Guest post by David Sausdal, PhD research fellow, Department of Criminology, Stockholm University. David holds an MSc in social anthropology from the University of Copenhagen. By combining his anthropological training with a criminological curiosity, he ethnographically explores everyday issues of transnational crime and the policing thereof.

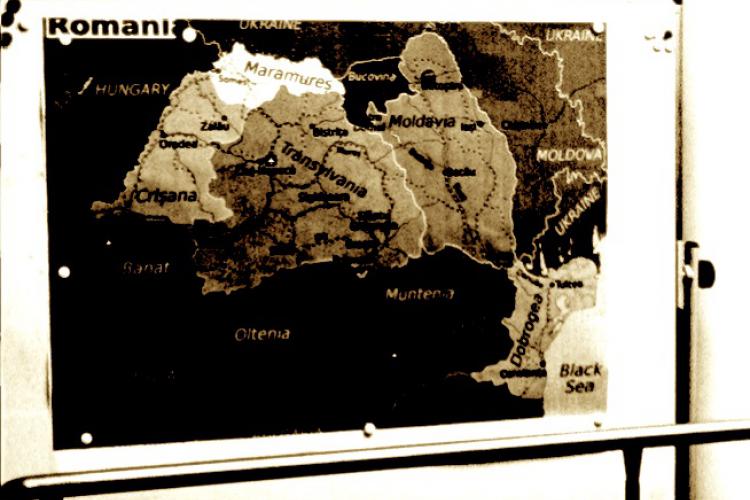

In this somewhat speculative post I reflect on what I term ‘the right to crime.’ Based on an extensive observational study of the Danish police’s apprehensions of non-citizen burglars and pickpockets from countries such as Poland, Romania, Morocco, and Chile, I demonstrate how the police’s perceptions of these criminal foreigners not only speak of the police’s condemnation, but also of what the police, so to speak, ‘condone’ as the right kind of crime/criminal.

This point can be shown through the following account by a detective from a North of Copenhagen-based Police Task Force who complained about the crimes committed by a group of Romanian burglars:

The thing is… why do they have to come here to our country, into our homes, and steal our stuff? I know that they are not much to steal back where they come from, but, hey, that is how it should be.

With only insignificant variations, his complaint was echoed by many of his colleagues. Thus, what united the detectives was not, as one might presume, their general disapproval of the criminals and their criminal ways. To them, minor, non-violent property crime is most often a not-to-be-upset-about, run-of-the-mill occurrence. Instead, their disapproval was related to the place the criminals stole from: ‘why don’t the just steal something at home instead of coming here?’ they would wonder.

This example reveals that amidst the police there exists an idea about the right kind of spatial relationship between the criminal and his/her loot. However, it doesn’t necessarily mean that the police believe that a Danish person stealing in Denmark isn’t a criminal; it merely hints at how in the minds of the police there is a spatial relation that perceives and designates certain acts of crime as being more acceptable than others. Put differently, both criminal acts will be condemned by the letters of law, yet the crime committed in the wrong place will also be morally condemned.

To consider why it’s wrong for a Romanian and ‘right’ for a Dane to steal things in Denmark, analytical aid might be found in the work of Simmel. In his essay ‘The Stranger,’ Simmel argues that all human relations are organised by socio-spatial notions of nearness or remoteness. This entails, mundanely put, that the way we relate to the people we meet, including the expectations and reactions we have to their behaviour (criminals included), is based on whether we believe them to be belonging to the same social world as us or not. Here, belonging is not a dialectal concept but a difference in degree.

Using ‘the stranger’ as exemplary of a person who doesn’t belong to his/her social world, Simmel wrote:

The stranger is by nature no ‘owner of soil’, soil not only in the physical, but also in the figurative sense of a life-substance which is fixed… in an ideal point of the social environment.

By appreciating this, we get closer to understanding the extra condemnation voiced by the Danish detectives. To them, the stranger, this criminal foreigner, is not understood as ‘owner of Danish soil’; that is, he is not understood as belonging to ‘the social environment’ which the loot he steals is part of. By negation, the criminal citizen, by being understood as part of the social environment, is in theory owner of Danish soil, not of course by property law but by a Simmelian sociological law of social belonging. Put differently, and admittedly quirkily, the belongings the criminal citizen steals somewhat belongs to him before he steals them given how he is thought to belong to the same social environment as the belongings belong to. In short, there exists a prior ‘right’ to crime when the thief is believed to belong to the same social world as the thing he steals.

That this sociospatial ‘right’ to crime exists became even clearer to me when observing how the detectives of a Copenhagen Police Task Force dealt with the Danish pickpockets they encountered. Dressed in civilian clothing, two detectives and I were patrolling Copenhagen Central Station looking for pickpockets. Suddenly, we heard shouts coming from the ticket machines area. We ran over and saw a man fleeing the scene with two women pursuing him. One of the detectives ran after the man and stopped him just before he reached the exit. The pickpocket had stolen a wallet. The detective gave the woman her wallet back and then had a chat with the pickpocket. Having talked to and fined him, the detective turned to me and said:

I know him. He is one of ours. He has problems, you know. Like, what else is he to do? He needs money and this is where he can get it. This is where he lives.

In the eyes of these detectives, this desperate Danish pickpocket, alongside others, didn’t have any other options but to steal from his immediate surroundings. It is not that the detectives did not think that a foreign pickpocket did not also have problems. As mentioned above, their issue with the criminal foreigner was more related to how he did not steal from his immediate surroundings. The Danish pickpocket, however, is thought to belong to the social environment surrounding Copenhagen Central Station. ‘He is one of ours,’ as they would say, encircling him socially, thus giving him, if not the right to crime, then greater police tolerance. A gift of forbearance not as easily donned to the foreigner.

Bearing this in mind, and reframing the discussion in the criminological vocabulary of the late Nils Christie, what this example hints at is that a criminal can be an ‘ideal criminal’ an idealisation, which, if following the aforementioned train of thought, is, amongst other things, connected to ideas about social belonging. The question to be further explored, then, is how social belonging is defined/felt by different social groups? What are people’s ‘imagined communities’ and how does these affect their views on different crime/criminals?

Although there isn’t space here to explore the otherwise interesting question as to what kind of ideas of social belonging makes crime more right or more wrong, what can nevertheless be argued is that the ideal act of stealing (and maybe crime in general?) demands an idea about a prior social connection between the criminal and his loot. In other words, a total stranger may not steal your stuff. The question remains, of course, how closely connected the criminal should be as to obtain the perfect social relation wherefrom his criminal act becomes ‘only’ a criminal and not a moral offence? For, where the stranger is too far away, it’s just as easily thinkable that one can be too close. If, for instance, a close family member or friend steals from you it would in many cases be seen as not just illegal but also immoral. Thus, the right to crime may demand that one is a perfect stranger: not too far away, nor too close.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style):

Sausdal, D. (2016) The Right to Crime: A Search for the Ideal Criminal. Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2016/03/right-crime (Accessed [date]).

Share: