleva, PhD student at the Department of Sociology at the University of Cambridge.

The German refugee camp Friedland is officially called a ‘border transit camp’ despite its geographic location precisely in the middle of present-day Germany. Established in 1945 by British forces on the border of the British, American, and Soviet occupation zones, today the camp hosts about 700 displaced persons from 11 countries across the world. In March 2016, the new official camp museum will open its doors to the public, offering exhibitions on the history of the camp and its evolution over time.

As we await its opening, I invite you on a virtual tour of the camp through this post. Over the past few years, thousands of asylum seekers have spent time here, some as long as 18 months, waiting for decisions on their legal status in Germany. The space is laden with powerful historical images of German World War II POWs, ethnic German return migrants, and migrant flows from an imagined ‘East’ to ‘West.’ The photo series presented here shows how some narratives are represented at camp Friedland, while others are silenced, creating a powerful symbolic hierarchy of members and nonmembers of the German state. It is the result of fieldwork conducted in Germany in 2014-2015 for a study on migration to Germany.

Border transit camp Friedland is located geographically in the very ‘middle’ of Germany near the city of Goettingen. The camp was first set up by British allied forces in 1945 to accommodate people who had been displaced during World War II (including German prisoners of war returning from Eastern Europe). A cow barn was originally the centre of this small-scale refugee camp. Situated on a major railway route, the camp was on the border between the American, British, and Soviet occupation zones.

Today, this railway, shown in image 1, remains one of Germany’s busiest transportation routes. Officials can thus send undocumented migrants to camp Friedland from many railway connections. Additionally, undocumented migrants who wish to file for asylum or repatriates arriving from abroad can easily get to the camp using public transportation.

Image 2 shows Friedland train station, now home to the new Friedland museum that’s scheduled to open in March 2016.

Like most other camps in Europe, Friedland is located in a rural area, a demonstratively peripheral site (shown in image 3). The people at the camp are thus not integrated into any form of public life or urban life in Germany. This is a deliberately anti-urban structure, depicting a sterile image of order; to capture this kind of spatial organization, Richard Sennnett has used the metaphor ‘urban condom’ to describe the camp.

The official camp tour guide emphasizes the fact that the structure around the perimeter of the camp ‘is not a fence,’ and the buildings where people at the camp live ‘are not barracks’ (see image 4, a photograph of the camp). The tour guide’s emphasis on the ‘non-fence’ demonstrates an acute awareness of the connotations of a ‘camp’ and stresses that people who stay there are actually free to leave and to be mobile. In reality, however, the bureaucratic barriers in place in the German and EU asylum systems render the asylum seeker immobilized; even if s/he is to leave the camp, s/he will be brought back by the authorities until a decision on the asylum seeker’s legal status is reached. Moreover, without an asylum decision, an asylum seeker has no access to the welfare services of any EU state.

Image 5 shows a camp building in the foreground (living quarters for asylum seekers) and private homes of the town of Friedland in the background. The camp tour guide stressed that the people living at the camp are intergrated into the greater town. The town itself, however, is home to very few businesses―in 2014, for instance, there was one supermarket, one hotel, one guest house, and one cafeteria―and few institutions exist that aren’t related to the camp. According to both a local cafeteria owner and employees of the camp, many of the town’s residents work at the camp. Sennett’s ‘urban condom’ metaphor underscores the lack of integration of asylum seekers, refugees, and repatriates at the camp into either the public life or the economic life in Germany. The people at the camp receive pocket money from the state every week and donations from charities. In this way, they are isolated from the market economy.

Many of the most prominent buildings of the camp are comprised of waiting rooms (pictured in images 6 and 7), where asylum seekers fill out paperwork, wait for interviews, and wait for decisions on their status. Social time is suspended at the camp and replaced by rhythms of waiting.

An asylum seeker from Eritrea told me that she keeps track of how many days she’s been at the camp by counting the meal stamps she’s received from Friedland’s cafeteria. The meal stamps are attached to temporary ID cards given to each new arrival. There are seven meals on a given card and each time a person receives a meal, the card is stamped next to the date. Since no one knows how long they will stay at the camp, the asylum seeker receives a new card at the beginning of each new week, which is stapled atop the old page. The use of the food stamp pages as a calendar reveals the connection this woman has made between satisfying her basic needs and telling time―a process governed by the rhythms of the camp’s schedule.

Image 7 depicts a separate waiting room for co-ethnic German return migrants, or ‘Russian-Germans.’ Germany practices a policy of repatriation of ethnic Germans from the former Soviet Union. Russian-Germans can apply for repatriation, come to Germany, and claim German citizenship on the basis of their ethnic backgrounds as descendants of migrants from Germanic lands in the 18th century. All co-ethnic repatriates currently arrive in camp Friedland before finalizing their status in Germany.

The Russian-Germans live in the same buildings as asylum seekers and refugees from all other countries at camp Friedland. Several of my interviews with Russian-Germans revealed a degree of animosity towards other groups of asylum seekers and refugees at the camp. The prominent discourse of ‘ethnic German belonging’ at the camp, and in magazines, newspapers, and brochures distributed to Russian-Germans upon their arrival (see image 6), creates a strong sense of Germany as a destination for all those with German roots in is a construction often cited by Russian-Germans themselves. ‘They’re not from here, they’re completely different and have a different culture,’ one Russian-German from Kazakhstan told me at camp Friedland. This ‘Germany is for Germans’ rhetoric used by some Russian-Germans is structured partly by the German government’s discourses on repatriation and the importance of co-ethnic migration for German society.

Often, large families of eight to thirteen Russian-Germans arrive at the camp together, spanning three generations. The entire family typically stays in the same room until the officials assign them to a German region and provide them with transportation to their new place of residence. In many cases, one of the older relatives acts as the main repatriation applicant, while others in the group apply as accompanying family members. The accompanying family members can also claim German citizenship, but depending on the degree of their relation to ethnic Germans, they may receive fewer social benefits, smaller pensions, or a longer waiting period for naturalization.

Image 8 shows a recreation of a camp building from the late 1940s to 1950s. Today it houses Friedland’s museum. The exhibition will be moved to the train station building for the opening of the new museum in March 2016.

The inside of the current Friedland museum can be seen on image 9. The museum features a recreation of a Friedland medical office from the 1950s (seen at the end of the room), photographs of German World War II POW returnees, and a map of the former Soviet Union indicating where co-ethnic German repatriates lived before repatriating to Germany.

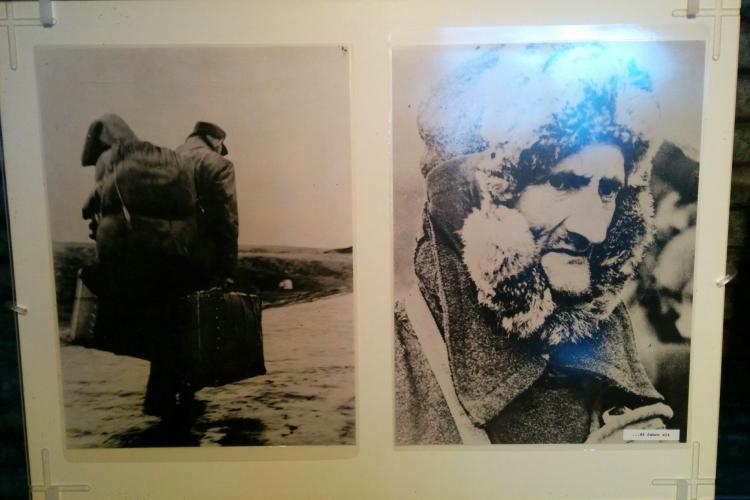

These photographs hang on the walls of the current Friedland museum. They show German POWs who were returned from the former Soviet Union. The man on the right in image 10 was 40 years old when his photo was taken.

In his book Homecomings: Returning POWs and the Legacies of Defeat in Postwar Germany, historian Frank Biess claims that returning POWs were depicted in West Germany as victims of Soviet captivity, and such practices of post-war POW commemoration erased boundaries between victims, bystanders, and war criminals.

This sculpture stands outside one of the churches of the camp. It’s a figure of a German POW returning to Germany from the former Soviet Union. More than 500,000 women who had worked in various capacities in the German Wehrmacht during World War II (mostly as members of auxilary forces and Red Cross nurses) were captured by the Red Army and then returned to Germany with the other POWs. Biess notes that conferences of German POW returnees (Heimkehrer conferences) were almost exclusively male events, validating male experiences of captivity. The sculpture in image 11 and the photographs of POWs from Friedland’s museum (images 9 and 10) are all representations of military masculinity.

The sculpture in image 12 is a symbol of World War II POWs returning from the former Soviet Union. When new groups of POWs arrived at the camp in the 1950s, the bell would chime. The bell has been dismounted from its base several times and taken to conferences of World Ward II POW returnees throughout Germany. Today, the bell no longer chimes when new arrivals come to Friedland.

This sculpture from image 13 stands outside the cafeteria and near the main entrance to the camp. It’s designed to look like a natural part of the camp’s landscape, growing straight out of the cobblestones. It depicts a rugged and uninviting East in the shape of one water basin, out of which water flows along a long bronze path westward, into another water basin symbolizing the West. The water depicts the flow of people from ‘East’ to ‘West.’ This symbolism underscores the image of a passive and anonymous ‘mass’ of people coming to the (free) West from an unfree East.

This photograph shows the ‘Eastern’ side of the sculpture symbolizing the ‘East-to-West’ flows of people. Behind it and to the right is one of the three churches surrounding the camp. There is no synagogue or mosque in Friedland.

We can read the camp as a space where the German state classifies both people and narratives, creating the discursive boundaries of membership within and to the state. While co-ethnic migrants and German POW returnees take symbolic center-stage at the camp, other groups of people who live there have no spaces of representation at Friedland. Alternatively, the images of ethnic German migrants shown here can be interpreted as a reminder that Germans too experienced a history of displacement that they now share with other groups coming through the camp today. German society has, in many ways, remained a post-war society, and camp Friedland is a space where the German state is continuously coming to terms with ever-changing questions of identity, memory, and belonging.

This photo essay focuses on state-produced representations but private practices of commemoration and appropriation of camp spaces among asylum seekers and refugees merit closer attention, both in this camp and in others. By addressing both the state’s constructions and individual practices, we will be able to better understand modern topologies of displacement.

Acknowledgements: This project was made possible by a research grant from the National Research University Higher School of Economics in 2014-2015. I also thank Niklas Radenbach for his help and support during my fieldwork; Lena Inowlocki and Ursula Apitzsch for their helpful comments during the colloquium on biographical sociology at the Goethe University in Frankfurt; and Sergei Medvedev and Andrey Makarychev for their 2015 Escapes from Modernity winter school in Estonia on ‘The State and the Body’ where I shared my preliminary results.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style):

Zeveleva, O. (2016) Symbolic Borders in Detention Spaces: Inside a German Refugee Camp. Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2016/02/symbolic-borders (Accessed [date]).

Share: